Drunken Wasps on Rotten Fruit

Annie swore at him, and pressed hard on the doorbell.

‘You’re a difficult man to love,’ she said.

He took a step backwards and exhaled, glancing up at the star-pocked sky. The night was colder out here and he resented its damp weight upon him. He could not argue with her. He was a difficult man to love.

The house glowed like an inn, its interior blurry behind the stained glass. Annie tutted as her heels sank into the gravel on the drive and Adam resisted a bitter laugh. He’d only lose again. An outline jellied towards them from inside, black and brown, a dress and arms. Then the click of the latch, and he held his breath against the engulfing wash of extravagant food and the woman’s perfume.

A shrill laugh spilled over. It was going to be one of those nights. Another show.

‘Annie!’ the woman sang. ‘So glad you could make it!’

He watched as they bumped cheeks, standing in his rising breath as the doorway seeped heat. He was still angry, but obviously Annie wasn’t anymore. It was always like that. He unclenched his fist, painted nails leaving slithers in the soft palm. In his other hand he held the bottle, the 1982 red he had just said was too good for this lot. The temper that ruined him. Before, he might have smashed the bottle just to spite her, on a wall or a car. Or a person. He did that once. Then he’d be off, raging by the roadside. Now he was holding the bottle tenderly in the crook of his arm, label smiling up at him. He marvelled at how he had changed. How time had broken his spirit.

‘You must be…’ said the scented woman in the dress, toned and chiselled by fitness. Her voice rose in a question, although she did not need to ask.

They eyed each other for a second, the woman grinning, the same face they all made as their imagination met his reality. She knew who he was. She was about the right age. She would have read the articles, danced to him on the radio in her bedroom. Mocked and judged him later on. It was a long time ago, but people remembered.

Annie tugged him forwards by his fingers and presented him.

‘Steph,’ she said, stroking his arm, ‘this is Adam.’

Her touch was high in the sleeve of his T-shirt and she stared up at him, the black irises expanding in the night. The shadowed dark of a shark against the flecks of green. A tiny smile played over her lips.

He knew what this meant.

I love you.

Be nice.

Do a little more.

That was how it used to be, when he smashed bottles. Always a little more. Another interview. Just one more photo. Up the hill and down again. Then a final tour, a smaller venue and a shared bill. But it’ll pay.

Now there was nothing. Nothing but Annie and who he used to be. He was too sentimental. An open wound, that journalist had called him. He’d done well out of it, once. Not anymore. Now he needed her. She was proud and strong and harder than him, so he would do it. He could always do a little more.

He grinned at the woman in front of him. Steph, wasn’t it? Made the face he used to in the photographs, sucked in a little bit, though it didn’t make much difference these days.

‘Hi,’ he said. That was all. She was going red already.

‘Adam,’ said Steph, ‘I’m so glad you could make it. It’s wonderful to meet you. Really, really wonderful.’

She didn’t kiss him or shake his hand. He was a rotten fruit.

‘I’m so glad you could come,’ she said again.

Of course she was. They always were. She wouldn’t say anything yet, of course. That would be later, third bottle of wine, probably the 1982 red when it would be too late to appreciate it. Maybe a line on the table if they were daring, her hand on the back of his chair, or discreetly on his thigh. Then she’d tell him how great he used to be. How she loved him, once. Until she realised what he was.

‘We brought you a little something, Steph,’ said Annie. ‘One from Adam’s collection.’

She paused and so he held the bottle out.

‘Yeah, um,’ he said. ‘It’s a good one. From Lebanon. They grow it on bombed-out vineyards.’

He had no idea if that was true but a bit of fiction never hurt anyone. And nobody cared about truth anyway.

‘Oh, Adam, that’s wonderfully kind!’

‘It’s perfect for drinking now.’ There was no way she was keeping it for afterwards.

Steph studied the bottle, reading the label with unusual interest. Then she called out behind her, down the long, wide corridor.

‘Giles, darling! Annie and,’ she raised her voice now, ‘ADAM NORTH have brought a rather nice bottle!’

His stage name. Adam North. Better than his real name. No rock stars called Lamb, were there. Not back then. And there weren’t any called North now either. Not after what he did.

A man replied.

‘Bring it in then, girl!’ He had a deep, rich voice, sounded like the boss of the record label, the first one anyway. The one who owned an island. ‘And bring the singer too!’

More shrill laughter from inside.

‘Come with me, you two beautiful people. Let me introduce you to the others.’

Annie patted him on the bottom.

‘See?’ she whispered. ‘They like a drink here. Try and enjoy yourself for once.’

He took a deep breath and let them go ahead, pausing to check himself in a wide mirror with gilded edges. It looked expensive. It wouldn’t fit in his hallway. He was still happy with his reflection. He was beautiful once and the traces remained, a lost garden hidden under vine and dirt. The straggly hair and the infant eyes, the creases that were so strong in black and white. More beautiful than plenty of women.

He could hold a tune pretty well too. For a short while he was blessed by the stars, briefly attuned to the universe so that he could hear its melodies. He was irresistible, then. It was amazing, really. He would pick up his acoustic and the songs would just emerge, like flowers from his fingertips. And everyone listened. He was top ten in Canada, in Germany and the UK. And then, so quickly, it was over. One album and it was gone. Montreal, Munich and the Hammersmith Apollo didn’t care about him anymore, but the neighbours did. He was the new car on the suburban street, the final rocket at fireworks night.

The dessert at the dinner party.

He followed the booming voices, his boots ringing on the tiles and leather jacket rustling in accompaniment. His intro music. Sound followed him everywhere, even now, right into the dining room, if you could call it that. It was as big as his flat, exposed wood and a rising roof with a skylight and windows taller than him. Through the reflecting glass he glimpsed the garden, outlines of deep and distant shapes, branches moving like festival arms. They didn’t have a garden, these people, they had land. Annie was right about the wine.

The room was spotlit from alcoves and recesses, subtle and warm, shadows flicking against soft edges. In one corner fairy lights were hoisted and twinkling. He had to admit it was impressive.

But the room was quiet now. They were waiting for the introduction.

Steph was over by the kitchen counter with Annie, who was caressing the wooden countertop. It was laden with plates and bowls and fruit piled high like rows of seating. A magnum of something, glasses of different sizes lined up. The others were waiting by the table. An audience of three. A tense couple and a heavy-set man, thick with presence. They were waiting for him.

It reminded him of the silence on the stage, when he was coming up in the clubs, when he was solo and meant it. That early version of I Can Build You. They all listened then, when he could hit the high notes and still had tone.

Before his voice lost its soul.

Before he lost it.

Now the silence was something else. It was judgement.

Annie glanced at him, already distant. She always did this. Said it was for him to make an entrance, only he wasn’t so sure anymore. The large man barrelled over, sweaty blonde curls that thinned to a sore, red scalp. He was about Adam’s age but not in as good shape. He didn’t need to be. He stuck out his hand.

‘Adam North,’ he said. ‘I’m Giles. Steph’s keeper.’

‘Oh, Giles,’ said Steph in the background.

Adam shook his hand, felt the predictable strength. They always did this, the men.

‘Welcome to my humble abode.’

‘Our humble abode,’ said Steph.

‘Huge fan of yours, Adam. That song you wrote, what was it? The one from the advert, the bank one…?’

He turned around to the couple, tapped his thigh, hummed out of tune. There were flakes of skin on the back of his shirt. The tense couple grinned benevolently and the woman, small and plain and wrapped in glittering colours, laughed in shrill, broken notes.

Giles hummed a little more, switched to the minor change too quickly.

The woman was still laughing, with her beak nose thrown upwards towards the lights. She seemed nervous.

‘Come on, what was it called?’ Giles glanced back at Adam. ‘Don’t tell me! It’s coming. Such a great song.’

Giles turned back to the couple.

‘Help me, will you?’

‘Well don’t look at me,’ said the husband in library vowels, touching his thick glasses. He was sheltering in a heavy cardigan and a blue shirt, one hand in his pocket, the other holding the champagne. ‘I’m just a humble academic.’

He looked like one.

‘Professor, darling,’ corrected the woman, nudging him.

‘But not a professor of popular music, Jennifer.’ They both laughed at that, her off-key gasps echoing about them.

‘Do rocket scientists not listen to rock, then, Richard?’ said Giles.

The professor snorted. ‘Astrophysicists, Giles, not rockets. And no, not this one.’

‘So we can’t help with the song.’ Jennifer was smirking. ‘So sorry. Though I’m sure we’ll have heard it on the television.’

‘Not that we have much time for that,’ the professor said.

‘I’m sure you’ll know it,’ said Giles. ‘It’s a classic. I just can’t remember what it was bloody called.’

‘Oh Giles,’ said Steph, ‘stop teasing Adam North.’ His full name again. She smiled at him briefly, then started flicking at a phone. ‘It was this one. I Can Build You.’

‘I Can Build You! That’s it!’ Giles had his finger to his nose, as though he had just won charades. ‘Stick it on, girl!’

Oh Christ. Adam found a wall to lean against so that he wouldn’t have to dance to himself. He braced for his past. The strummed chords emerged from hidden alcoves in the ceiling, then the drums and that terrible gated reverb that was so on trend back then. I Can Build You settled into the famous, loping rhythm, and then the drums fell away to the first verse, his distinctive voice cutting over the guitars. Too distinctive, really. When it all went wrong, later, there was no denying it was him, even without the pictures. The sound of it on the tape was enough.

He watched the others. Steph and Annie were moving a little, which was kind of them. Giles was patting his thigh again, champagne dripping onto the tiles that were definitely marble.

The professor in his cardigan and his little beaky wife were completely still. Listening. Really concentrating. But I Can Build You didn’t merit too much thought. It was a good song but it hadn’t aged well, Adam knew. Otherwise he’d be the one living in this house.

The song came to the end of the second chorus and Steph swiped and the warm, rich sound of a band who still had a record deal came on.

‘Do you know these, Adam?’ she asked.

He shook his head, though he did.

‘No? Really? You don’t know Darkening Skies?’

They had supported him at the Arena gig, a decade ago. The peak of it all. They were kids then and he was top of the charts and so of course he ignored them. He wouldn’t mind their help now.

‘Darkening Skies? Oh yeah. Sure. Good mates of mine.’ He pointed at his right ear. ‘Sorry, I suffer a bit these days, you know.’

Giles made a sympathetic face.

‘The price of success, eh?’ He held the edges of his stomach in one hand. ‘We all have a price to pay. Even the professor here.’

The man in the cardigan shook his head.

‘Oh, I don’t know, Giles. There isn’t any price to pay in academia.’ He touched his glasses again. ‘Too much reading, perhaps.’

‘But you are successful,’ said Jennifer, suddenly grave.

He peered at his wife as though examining her for a condition.

‘Not in the same way, darling.’

‘Come on, Richard,’ said Giles, ‘you bloody well are. What about all those prizes? All those books you’ve written?’

The professor removed his glasses, and cleaned them with a cloth that he lifted from a pocket in a practised gesture. He was used to performing too, Adam thought.

‘Well, that’s certainly true. I’ve been referenced almost 500 times in the past two years. Which is quite something, if you’re in astrophysics. I’m quite famous, in my universe.’ He looked up. ‘If you’ll pardon the pun.’

Jennifer smiled brightly at them all and they nodded in reply. The professor was staring directly at Adam.

‘But I’m certainly not like you, Mr North,’ he said.

Adam straightened up against the wall and glanced across at Annie. Her arms were folded but she was no closer to him. He coughed and cleared his throat.

‘No?’ he said.

‘No,’ said the professor. ‘I’m not famous in the same way, you see.’

There was silence again. The judgemental sort. Adam waited it out. He knew it would pass. It was Steph who broke it, coming round with more champagne, her shoes rhythmic on the tiles.

‘So Richard has damaged his eyesight, and Giles is a glutton.’ She smiled and they all did too. She came close to Adam and held his eyes as she filled his glass. ‘And Adam North has lost a little hearing…’

He liked her smell. She was musky and rich. Or perhaps that was the house. She turned to address the others and Adam admired her rise and curve.

Outside the night had descended so completely that the windows were entirely black, as though they were entombed by their own light.

Giles made a toast.

‘To the damaged!’ he cried.

‘To the mended!’ Annie added, raising her glass to Adam.

Adam tilted his head back, eyes fixed on the skylight and the stars that burned invisibly outside. Then they made their way to the heavy table, where the couples were separated, their alliances broken. Annie was close to Giles and the professor at one end, with Adam and the wives at the other, beneath the flashing fairy lights. They were on competing stages, their conversation loud beneath the swirl of music above them.

Each dish was more striking than the last and Adam relaxed as they settled into the meal, slices of chilli-dressed fish and fresh salad leaves from the garden, which Steph claimed she grew herself. The wine was very good and when Giles opened Adam’s bottle he insisted on serving him first, leaving the bottle at his end with a knowing look.

Adam settled amidst the drink and the gentle passing of the plates. Giles and Annie were absorbed in the professor, wearing serious expressions and taking short, considered sips, and he did his best to entertain Steph and Jennifer, working through his well-rehearsed anecdotes, the tours and the TV shows and the mishaps with minor, faded celebrities.

By the time dessert was served, along with an ancient and impressive Tokay, he had started to appreciate Jennifer’s piercing laugh. She was definitely nervous, he decided. She could barely look at him. She reached for Steph at every punchline, as though she needed her confirmation that this was really happening. He understood. She simply could not cope with the strangeness of eating with Adam North. She was a fan, from before, like Steph. It was why he was invited. He was the dessert at the dinner party, wasn’t he? He didn’t mind anymore, now he’d had a few drinks. His edges were smoothed. Now, he welcomed their laughter like applause. Steph kept his glass full and her knee was against his under the table and he had to admit he was enjoying himself. Who knew what might happen later.

But he’d had too many already. When she poured the Tokay he made another joke and they both fell about and then he finished the wine too quickly, like he used to. And now he was teetering. The alcohol held him and spun him, and he could remember that familiar darkness where his shine was dulled and his guts revealed, like the mud beneath the retreating tide. He realised Annie was watching him, with that eyebrow of concern. He stood and it was too fast and the table moved, though he did not think the others noticed.

‘Excuse me, will you?’ he said to Steph and she touched him on the wrist as he bumped the edge of the table again. There was potential, here.

He weaved across the empty, booming space, heading for the dimmed corridor where the bathroom might be. On the walls were clustered photos of men and women in black and white and he paused to steady himself, leaning against the cool plaster. May Ball, he read. 1999. He ran a finger across the glass and found Steph quickly, the hair and sharp bones the same. He left her smudged and smeared.

There were two doors on the corridor and the furthest one was open with the light on. Muttering to himself, he pushed against the first door anyway, holding his breath as it creaked and opened onto warm softness. Some sort of huge drying room. Clothes hung about him on wooden racks. Towels and sheets and, at eye level, socks and underwear and a solitary black bra. Slowly he fingered the lace, his heartbeat loud in his ears, Steph’s finger light on his wrist. He saw Steph taking it off, smiling up at him, poised on the edge of the bed. This house should be his, he thought. He should have her. He closed the door.

In the dark toilet he stumbled a little as he tried to grab the switch. It swung from him in the arc of a metronome. He gave up and left the door wide, using the light from the corridor as he lifted the lid with a clatter. He was a little aroused, he realised, from the bra. Highly sexed, Annie called him, like a panting dog. Resting one hand on the wall, he urinated directly into the water, enjoying the loudness of the froth and rumble. It took some time to finish and he made a small pool on the tiles between his feet. He took some paper and wiped his boots, ignoring the rest. Giles looked like a floor wetter anyway.

Wiping his hands on his jeans, he closed the toilet door behind him and started back towards the table. Jennifer saw him and rose from her chair. She loved him. He had entertained her. She was his fan. She wanted a moment with him, no doubt. Then he realised she might need the toilet too, and regretted not cleaning up. He decided to wait for her by the photos. He would pretend to be a bouncer. That would make her laugh and then she wouldn’t blame him for the mess he always left.

She came closer and he made himself broad and square. He narrowed his eyes and grinned.

‘Security,’ he said and held out his arm to block her path.

But Jennifer did not smile. Quite the opposite, in fact, when he thought back to it. As his arm came up it looked so large compared to her, so heavy and strong and threatening, and he knew he was wrong. As his arm came up, she seemed to clutch at herself, to shrink and recoil from him. And then, finally, she looked at him. For the first time, he realised. She really held his eyes. And she was alive and angry. It was an expression he remembered. From before. From back then. He felt his balls rise into him.

It was like when the lights were shone onto the crowd, all those years ago.

But she did not love him.

‘You disgust me,’ she whispered.

‘What?’

‘You disgust me,’ she repeated.

He gave a small, nervous laugh and she pushed past him, pressing his arm down with a force he remembered. He listened as she hurried to the bathroom, closing the door hard. The lock slid loudly into place.

You disgust me.

He could not move.

You disgust me.

He’d been so sure she was struck by his light.

He was sweating and damp against the wall. Across the room Steph was quiet at the table, her back straight, her neck long and delicate. He remembered his nails, seedy against the lace. He hated himself. He hated who he was.

He staggered back to the others, and there was no music playing. Just the fireside murmur of conversation from one end. The professor held his glasses in one hand as the fairy lights flickered about them, tiny satellites in the sky.

Adam sat down and Steph smiled, her lips stained in wine. Did he disgust her too? She filled his glass again. He wanted to speak, to ask her. Had she always hated him? But the words, like the songs, wouldn’t come.

She shuffled closer and he smelled her perfumed heat as she held the back of his chair. Perhaps Steph still loved him. She had blushed when they met. She knew his song. Steph understood. She knew success and money. She knew how it twisted a man.

She leant in and he felt himself returning. He needed this so much.

‘So… Adam North.’ She smiled.

It was going to be OK.

‘It must have been hard for you,’ she said. ‘The way it all ended.’

He looked at her and then away, his cheeks flushing.

‘You must have found it very traumatic.’ She reached for his hand. ‘It was so public, wasn’t it? So humiliating for you.’

He was without words.

‘It might help to talk about it,’ she said. ‘To talk about the bad, as well as the good.’

He tried a smile. His voice was a whisper.

‘Have I been going on?’

She squeezed his fingers. ‘No, not at all, your stories are all… well… from another time. It’s like another world.’

He wanted to ask her if she found him disgusting too. Only he was afraid of her answer.

She leant in closer.

‘You can tell me. What really happened in that room. You don’t need to be ashamed.’

He stared at her hand on his and then at the empty bottles of wine on the table.

‘I know, sweetheart,’ Steph murmured, her breath in his ear. ‘You can tell me.’

Then her forehead was against his. Her skin was soft and warm and he was disgusting, it was true. And the music was swirling too loudly about him and his mouth was dry from the wine and now the talking had stopped, and there was a ringing like tinnitus that he needed to stop.

Ping ping ping ping ping, it went.

Giles was tapping his wine glass with a spoon. It was quite percussive.

‘I’d like to make a toast,’ he said.

Steph sat up and pulled away, and he missed her heat on him.

‘To our famous singer, the first ever to grace this house! To Adam North, to his music and his talent!’

They raised their glasses. It wasn’t even his real name.

And then a shrill voice echoed across the wide, marbled dining room.

‘What about you, Richard? What about your talent?’

It was Jennifer, shrouded in the corridor.

‘What about the price you have paid?’

She stepped out onto the cold, hard floor, where she was caught and released by the flickering lights. She was quivering in anger.

‘What about the prize, Richard?’ she cried. ‘What about the Steer’s Prize?’

Nobody spoke as she paced straight over to Steph, touching a brief hand to her bare shoulder.

‘May I?’ Jennifer asked, and took Steph’s phone from the table.

She skirted around the table until she reached her husband at the far end, where she sat down without grace. Her voice was calmer now.

‘Tell them about the Steer’s Prize, Richard,’ she said, not looking up from the phone, her fingers moving.

The professor gnawed on his glasses, pondering the request.

Then the music started up again, only now it was very quiet. Jennifer had chosen it. I Can Build You. His song. She glanced up at Adam, and he thought he saw a swear word on her lips.

The professor began, speaking in measured words for his special audience.

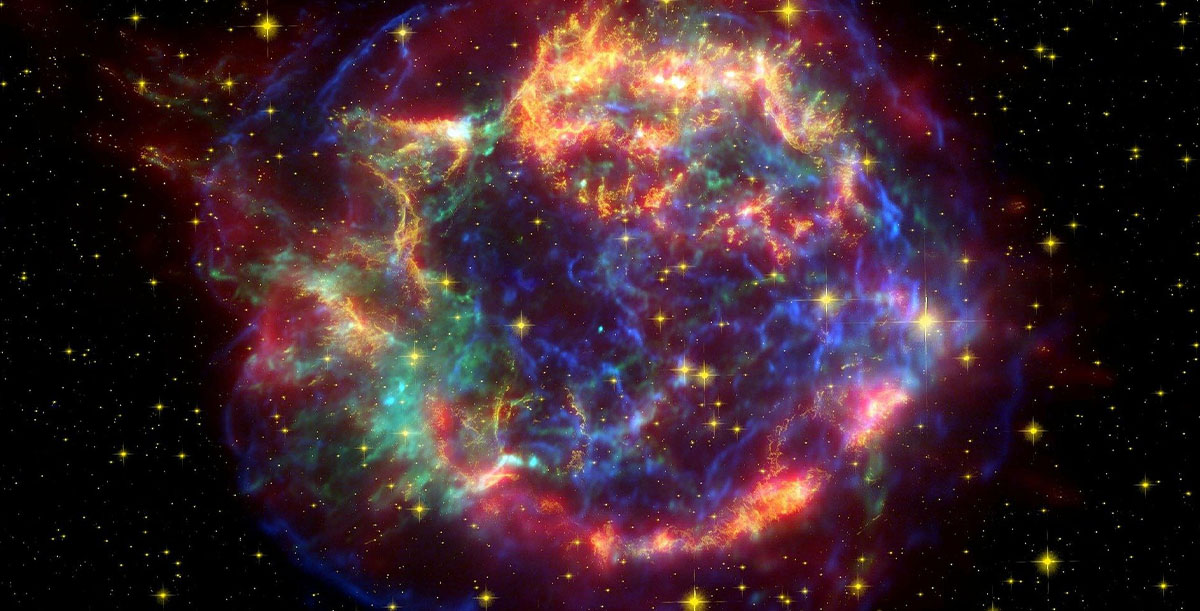

‘I won the Steer’s Prize last month,’ he said. ‘It is the defining moment of my career so far. It means that my work has been recognised. That it has value.’ He gazed up at the skylight. ‘That I will be remembered.’

‘And remembered well,’ said Jennifer, in a clear voice.

Steph reached for Adam’s hand again.

‘I won it for my contribution to the study of the lifespan of stars, and to black holes specifically.’

‘I’ve always been frightened of them,’ Annie said, in a voice Adam did not recognise. ‘Of black holes.’

‘Frightened?’ said Richard. ‘You mustn’t be frightened of them, Annie.’ He sounded almost tender. ‘They are simply stars dying, after all. They are quite fascinating. Do you know how it happens?’

Annie shook her head like a child. The professor gestured towards the skylight, at the looming depths of the night.

‘I will keep this simple,’ he said, and Adam wished he would finish. ‘As stars expand, they use up and deplete the hydrogen around the core that is their fuel, and become what we term “red giants”. Are you with me?’

There was nodding.

‘Our wonderful sun is a red giant, as are other stars of a similar mass. When stars of really significant mass use up all of the hydrogen, it follows that they are termed red super-giants.’

‘Tell them what you told me, Richard,’ said Jennifer, ‘about how stars die.’ And she glanced at Adam again and this time he was sure.

‘Well, the red giants simply fade away. Most of them. But the dying of the largest stars, those with greatest mass, the red super-giants, is quite incredible. They explode into what is termed a supernova. The layers of this supernova fall away, or rather are thrown out into space, so that only the core remains.’

I Can Build You was still playing from the ceiling, but nobody was listening.

The professor traced a circle above the table with his glasses, his arm extended.

‘The core begins to shrink. It reduces in size, as though the star has simply become too large for its own essence.’

‘And then?’ prompted Jennifer.

‘And then, well, it depends on its mass. It may produce other stars, known as neutron stars.’

‘Or?’

‘Well, this is where we enter my particular field. If the core is of sufficient mass, that is to say if it is truly massive in the first place, it is simply too large to create other, smaller stars.’

He smiled at Annie, a small smile that seemed to know more, and she looked away. He pointed his glasses back at the skylight.

‘The core then collapses upon itself,’ he said. ‘Into what we term a black hole.’

The professor looked around at them all.

‘No stars are produced. No light at all, in fact. The star collapses into absolutely nothing.’

Adam realised that Jennifer was staring directly at him, an expression of triumph on her face.

Nobody spoke. His song had started up again, on repeat. Adam bent his head. On the table, between his hands, the wine glass caught and reflected the flickering of the lights. Off and on. Off and on. It followed a pattern and pulsated with charge.

‘Black holes aren’t really black, of course.’ The professor seemed pensive. ‘Not everything in the universe is as it seems.’

Jennifer made a strange sound that was loud and high and perhaps strangled.

‘Black holes are rather misnamed, in fact. It is simply that no light is able to escape.’

The professor turned to Annie again.

‘So you see, a black hole is nothing to be afraid of. It’s simply a dead star that has collapsed on itself.’ His glasses seemed to be pointing in Adam’s direction. ‘A star that emits no light at all. It isn’t anything at all.’ He paused. ‘It is, in fact, nothing.’

The silence sang in Adam’s ears. It stretched and hummed and it was louder than his music. They were judging him.

Ping ping ping ping ping.

Giles was on his feet, sweaty and drunk.

Adam looked up.

‘To black holes,’ said Giles.

Jennifer raised her glass. She smiled at them all.

‘To dead stars,’ she said.

If you enjoyed this story, read E. J. Saleby’s loosely connected short story Atoms.

For more short stories, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.