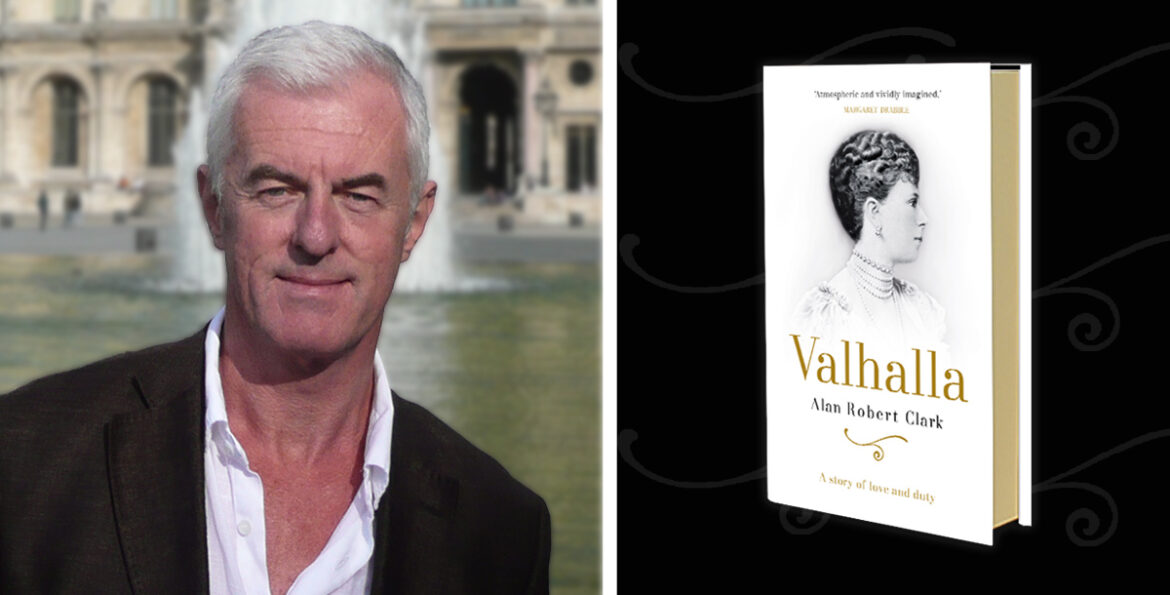

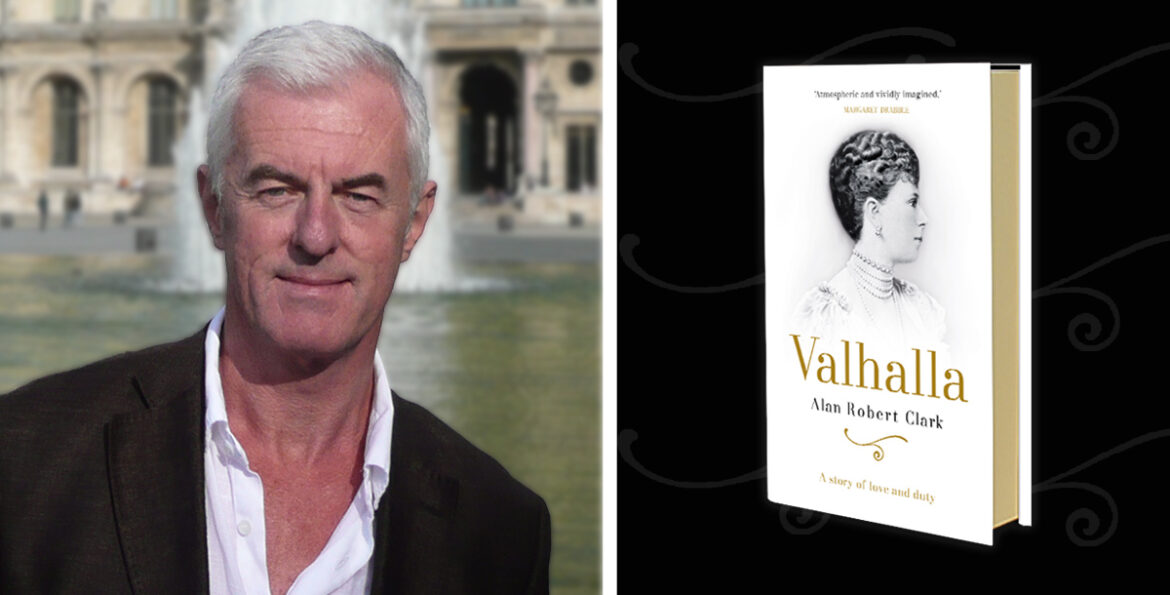

Alan Robert Clark: Writing Queen Mary

It might seem an odd thing for a leftie, Guardian-reading republican to do. I’d just written one historical novel about a member of the royal family only to find myself writing a second. The first book, The Prince of Mirrors, was about the ‘bad boy’ Prince Eddy, the Duke of Clarence. I’d written that novel because, despite the vast difference in our situations and the times in which we lived, I’d seen a lot of myself in Eddy and wanted to create an imagined version of his life. Right at the end of that book, Prince Eddy is about to marry a girl called Princess May of Teck but (spoiler alert) dies just weeks before the wedding. Almost before poor Eddy is cold in his grave, everyone from Queen Victoria down has the same idea: that May, and her strong child-bearing hips, should be ‘passed on’ to his younger brother Georgie, now the heir presumptive to the British throne. After a decent interval, May and Georgie were married, eventually becoming the stolid King George V and that ramrod-backed icon of monarchy Queen Mary.

I began to ponder the enormity of what had happened to this young girl in these early years of her long life. How had she felt about being expected to suppress her genuine grief over Eddy? And being used by what we now call the patriarchy as a ‘brood mare’ in order to secure the dynasty? Of course, the use of women as ‘brood mares’ for the monarchy was nothing new. Both Katherine Aragon and Anne Boleyn were such (though neither successfully). In the Stuart period, poor tired Queen Anne had eighteen pregnancies (though no child lived to grow up).

All of these women lived lives of unimaginable wealth and privilege and so would Princess May of Teck. But I began to think about what sacrifices she’d made, what it had cost her in terms of her own personality and potential as a human being. For it was crystal clear that the young May was a very different creature from the austere matriarch she would become.

May Teck was a shy girl, not a beauty. Unusually for royal circles, she was also artistic, cultured and well read. She was also good fun; happy to whizz down the stairs on a tea-tray. But May’s fate was to be married to a dull, philistine man who would dictate every aspect of her life until the day he died – right down to her hairstyle and the length of her skirts. These days we might call it coercive control. In late Victorian England, and in some societies even now, women were taught to regard their husbands as quasi-gods. Unluckily for May Teck, her husband was viewed as a literal god by a quarter of the world’s population. Not an easy ride.

To make the marriage work and to support the monarchy, which she’d been raised to venerate, this clever, sensitive girl realised that she would have to suppress her real self, develop a cold crust of inhibition and become the woman whom her son Edward VIII would once say had ‘ice in her veins’.

My novel Valhalla is about this sad transformation and the price May paid to lie forever as the revered Queen Mary in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, the resting place of the British monarchy. All the crowns, the jewels and the palaces were hopefully some compensation for what she lost of herself and whom she might have been instead.

I see May Teck’s story as a firmly feminist one which surely still has relevance to the #MeToo generation. In May’s time, the men in grey suits ruled the world and of course they still do. There’s a long way to go to reach equality and, in telling May’s story, I thought I might just help, in a tiny way, to underscore that injustice.

While working on Valhalla, one friend thought that, in the febrile age of identity politics and being ‘pale, male and stale’, I might get some stick for daring to write the story of a woman’s life.

As one human being, I just wanted to write about another. I told my tale of young May Teck because I felt sorry for her and wanted to imagine what she might have felt and suffered and yearned for. If anyone had said to me that I’d ever write a book about that stiff-backed, bejewelled old lady, the present Queen’s scary granny, I’d have thought they were mad. But when I discovered the young girl she once was, I knew it was worth doing. I wished that the times she’d lived in had been different because she might have been able to remain more true to herself; one of the most important goals any of us can achieve. I ended up loving her and I hope that readers of Valhalla may come to do so too.

Alan Robert Clark is the author of Fairlight Books’ historical novels The Prince of Mirrors and its sequel, Valhalla. You can find out more about Alan on his website, here.