Dobson’s Ministry of Deliverance

Just as April was bidding its farewells, apologising for being a bit miserable, damp and sodden, a brazen sun arrived. Like all wandering friends it was champion to have the sun come home; the old chap was full of conviviality and warmth, hinting at tales of the deserts and tours over the tropics and the like. By June it had outstayed its welcome. Thermometers had never been so antic. Mercury rocketed to heights long obscured by baccy stains: bewilderingly high numbers for County Durham where three fine days harbingered rainstorms, signifying the end of summer.

Not in 1976.

Such heat was first a novelty and then a bloody nuisance, turning all manner of decent village folk scatty and it wasn’t unusual over those hot months to see a ragbag crowd of men and women gather beneath the shadow of the pit wheel, fancying it turned like a fan and gave off a bit of relief. It did nothing of the sort. There wasn’t a sniff of a breeze hanging about to riffle through those colliery terraces, ‘The Rows’ as pit folk called them. The Rows ran and ran, neat as plough furrows over Coal Board acres, terrace after terrace below the pithead. Blucher Road starts the run and Bleaney Street ends it, mind you the terraces in between fancied themselves posh, named after royalty, generals and the odd Prime Minster – most of them forgotten being long dead and mostly Victorian.

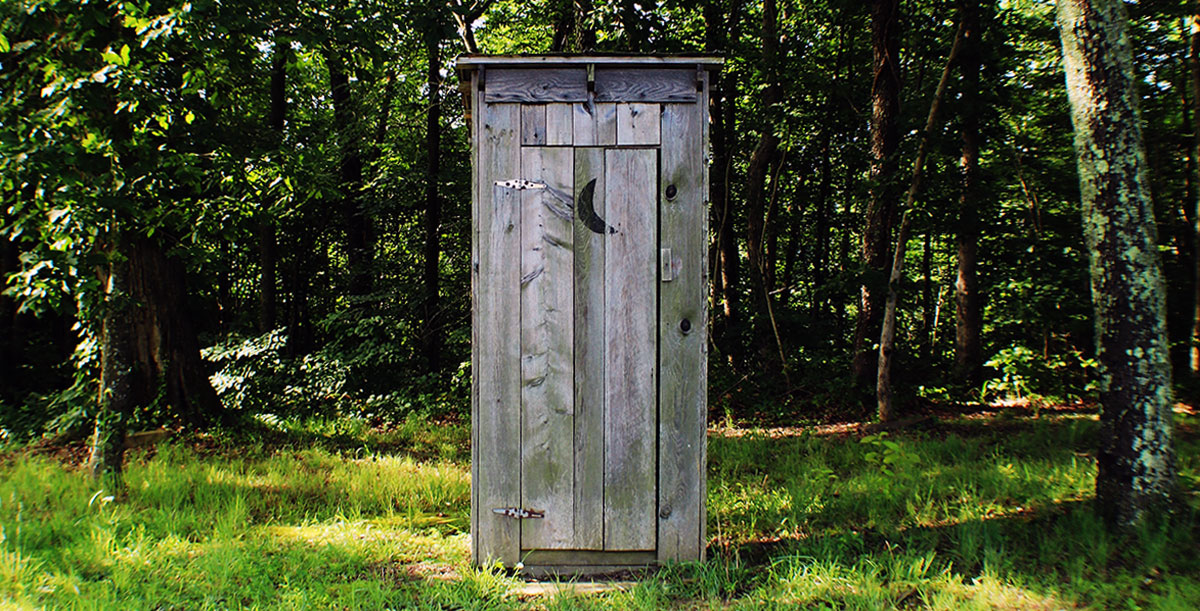

Alice Dobson lived in Bleaney Street. Her neighbours had taken to calling her the Widow Dobson – which she was – to differentiate from Alice Dobson of Gladstone Street who still had a husband living although he was often dead drunk; so she was a widow to the bottle so to speak. Anyhow, the Widow Dobson of Bleaney Street was having a bad summer or a fouler one than most. She’d gotten herself a lodger, one she hadn’t advertised for in the window of Jackson’s paper shop or anywhere else for that matter. As far back as she could date it the lodger appeared just after a big electrical storm, moved in all of a sudden, taking up residence in the garden or more precisely: her garden privy. It was an annoying thing to have about, a curiosity, a curse, a puzzlement and a pest that possessed an almighty allure for cats.

Same time every evening, waking from sleep on roofs and nooks, sheds and larders, the cats of the colliery village gathered in the garden of the Brown Jug. All manner of cats mingled in this hadj, ear-shredded moggies, feral farm stock, velvet-collared lap curlers with tinkling bells and pet names that would shame their Egyptian forbearers. Then, grouped like runners in the Grand National and summonsed by something only they could hear, off they would set; scurrying out and down the cuts between the Rows, chased by collier kids who raced the zigzagging pack until all came to a leaping halt onto the walls of Alice Dobson’s backyard.

‘There’s not much to it,’ says Helen Outerside, holding up a skimpy blue Baby Doll nightie. She’d bought it years ago when the fad was at its height, worn it once, felt frilled up like Coco the Clown and packed it away again. Now she needs it. Far lighter than her usual winceyette, a Baby Doll can be washed and dried in a twinkling; that’s the blessing of Nylon when she comes to think of it, an hour on the washing line, snap your fingers and it’s fit to wear. Given her predicament, this is the kind of laundry turnaround she needs. ‘The neighbours must think I am incontinent,’ she says to herself, and sighing reflects: ‘well, the neighbours can just go an’ bugger off.’ Helen folds the Baby Doll and places it on a nightstand ready for bedtime. Bedtime? Man, does that word sound cosy, but for Helen the very thought of it makes her shudder.

Helen has had the most vivid dream for weeks, the same, night after night, going on for a month. Lying in bed she feels these two great hands take hold of her shoulders and shake her like a doll. She wakes up, or dreams she does, and there’s Bob Dobson’s face, caked white, tears streaking down his cheeks. Next the white stuff starts cracking off his face, flakes of it falling like petals of plaster from a bad ceiling, down it comes in showers dropping into her mouth, filling it up! Salt, bloody salt, clogging her throat, burning her tongue, stinging her eyes. Choking, panicked and bloody petrified, she tries to heave free of his grip. But Bob’s got tight hold of her and his shaking becomes all the more frantic, his black mouth writhing, forming soundless words. She’s certain he’s mouthing Helen, Helen. ‘Bob! What, Bob?’ she yells back at him and shouts herself awake.

Heart still sprinting and wide awake, she smacks the sides of the bed with fisted hands, shaken and vexed by Bob’s thieving of her sleep. Clammy as a wet flannel her cooling nightie sinks into the folds of her body. Staring wide eyed at the dark ceiling she tries to ignore the sticky, cloying feeling of soaked cloth against her flesh. It’s just too nasty. Moving gently onto the side of the bed, wincing at the sound of the mattresses springs, she pauses to listen into the night, checking if she’s woken her daughter Susan. She hasn’t and never has for as long as this dream’s been besetting her. But then Susan slept through the last pit disaster, dead to the world when the whole village was on its feet. Helen blames energetic discotheque dancing for Susan’s ability to sleep like the dead, all that jumping and hopping and God knows whatting.

Peeling off the damp nightie she stands naked in the middle of the bedroom, padding herself dry with a hand towel and feeling tearful. Finding a fresh nightie on the nightstand she changes into it, the dry cloth giving her some comfort. And then, true to routine, she traipses downstairs to sit in the back bar. Curtains drawn, she doesn’t switch the big light on lest it attracts some dirty stop-out fancying a lock-in is going on in the Brown Jug. Pouring a brandy, Helen smokes a couple of tabs and wonders whether she’s dying. Bob, the sweats, mind and body in cahoots sending out signals that she’s sick, sickening.

‘I am bloody sick, sick of all this three-in-the-morning malarkey,’ she says out loud. Taking another sip of brandy, she reproaches herself: ‘Am fit as a fiddle,’ and then: ‘It’s the change is all it is. Mam had it early; she was about forty-five when it started.’

Minded to give sleep a second chance, she’s placing the ashtray on the bar when another thought flits her mind: ‘Or Alice Dobson’s cursed us. It’d explain Bob like. And after the goings-on at his funeral.’ She wonders if this suspicion deserves another brandy.

‘Howway!’ she says to herself, ‘if I start believing in the power of curses a’ might as well embrace the Virgin Mary.’

Helen has no truck saints, saviours, holy scents and candles and this marks her out as unusual around these parts. A couple of thousand years of Christianity, decades of scientific discovery or even common sense hasn’t curbed this little community’s readiness to conjure up the supernatural for the causes of stuff they’re too idle to reason out. But why Bob should be turning up in her dreams and in such a shocking fashion she just can’t fathom. It’s been years, years! since he died. Her own husband journeyed the track to the crem’ back when Susan was hardly walking: why hadn’t he bothered to turn up in her dreams? He was punctual in life. Come to think of it, he was an easy going so-and-so, never jealous or nasty so it makes sense he wouldn’t show up in nightmares, haunting her for having other fellas after his death, fellas like Bob.

Bob? Aye, she loved Bob Dobson or, more properly, was in love with him at the time he died. The affair was still on the up when he had his heart attack, and Helen is worldly enough to know peaks are crested and they’d have gone their own ways before tongues wagged, or wagged the more. She’d never have married him. She could never have married him; Bob wouldn’t dare leave Alice. A big strong fella like that afraid of that little bird of a thing. Helen thought he was having her on; he used powerful once to describe Alice. Helen teased him, tried crack his deadpan expression:

‘Powerful? Powerful? All ye fear the mighty Alice… Eh?’ Helen bantered on all supercilious, while Bob’s face remained flint. There was no joke about it: Bob was a-feared of Alice and her old Romany blood.

Returning to bed, she does fall asleep but it’s not the good stuff. The regularity of this routine is running her ragged. Last Sunday the Brewery stocktakers turned up at eight in the morning, and she must’ve looked a proper fright, standing over the bar and holding ice cubes against the bags under her eyes. Never one for big lie-ins, she can’t work the day without a good sleep – so much so, Susan’s had to check the dray deliveries three weeks on the trot. Draymen can be fast lads, but Susan’s wise to their cadging monkey tricks.

Nelly Latimer stands on the vicarage doorstep, bothering Reverend Angus like a wasp around a beer glass. Anglican holy men are a mystery to her, but it’s not his faith that’s making her so nervous. Barely on nodding terms with the man, Nelly has heard an awful lot about this vicar. Angus hales from affluent Gosforth and his reputation amongst his labouring parishioners is something shabby. Like cheap French scent, a sanctimonious attitude wafts off him and his wife, suggesting their being here is a personal sacrifice for which The Rows ought to be eternally grateful, Amen.

Nerves and Gosforth persuade Nelly to use her best voice. It’s a parody of posh, picked up from the picture house and avid watching of Upstairs Downstairs.

‘She knows you’re High Chorch, you see, believe in owt and likely have fantastical ideas, which’ll mek you sympathetic to her aggravated plight: the ghost a’ mean. And a’m sent out to fetch you, see?’

Gob aslant like a cow mid-cud its patent Angus cannot understand a word.

Nelly pats her neck with a floral print hanky. It was too hot to wear a headscarf but she wore one anyway, pulled it on along with her heavy coat, rushing out to do Alice Dobson’s bidding. Nelly Latimer’s always been a dasher and fetcher for Alice. Out in all weathers and it’s never a problem. Why Nelly does it is a vexing riddle to all those geeking at her gadding after this and that. It was the same in the schoolyard, one tug from Alice and Nelly came running as if bewitched.

Nelly tries again. ‘Man! she cannit get close to her own netty: it’s animated! She’s doing what has to be done at 25 or 27. She takes her own toilet paper like, a’mean strips of the Evening Chronicle as she’s not fash on buying paper special for the purpose. So you see 25 and 27 is dead fed up with her as she’s always in and down, up and out. A mean she can’t use 27’s backyard gate because old Dawson’s shored it up to fashion a chicken coop, so she’s through the house all the bliddy time! Hey and what’s more? I tell you what’s more: the bliddy noise! Whey! Vicar! Puts the bairns right off their tea. Whey, once it starts, man it’s deafening!’

Angus responds by closing his mouth and opening it again.

Nelly’s heavy coat pricks her into a proper bad fettle. She’s had rashes all summer and Alice’s ointments do nowt to easy the itch. ‘Shall a spell it out again?’

‘Please,’ said Angus.

Please, thinks Nelly, this is his first word he’s tried and out it comes like a bairn just born bawling at a midwife’s slap, and the whole while keeping me on the step like some dirty bliddy hawker.

Nelly’s about to repeat her tale when she sees Lydia, the vicar’s wife, flinging about a dishcloth trying to signal his tea’s on the table and going clay cold.

‘Your wife’s radging about like an airman,’ said Nelly, thinking, Oh, he fancies I’ve been impertinent, and his bit mouth’s turned all poky in that awful nesty beard. She wants to laugh at his sudden petulance but thinks better of it, Alice needing his help and all.

Angus looks over his shoulder. Lydia blazes the eyes of a gorgon.

‘Bring the widow Dobson to me,’ says Angus, ‘and mind, Mrs Latimer, do not return until a good hour has passed.’

Reverend Angus watches Nelly Latimer skit down the vicarage path, her heavy coat adding the impression of some startled woodland creature. Feeling the hot furnace of Lydia burning behind him, he wants to keep watching the retreating gofer and not turn round.

‘Angus. You do get a day off. This is your day off. Send the mentalists to Rowlands Gill,’ said Lydia, slapping the dishcloth over her shoulder.

‘Lydia, I do not get a day off. This is my parish.’ Words out and Angus watches his monumental pomposity take a bow and wave to the world.

‘Oh Piety,’ snaps Lydia. ‘Go eat your quiche.’

The slim woman makes herself all the more angular resting fists on hips and sticking out her elbows.

‘It must be serious, darling.’ Angus smiles at his wife in a way he considers loving and she interprets as condescending. ‘Tonight is bingo night at the Bank Top. They never miss bingo night.’

‘By royal command, bingo night at the Club and Institute Union! Fetch my pearls.’

‘Lydia! The CIU, as you know …’

‘Evidently, I know as much as you. Bingo night indeed and you suppose they plan to miss it? How? It’s not gone five-thirty, the club doesn’t open until seven… or so I believe.’

Lydia was going grey in this parish. It was supposed to be a five-year posting, do your bit in the slums and then move on, land a chocolate box rectory sermonising to the county set. A decade, they had been here – and a long pitiful decade at that!

‘Well, Mrs Latimer hasn’t done her hair, darling. Rightly at this time of day it should still be in or just out of curlers.’ Angus hung that smile again.

‘Did you just say “done her hair”? You’re going native. You’ll be calling a toilet “the netty” next, like that yappy woman who’s just infested us. I’m going to call Uncle Tony, Angus. Enough is simply enough.’ Lydia’s Uncle Tony is the Archdeacon of Lindisfarne, and although a great luminary in a different diocese he remains an ecclesiastical heavyweight north of the Wash. ‘And I shall beg him on my knees for a parish in Corbridge. I might even aspire to Hexham!’

‘Darling, it simply doesn’t work like that…’

‘Golly goodness, it doesn’t! Look at Charlie Atikin! Two years on hospital radio and they made the boring old toad a canon with a fine living in Middleton Tweedsdale! I want stepped lawns Angus, rose gardens, cake competitions. I want somewhere verdant, Angus! I want to judge jam in a place where there’s not a pit heap in sight …I want, God forbid, civilisation. I’m fed up with leek shows and pea and pie suppers, harvest festivals here remind me of some Russian author’s squalid idea of the bucolic …’

Angus retreats behind a tower of salad cream, a wall of lettuce and a redoubt of quiche. Actually, it’s a cheese and onion flan. Lydia’s set a trap. If he contradicts her and calls a quiche a flan: snap! She’ll be straight onto the sherry bottle and Friday night will be all torment and tears.

Eating a forkful of flan he remarks, ‘Oh this is splendid darling, thank you!’

Deflated, Lydia throws the dishcloth at the sink gives a bitter Huh and says, ‘I’m going to watch the news.’

Alice Dobson? Of course Angus remembers Dobson. Of church attendance she was never devout, a fair weather faithful, a Christmas caller, an Easter peeper and that about summed up the scale of her devotion. In a swarthy sense she had the look of Rome about her, dress-wise she was more buttoned up than the most fervent Presbyterian. Then her husband died and these slender church calls stopped completely. Angus buried him. They’d no children, or rather there was no mention of children in the ‘didn’t-he-do-well-in-life’ eulogy, nor was there any sniff of a wider family at the committal. The funeral was… Angus wracked his memory… quite some years ago. Bob Dobson was found dead in the outside toilet: the netty. Maybe he should start saying ‘netty’, that’d vex old Lydia.

A man called Dawson broke down the toilet door. Ivy, Dawson’s half-sister, arranges flowers in the church. Lydia thinks Ivy a bit ham-fisted at flower arranging; Angus has no complaints. Poor Bob Dobson dead in the netty, arms crossing stomach, typical of a heart attack. He was fifty-four years old.

Coal dust got him, thinks Angus, chasing a silver-skin pickled onion with a blunt tined fork, coal dust: that jet-black adjunct of death for pitman: if work, the props, the shaft doesn’t kill them, the assassin lies in their lungs. Hard drinking and cobble boxing do for some, but dust, dust is the general undoing of them. Coal dust. And God knows I am a traitor to these people, praying as I do for the death of this savage industry. And my prayers, it appears, are slowly being answered and Lydia’s too no doubt.

What Angus gleaned from Alice Dobson when they met to plan the funeral was the startling degree of love she had for her husband. Dear God, what a limping half hour that was, punctuated by weak tea and malted milk biscuits, the middle minutes spent grinding out a pinch of biography from the living about the dead. For Alice, Bob Dobson was the model husband. Drank at the Bank Top and the Jug Inn, never late for lunch or dinner. Box of Black Magic chocolates every Sunday; she confessed she was never fond of that make of confectionary, but she’d never told Bob. Flowers and rings, a birthday never forgotten, anniversaries always celebrated. It all seemed too, too rosy and when matters unravelled in public the way they did, well Angus wasn’t in the least surprised.

Burial is unusual for Anglicans around these parts. Alice had said she wanted Bob near her, not atomized into dust, into ash, but ‘whole and on this plane, so to speak, vicar’. A committal to earth or flame, a nuanced textural difference, either way it doesn’t much matter to Angus. Of course banging on about ashes to ashes at the Crematorium that’d be crass and somewhat too close to home. Whether grave or furnace the outcome is the same in the end, the hot choice simply speeds up the inevitable: embalm away and mummify, nothing lasts forever. Angus stares at the cheese flan, and thinks some things after all could buck this rule.

Angus lays down his knife and fork and calls out, ‘Thank you, Lydia!’

Alice had said she wanted Bob near her, wanted to lie by him when her time came. ‘How that changed!’ Angus said to the plate he was washing.

Alice Dobson loved dead Bob right up to the very edge of the grave, right up to the moment Helen Outerside, then and now landlady of The Brown Jug, had what they call ‘a turn’ or rather a ‘reet turn’ at the graveside.

Women at funerals? Not approved of. Old pitmen don’t like it for the very reason Helen Outerside exemplified: bawling out – crying – hysterical… A gut blast deafening as a quarryman’s charge! Louder than anything Angus had heard outside of the opera house. So much so, if one was uncertain of which mourner was the Widow Dobson one could be forgiven for thinking it was Mrs Outerside.

Poor Alice. The whole village saw – if they had not already seen – what was up and what had been. Helen Outerside and Bob Dobson. Dear God! Everyone in that precise moment knew what the widow Dobson now understood: her high-pedestalled man was an adulterer.

Angus is certain it was Nelly Latimer who helped a stunned Alice out of the graveyard. He has a faint memory of watching them leave as he picked up the committal service roughly where it’d been screamed off and all the while Helen Outerside wept like a tap.

The morning following the committal Angus walked through the graveyard on his way to the church. Bob Dobson’s grave had been wrecked. Wreaths scattered, flowers shredded, the grave white with salt and empty Saxa cartons cantering around the graveyard possessed by a breeze. Shocking. And the coup de grace of desecration: an upturned bottle of stout stabbed into the earthen mound of the grave. As to the identity of the vandal? The incident wasn’t reported. A month or so later Angus was informed by the sexton there would be no headstone. When chasing up the monumental mason on another matter, the sexton was told Alice had cancelled the order on the very afternoon of the funeral.

And so poisoned earth settled over Bob Dobson, a barren rectangle readily identifying his resting place amongst the headstones and the flowers decorating the domiciles of his fellow dead. Then in late June a sudden storm seemed to single out the graveyard. Clouds gathered over those few acres and tipped their gallons as if their guts had been ripped open by the beak of the cockerel atop of the church spire. Rain pounded on Bob Dobson’s rectangle, cleansing the soil and summoning up life, and within weeks dandelions and daisies thronged over his memory. The untended grave, being in the newer part of graveyard, was something of an eyesore compared to its spruce and flower-covered neighbours. Angus should mention this to Mrs Dobson when she arrives, should mention it but he has every expectation that he won’t.

Nelly swelters back to Alice, her fawn three-quarter camel hair coat now firmly rolled under her arm. Back and forth like a bobbin — Nelly do this, Nelly gan there — and she’s proper lathered and exhausted. By the time she reaches Alice’s door she’s tied her headscarf around her throat like a collier to stem the sweat.

‘He said what?’ said Alice. ‘Me to him while the problem’s back here? The proofs in the backyard. The fella’s an idiot! Gan back Nelly an’ tell him come here. Nelly?’

She cannit abide the clergy especially after Bob’s funeral, thinks Nelly, but I’ll have to tell her straight. ‘Alice, if you’re in need of a vicar you’re to howk yourself off your backside and go see the man yourself as he won’t be coming a courting.’

Alice Dobson is a scowl of uncertainty. The last time she properly saw this man was in circumstances she finds foul to recall; the slightest backwards glance on that day and her guts knot in embarrassment and anger. She sits, legs quivering, fingers busy finding and flying from a fist. A large cameo ring, loose in its setting, rattles as she flexes her fingers, drawing attention to arthritic knuckles and wrist joints.

Angus smiles and deploys his lightest tones. ‘Unorthodox, Mrs Dobson. I could bless it, I suppose.’ He wants to add, ‘Will you stop scowling, you scary old woman.’

Alice doesn’t like the way Angus looks at her and is glad of Nelly’s company.

‘A blessing? What use is that like?’ says Nelly.

‘She’s right,’ says Alice. ‘It’ll take more than that to shift it, Vicar. Soon as the sun sets, the clattering starts up and doesn’t run out of puff ‘til strike of midnight. It’s been like that for at least two weeks, hasn’t it, Nelly? And the lads on the early shift’ll lynch us soon.’

‘Have you had the Water Board round?’ asks Angus.

‘The Water Board, the Sanitation Works: oh aye. They both took me for daft so I bid them call in at eight at night. And round they came and once the clamour started up they were off like rats. Flit. Not a second look.’

The vicar’s thinking about Bob. Alice is certain of it. He sees my wedding ring has gone. It’s long gone, vicar. Soaped and soaped and still it wouldn’t shift over these ugly owld joints.

Old Porritt, the pawnbroker, had shut forever, and this was disappointing news for Alice who knew only one shop of this kind in Newcastle and then only by reputation. Her mam and dad managed to dodge tick during the Great Depression; many a neighbour didn’t. Ticketing best clothes on a Monday, redeeming on a Friday for socials and church, then back again on Monday.

Seeking hock or sale around the Bigg Market, she turned down Pudding Chare and found a narrow old pawnbroker’s shop with a long lean window and kept by a canny lad who smiled and chatted all business like as he sawed off her wedding ring. ‘Undertakers are thieves and even if they didn’t cadge it off us, who wants to be dug up like one of them Egyptians and displayed under glass for gawkers to gander at way off in the far future? Eh?’

‘I don’t care, me,’ said Alice, thinking the lad’s ripe breath could do with a peppermint, so she decided to keep talking to stow up his gob: ‘They can dig us up and wonder at my marriage lines. I’ll leave them no proof, keep them guessing, that’s it. And believe me I’ll have no other wedding or man in this life. Sex is possing washing; I’ve gone without for so long a’m a virgin again.’

Scrap weight was the offer and she took it, a few bob and enough to buy a shoulder of lamb. My, it had tasted so good it could have come from the same sheep that grew the Golden Fleece.

‘So… so it’s the seat? The lid making the row?’ asks Angus.

‘That’s the most of it,’ Alice replies. ‘Flushes and all when it can but the cistern takes its time to fill.’

‘Don’t forget the door,’ says Nelly.

‘Well, aye,’ says Alice, ‘it slaps and flaps, but I’ve set it still with a nail in the latch. Still giddy, mind you, and works itself free every performance.’

‘And the other toilets?’ asks Angus.

‘Like what other toilets?’ says Alice.

‘In the house?’ says Angus.

Nelly laughs.

‘Well, bonny lad, you don’t much visit your parish, do you? Inside toilets? I live in Bleany Row, man, not 10 Downing Street or the Taj Mahal!’

‘Alice hinny,’ says Nelly, ‘the build them in now.’

‘Like I didn’t know that!’ Nelly, will you stop acting like a silly cow? thinks Alice. ‘I don’t live on the moon, pet. I’ve stayed in hotels and a’m not talking the types with corridor facilities. Can you imagine the Coal Board fritting out on inside sanitary plumbing? I don’t bloody think so.’

Nelly offered a nod which was good enough for Alice.

‘Other toilets along The Row, I mean, others… They’ll be on the same sewage line, surely?’ says Angus, wanting them gone.

Alice narrowed her eyes at Angus. ‘Where you taking me with that question?’

‘Tell him about the cats, Alice,’ says Nelly.

‘Nelly, he’s not interested.’

‘I told you Anglicans weren’t fass on the afterlife. Would you have it? Would you hell,’ says Nelly.

‘Ladies, please,’ says Angus. ‘What about the cats?’

‘Well, you can shift that look off your face,’ says Alice, challenging his quizzing eyebrows, rising and falling like the catches of a drunken juggler.

‘Please don’t be rude, Mrs Dobson.’ Angus crashed his brows.

‘They gather,’ says Nelly.

‘Gather?’ asks Angus.

‘Aye,’ says Nelly, dropping her voice and applying a spooky tone.

Alice knits her fingers, knowing right then Angus will rate them a pair of touched owld gimmers and turn them out his house.

‘Same time every night,’ Nelly continues, ‘round the door, on the slates, darty owld ally fighters, snags of them gawking at the netty door: transfixed. Then they start up singing…’ She loses the otherworldly voice to say: ‘Whey, if that’s what it can be called. Christ, it’s a tragic sound!’ Picking up the Halloween voice she continues: ‘Then bang, bang, bang, the spirit of the netty awakes and them cats – woosh – scatter.’ Nelly uses her hands to show Angus what scattered means.

Angus, stumped, has nothing to ask after the cat story so tries a smile.

‘Right,’ says Alice, ‘he can do nowt. Nelly, take hold of your coat.’

‘Father Kavanagh, howay Alice, he’ll listen,’ says Nelly.

‘Very well,’ says Angus, standing up. ‘As you wish. But you should know that we — and I mean Father Kavanagh and I — cannot just perform an exorcism on request.’

‘Oh, hark at him, now that he knows we’re offering business elsewhere,’ says Nelly. Even Alice thinks this is rude and gives a couple of clucks of her tongue.

‘Mrs Latimer!’ says Angus.

‘You’ve no authority over me, Vicar,’ says Nelly. ‘A’m a Catholic, but I would have thought you’d have at least helped one of your own.’

Once out of the vicar’s house, Alice says to Nelly, ‘A’m sick of holy men.’

‘Father Kavanagh’s dead canny, he’ll help, I know it.’ So keen on them seeing Father Kavanagh, Nelly catches hold of Alice’s cuff, tugging her towards the Catholic church.

Alice stops walking. ‘Molly Dawson called in when you were up seeing the vicar. She’s so sick of the noise, Nelly, she’s gotten this woman called Ruby Sanderson to call round later on.’

‘Whey, you pick your times to mention this Ruby wife! A’ mean we’re between priests, Alice!’ Nelly’s little green eyes moisten.

‘Awh, come off it, Nelly, I’d never hold owt back from you. Me mind went all addled having to see that vicar after all these years.’ Alice adds an encouraging ‘how-way’.

‘Who’s Ruby Sanderson when she’s in town?’ says Nelly, still prickled the mention of this Ruby has just dropped from the sky.

‘She’s a clairvoyant,’ says Alice.

‘What? You’re playing with fire there, pet. This Ruby’ll just encourage it,’ says Nelly, all huffy. ‘And she’ll be eyeing up all your bits and pieces in the house. Ruby? Where’s she from – the circus?’

‘No. West Denton, I think,’ says Alice.

‘Mrs Nash? Kathleen? The telephone!’ Father Kavanagh barks for his housekeeper.

Suddenly remembering the day of the week – Kathy Nash doesn’t work Friday afternoons – Father Kavanagh slaps the landing banister and makes his way down the stairs, grimacing at the telephone table in the hallway. He stops mid-flight. ‘Douglas! Douglas?’ No luck here either as his young curate is busy covering all the duties assigned to the role of the parish priest, Father Kavanagh’s workload, that is.

Oh, he was enjoying that nap! Old enough to remember when telephones were a novelty, he wishes they still were. Pointing a finger at the rattling lump of Bakelite he says, ‘Don’t you dare ring off, now you’ve dragged me from my bed!’

It was as if the machine heard the order and immediately disobeyed it. Kavanagh throws his hands to heaven and drops them with a slap on his thighs. Casting his eyes to heaven he says: ‘I suppose you think that’s funny?’

He is in the kitchen filling the kettle from the cold-water tap when the phone starts ringing again. I’ll catch you this time, you pest, he says to himself.

Stained glass windows throw reds, yellows, blues and whites across the chequered tiling, illuminating the hall like a Christmas grotto.

‘Hello, hello, St Joseph’s rectory, Father Kavanagh speaking.’

‘Ah. Good. Kavanagh, it’s Angus.’

‘And who are you, Angus, with all that familiarity?’

‘I’m fine, Kavanagh, fine. Now listen up…’

‘Not how are you, who are you?’

‘Angus Pinkney.’

‘I’m still in the dark here, Angus, my son.’

‘Reverend Pinkney of St Patrick’s Church.’

‘The one up the road? Well, good afternoon, Reverend Pinkney.’ A rare thing getting a call from the opposition. If the Anglican’s after one of those ecumenical suppers, he can forget it as Kavanagh’s bishop is dead set against what he calls limp fraternisation.

‘Erm. Quite, and good afternoon to you, Kavanagh…’

He will call me Kavanagh in the way public school nits have it, thinks Father Kavanagh. Time to nip that bonhomie in the bud. ‘Before you go on, Reverend Pinkney, you can either call me Father, which I doubt will rest well with your Anglican conscience, or Father Michael Kavanagh, or you can shorten it all to Mike. I won’t answer to plain Kavanagh.’ That was all kindly phrased, thinks Father Kavanagh.

‘Ah, sorry, Mike, in a bit of fluster you see. I’m calling to tip you off so to speak and also, erm, ask for some help.’

‘Unburden yourself, Angus,’ says Father Kavanagh and Angus duly obliges, starting with Nelly’s visit, the Dobson dilemma, and ‘…storming out to storm your walls so to speak.’

Midway through Pinkney’s monologue, Kavanagh plucks the name Nelly Latimer and dangles it like a carrot in front of the shadowy stables of his stubborn memory. Trot, trot, trot out something comes. Latimer? Latimer? Was Latimer the lass who asked if dogs have souls? It was and even back then she was old enough to know better, still, he regrets upsetting her. Latimer’s married to… to Tommy Latimer. A boy of a man with more than one bastard to his name. And Nelly Latimer? He’s damned certain it was her with the dead dog in a sack, hoping he’d go with her and say a prayer while she buried it. Kavanagh responded strong, called her a brazen halfwit and a monarch amongst the fond and touched. Said dogs died and stayed dead, done and gone and good for the soil if planting a rose bush was her business. Kavanagh was younger then, possibly still keen, ambitious, puffed up with chapter and verse. If she turned up now, whatever was in the sack would get a prayer and a blessing whether a dead dog or stillborn child. If mansions abound in the infinite multitude the Big Book promises there’s plentiful corners for spirit hounds to cock a leg and christen Christian territory. Limbo for bairns is a mean low invention, and Kavanagh’s been known to overcome the technicality of a doctor’s pronouncement of death. A man of God always knows the spark of life is something greater than the beating of a heart, or that’s what he tells the broken parents.

Nellys and Latimers, he has known hundreds of them — he needs to see a face to fit the story — and so Mike Kavanagh shoos memories back to the confusion of their byres and stalls and says to Angus, ‘Well, if you bless the old bog then so will I. And I tell you this, Angus, once word gets up the line there’ll be a holy wringer waiting for you and me. I can take a basting from my bishop, I wouldn’t last one round with your archdeacon… I need to be back for nine o’clock by the way. Pot Black’s on the telly and I’m keen to see how Fred Davis fares.’ Angus says nothing and Father Kavanagh rightly guesses the man doesn’t want to expose his ignorance. ‘I’m talking about the snooker, Angus. I’ve half a mind to send me curate Douglas down to help you. He’s younger and fitter than I am. But who am I to ruin the young fella’s career?’

Bang! Bang! Bang! Violent clashes of the knocker shake dust from the hinges of the rectory door.

‘By Christ, did you hear that? They’re heavy-handed on the knocker! Let the baggage wait, Nelly Latimer indeed! I shall stare her down. I’ve a trick with my eyes the Jesuits taught me: it’ll make her feel the fires of hell so it will!’

Angus, completely ill at ease with the idea of Catholic hell, changes tack. ‘We could meet first in the Jug, have a pint and stroll down together?’

The offer is whispered and Kavanagh supposes Angus’ wife must be about the place.

‘Apparently the performance starts at eight,’ says Angus. ‘All we need do is follow the cats.’

‘That sounds grand, Angus. Cats indeed …’

Bang! Bang! Bang!

‘Jesus, they’re braying the place down and this being Mrs Nash’s day off! Thanks for the tip-off, Angus. Seven o’clock then?’

‘Six-thirty?’ says Angus.

‘It has been a hot day, a drink would be grand. Righty, righty. Six-thirty it is.’

Ringing off, Father Kavanagh bellows at the hammering door with all the hell-fire voice he possesses. ‘Will you cease, you impatient eejits! I hear you!’

Helen Outerside makes a big deal out of polishing a pint pot, earwigging into two bookends at the bar – the fancy and the plain on their second beers, chatting deep and serious about a beset toilet – old church and new church, thick as thieves. She hears Angus say ‘ghost’ and Kavanagh repeat ‘ghost’ and next a name as blinding as a camera flash: Dobson.

It’s Helen’s dream coming to life.

Stan, as regular in bars as barnacles on the arse of a ship, walks in and announces, ‘Ruby Sanderson’s down the Rows at Alice Dobson’s house.’ Stan sports the deep pink flush of a Brown Ale drinker and sways, buffeted by an imaginary breeze, making it plain to the world he’s been up town and on the swally since noon. Stan blinks at the vicar and the priest, shakes his head and ogles them again. They’re still there. Stan moves to touch one of them, thinks better of it and moves a few steps back. This can happen sometimes with ale phantoms, the stubborn ones are best ignored.

‘Who the hell’s Ruby Sanderson?’ asks Helen.

Angus and Kavanagh stare at Stan.

‘Helen, pet, you’ve never heard of Ruby Sanderson? She’s a bill topper, hinny. Saw her at the Stolldo Theatre years back and she was bliddy electric. All them in the hall had someone dead queuing up to have word with them. It was tragically heart-warming. A mean what they had say was shite like. Divint gan oot when it’s icy and arl that patter. It was me Uncle Tommy that came to me’sell and A thought, “Fantastic, it’s race week at Newcastle!” But, hey, A divin’t kna what happens to ye when ya deed but wor Tommy didn’t gis a bliddy tip!’

Anglican looks at Catholic and Helen hears Kavanagh say, ‘So we’re joining the Music Hall, are we, Angus?’

‘What’s going on?’ Helen calls over to Angus.

‘Well, that is a good question,’ says Kavanagh to Angus.

‘Rumour of a haunted toilet, Mrs Outerside,’ says Angus.

‘Or pit gas,’ Kavanagh says, ‘is all.’

‘Yes, well, I am certainly in two minds now, Mike. A clairvoyant, really? Complete news to me and this really rather changes complexions,’ says Angus.

‘You asked me for a favour, which you’ve received, and I gave my word to those women at my door. Clairvoyant or none we cannot turn tail,’ Kavanagh’s pronouncement runs against his better judgement but if he had to confess, as confess he later would, he’d admit to a sulking curiosity to discover what was up with this toilet and wherein lay its talent for calling out the cats. If he’d heard one he’d heard a thousand confessions laying blame for personal misfortunes on the devil’s doorstep; now Kavanagh didn’t doubt evil abounded in the world, putting all down to Hell’s bidding seemed a tidy parcel to pass as he’d seen plenty mischief done by man alone. And just supposing this toilet was possessed by that grand theatrical prince of Hell, well would it not be proof Old Nick’s grand plans were thwarted by dementia?

‘You said Dobson?’ says Helen.

‘Aye, Ruby Sanderson’s doon to Alice’s yem. You must’ve heard about her beset netty, pet?’ says Stan pushing out a mighty gut as full and florid as a copperplate D.

‘No one talks to me about Alice Dobson, Stan, now do they?’ says Helen.

It’s not a question Stan wants to answer so he asks, ‘Can a have pint of McEwans, pet?’

Angus and Kavanagh finish their pints, swap nods and off out.

‘Susan,’ calls Helen, ‘mind the bar for an hour, would you love?’

Susan appears on the stair, gives her mother a twisty face and picks up a bar towel.

‘Thanks, petal,’ says Helen and makes her way to her bedroom.

She sits on an upholstered stool curtained by a red nylon valance and stares into the dressing table mirror, thinking, It must be Bob haunting the netty. And after he finishes rattling his old widow senseless, he comes up here and ruins me night’s sleep. What the hell’s he after? What if the clairvoyant can’t put him to rest? I can’t spend the rest of my life with Bob’s ghost about the bedroom: it’s taken years off me already.

Leaning closer to the mirror she inspects the surrounds of her eyes and rubs at the slight impressions of crow’s-feet with her index finger. She stops, sighs and rests her chin in the cup of her hand. Her stomach turns flighty as she responds out loud to an unspoken decision. I won’t be welcome. What if she tries to chase us away? But there’s nowt else doing. I’ll have to sort this out meself. I’ll go to Alice’s and speak direct to Bob. I’ll see what he’s after, give him a bit of comfort and tell him to bloody give over and go to his rest.

To get rid of a ghost, especially the shift of a dead lover, you have to look neat and nice. Not too gorgeous or revealing — Helen reckons this could have the opposite effect, encouraging them to stay put, forever peeping at what they were missing. She selects an ensemble she fancies he might be familiar with back in the past from one of their secret days out: a neat white gannex mac, polka dot blouse (the white one without the cleavage frills), lemon-yellow knee-length skirt, shoes matching, headscarf… but not the lovely matching handbag, she’ll leave that behind the bar. No jewellery except maybe … yes, if she can find it, that little emerald ring Bob gave her one day on the sands at Alnmouth.

Heading to Alice Dobson’s, walking down Jimmy’s Bank from the Brown Jug, she curses her choice of shoes. They’re giving her hell. It’s a steep down is Jimmy’s Bank. Down, down, shunting her toes.

Coming back up wasn’t so bad because her shoes had disappeared.

Kavanagh sees himself through his Bishop’s eyes: one of his own old priests standing shoulder to shoulder with the Anglican competition, both clasping Bibles, on the back porch of a mean little house, a galvanised bathtub hanging for a nail pressing into Kavanagh’s back. He considers unhooking the tub.

Dobson’s only means for a good soak, and thinks, Dear God, when will the Coal Board do something about the living state of these people? Eighty years ago, to live in this place might have been a privilege, the neat brick path halving the squat length of garden, one side vegetables, the other roses and some flowers, and up against the back of the yard a toilet and next to that the coalhouse, both with matching painted doors. All the bee’s knees in 1890. Now? Boiling a kettle for a wash, it’s like the living vow of Saint Francis.

Kavanagh leaves the tub on its hook and turns back to watch the unfolding farce. And if the Bishop isn’t narrowing his eyes at me because I’m playing second fiddle to an Anglican, he’s wondering what the hell is Father Kavanagh doing standing stupid as an addled donkey watching this little woman go up like Gypsy Rose Lee and waving her arms about. Sweet Jesus! Every dog is barking its guts out, there’s cats crawling over the place, and any wall that can hold an arse is sat on by scruffy little tikes and all the windows packed with dozens of dumb faces.

‘What the hell,’ says Kavanagh to Angus, ‘are we doing here?’

The air is electric and Ruby Sanderson senses a powerful being. She checks her wristwatch to make sure, Yes, five minutes to eight o’clock, the spirit is early. In Ruby’s opinion punctuality doesn’t cease being a virtue, so there’s no excuse for tardiness, none at all especially when you’re dead and have all eternity on your hands.

‘Spirit? Spirit? Come, come let me be your guide,’ says Ruby and then for the edification of the crowd: ‘The sensing. Yes. Yes. Stronger and stronger … My concentration’s being drawn away by…’ She drops her arms and opens her eyes. ‘Can you silence those bloody dogs?’

After yelps and whimpering, she closes her eyes again: ‘It’s back, now stronger, crackling, yes, something comes. Spirit?’

The cats scream a din. Meowing, high-pitched calls like the wails of a hundred hungry bairns.

‘Save your spittle, hinny. It’s not eight o’clock yet.’ Ruby identifies the voice as belonging to that dower old fishwife Latimer and ignores her.

Thump!

Ruby’s hit so hard she falls backwards. A red aura with a blue centre like a Basset’s Coconut Roll fills her vision.

‘Speak to me, speak to me!’ she says. A voice so, so far away speaks to her, ‘Out side. Out rise.’

Ruby replies, ‘We are all outside.’

‘Out. Out. Outerside, Outerside, Outerside!’

Were she here, and he’s plain glad she’s not, Lydia would be in clear hysterics by now. Embarrassed by these theatrics, Angus is all for turning home when a flush of the toilet acts like a pistol starter and the Ruby woman takes a tumble. Kavanagh stops shuffling his feet and says, ‘Sweet God.’ The toilet door shakes itself open and there, just as the mentalists had predicted, the seat and lid are gaping and slamming like a gobby hippo on the Nile.

Ruby is back on her pins and bawling, ‘Out Side!’ Then calls out: ‘Who are you, spirit?’

The toilet lid slapping ceases. Then the most astonishing sight: Ruby Sanderson levitates and shakes until a word drops out of her, ‘Bob.’ Suddenly she falls onto her backside and she yells over and over: ‘Bob. Man. Bob. Bob. Man. Bob.’

Once Alice hears ‘Outerside’ she’s fuming, and now that Bob’s dropped out of Ruby like marbles from a ripped bag she’s livid mad.

‘Bob, is it?’ Alice calls out. ‘You mithering old bugger, coming back to haunt your widow!’

It’s a good plant pot but she hoys it all the same. It flies, hits the netty cistern, and shatters, killing the geranium.

‘Bob and calling out for her, “Helen Outerside!”’ Alice looks for another pot.

Ruby scrambles past her and says all terrified, ‘Alice… Alice, he’s bloody furious.’

‘He’s bloody furious?’ says Alice, ‘Well, A’m his match, pet, I can tell you that! Get out of my privy Bob, you dirty old scum!’

A chant is taken up by a crowd of lads to the tune of Football Crazy:

‘Howay vicar, howay man! Howay vicar, howay man!’

Turning onto Havelock Street Helen Outerside sees the whole village mobbing the door of Alice Dobson’s back yard. Buggeration, she thinks, if the old cow would let me in at the front I wouldn’t be such a spectacle. She’d never let us across the threshold.

Seeing Helen, the crowds part like the sea for Moses and go all quiet as she passes them. A couple of bairns dance out in front of her saying, ‘Missus, Missus,’ pointing at Dobson’s yard until the great shovelhands of hewers come down like mist and catch hold of their kids, pulling them a-ways. A few lads quit scraping out the mortar twixt the netty’s bricks to make spyholes and just stare at Helen.

‘What the hell’s the matter? A’m not a witch, yer kna!’ says Helen.

Some wife comes up and says, ‘Missus Outerside, the ghost’s Bob Dobson and he’s asking for yer.’

‘Oh right,’ she says matter-of-factly. ‘Whey A’m here now, aren’t I.’

‘Don’t go in, pet,’ says some old biddy, glad-ragged up for the outing. ‘G’an yem, Helen.’

Helen hears herself repeat, ‘A’m here now, aren’t I.’ She never thought a heart could beat so fast, but it’s like she said, she’s here now to settle matters. And between the two she’s less scared of a ghost than Alice Dobson.

Bright as a lemon, Outerside appears in the backyard. Alice is astonished. A haunted netty is commonplace compared to this apparition. ‘How can she be here?’ she says to herself and looking round for Nelly says out loud, ‘Oh, of all the bloody audacity!’

Nelly’s eyes flit between Alice and Helen.

‘Woman, have you got no shame?’ calls Alice, who’s beginning to quiver with rage. Helen keeps her head down and walks towards the netty.

I’ll teach you to ignore me!’ Alice, set to dart down the path and pounce on the trespasser, finds she can’t move. Nelly, swift as a gun dog, catches hold of her, arms around Alice’s waist.

‘Get off us, Nelly, get off us,’ says Alice.

‘You’ll murder her,’ says Nelly.

‘Aye, a’ bloody will. Get off us!’ says Alice.

‘Divint make yersel a prisoner for the likes of her, Alice.’ Nelly’s hold is slipping fast. So she decides to jump up, placing her legs around her friend’s waist. The weight of the piggyback is too much for Alice and she falls backwards, Nelly kindly softening the blow of the brick path. No one pays attention to this pair of sixty year olds sitting stupefied after a bout of impromptu wrestling, all eyes are on what Helen Outerside’s doing.

‘That bloody netty’s gone mute,’ Nelly pants over Alice’s shoulder. ‘She’s speaking to it!’

Helen Outerside, feeling nervous and foolish at the same time, says to the toilet, ‘Bob, it’s me, Helen.’ And by way of an answer the minging old cistern plain flushed. All are transfixed by Outerside as she stands stock-still, staring into the Shanks bowl.

Father Kavanagh calls out, ‘Come away, woman!’

Helen takes no heed and steps across the netty’s threshold. Nothing happens. Then something: the door starts to shake, vibrating more and more violently as Helen talks to the bowl.

Bang.

The netty door slams shut, trapping Helen Outerside inside.

‘Lads, lads!’ an old biddy calls. ‘Get her oot! Get her oot!’

And quick as the call is raised, canny hewers are at the door with garden forks and spades, and hands wrench the stubborn thing clean open. And what did they find? Nowt. She’s gone. Clear vanished. There’s nowt in there but the pan, chain and cistern.

‘What a shite way t’gan!’ says one.

‘Enough of that tongue,’ says Kavanagh, and both the clergy are after the path, skirts flapping, digging themselves through the throng of young pit lads.

‘Picks!’ calls out Angus, and next he shouts, ‘Shovels!’

And then there’s Alice Dobson on her honkers, slapping away at her knees, laughing like a Brown Ale mazer.

‘Shout the doctor,’ says a wife.

‘Who for?’ says some nanna. ‘The bloody netty?’

The place turns hectic like the Central Station on match day, and they’re through the yard door and all over Dobson’s roses. And all the while Alice doesn’t give a toss as she’s laughing, bubbling and roaring like an old bull. Nelly’s on her feet, busy crossing herself, failing to see the comical side.

‘Haud yer whisht!’ calls out the nanna. ‘A hear something.’

Like at the needle off the record in musical statues they all stand stock still.

Bang!

Sure enough ‘Bang!’ comes again, and once more.

‘What the hell? It’s the coalhouse!’ says Kavanagh.

‘It’s padlocked,’ says Angus.

Alice stops her hilarity and is back on her feet saying, ‘If the rank waster’s shifted house he can gan darty to rot. Hey, leave me lock alone, don’t break me lock!’

Too late. A strong lad snaps off the arm of the padlock like the cap from an ale bottle. The door shunts open and out of the coalhouse like some pit canary staggers Helen Outerside. Nelly had seen a similar trick done by a Chinese magician at the Stoll Variety but this was all the more fantastical for being real. The Catholic and the Anglican grab an elbow a-piece as Helen stumbles out with bits of coal and other stuff clarting up her pretty yellow skirt and blouse.

She’s lost her shoes, thinks Nelly. Maybe you don’t need heels in hell.

Shaking her head, hair all over the place, Helen rights up her neck and says in one hell of a big voice, ‘He forgives you, Alice Dobson. He forgives you! But buy him a bliddy headstone!’

Geraniums, usually the fighting cocks of the garden, show their dry roots in the wreckage of pots. Oxeye daises and sweet peas knackered by the heat have all had their necks snapped. Size nine boots have done for the roses and women’s heels forked up the scallions. The crowds left Alice to the ruin of her garden, lifting up Helen Outerside like ancient royalty in a Cecil B. DeMille motion picture. Out, out, and up Jimmy’s Bank, mobs of them hooking on for a free hand-out at the Brown Jug. Hoping for a longer stronger draft than a gill of Barr’s lemonade.

Helen might call for drinks all round, thinks Alice, but that bag lass of hers, the beautiful Susan, will see they pay for it.

They’ve all gone to the Jug and Alice thinks that’s fair enough, her netty’s given most of them hell on earth for days on end and tonight they received their wages, compensation, a big free finale to all the banging and clanging they’ve put up with. A gawk, a gob, a good owld neb, and enough excitement to keep them gabbing forever. And on that score she’ll have to do something with the netty, have it torn down or something, otherwise the kids’ll be in and out daring themselves on to meet the ghost, she’ll never have peace. Mind you, if its pulled down she’d be back to piss pots and the like, aye a netty’s needed after all.

Sorting out a Saxa salt carton and a bottle of pale ale in the scullery, she says to herself, Alice pet, you should’ve moved away years ago. Aye, if only football pools had came in.

Taking up the salt and beer, she walks down the garden path, kicking clumps of earth that puff into dust on contact with her shoe. She’ll take a broom to it all tomorrow.

It’s a canny night, warm but not stifling. There’s a moon and the stars are starting to show. Number 25 flicks the telly on, she hasn’t drawn her curtains being always nebby. Number 27’s all dark. That lot’ll be at the Jug, anywhere for free little green apples, them.

No Nelly, thinks Alice, feeling a bit odd, not having Nelly about. Whey, Nelly’s Nelly. She’ll be at the Jug I expect, saying owt that gets an audience. That’s her style, she needs a bit of comfort and if it comes from being noticed, well, she deserves it. Laugh at her, they all do and I’m glad she cannit see it. Not that they’d laugh at her in my company. Poor owld Nell, she’d wade into the Tyne if she had the slightest inkling.

Oh! The door’s all crook, the sackless bastards have snapped a hinge. I’ll get Dawson to fix it like he did last time. Ha! Last time it was wrecked getting Bob’s body out of there. Right. Matches.

Alice lights a candle and sees half a dozen lost ants. ‘Away to your mother,’ she says and they shift, then, ‘Hello! A spider’s back in? A’m getting the measure straight and crooked here. Bob?’

A little bubble breaks in the toilet bowl.

Dark’s coming on, so Alice drags the netty door closed. The candles going canny and she does what she’s been holding on to do since noon. She doesn’t flush.

‘Bob?’

Considering posh, soft tissue a waste of money, the telly page of the Evening Chronicle seeps up the water, grows heavy and sinks down like a lid.

‘Bob?’

She knows her man is hiding round the bend.

‘Bob? You could of come in, you know. Your old chair’s still nigh the fire. So you don’t fancy that?’

More bubbles flapped about the scrap of the Chronicle.

‘Mind but you’re timid now, aren’t you?’

They’re making these cartons too clever, she thinks. Managing to thumbnail out the chute she empties the salt down the toilet bowl.

‘Bob? Bob?’

It starts to boil with bubbles. Bob’s caught sniff of what’s up.

Alice says a few words, the ones her mam’s mam taught her, words netted on the winds of mountain passes, words older than the pyramids and fearful to the pharaohs, words known to Solomon to catch the djinn and stopper their badness in lamps and bottles.

Alice snaps off the cap of the bottle of pale ale. She takes a draught. Thinking of them drinking at the Jug has made her parched, and those old words are hot and dry. She upends what’s left in the bottle, sending it to meet the salt, saying out loud the last of the old words.

Taking up the candle which has no meaning other than giving a bit light, she says to the netty, ‘Love gives you nowt and you can sit nigh the door all your life waiting for the sneck to click and be prompt up to serve out his tea. And as you’re waiting you check a framed snap of you and your man taken somewhere nice on a happy day and say to your stupid self, aren’t we unique. But, it’s all shite. It took you to die to teach me this, and all of them, all of them from the Rows knew what a deception it was. You humiliated me back then, bonny lad. And you’ve come back and done it again, making a spectacle of me and your fancy woman Outerside. Did you think it was clever like, that you’d get your way haunting a widow’s netty for the sake of a headstone? You’ve obviously forgotten all about me, pet; being dead has turned you daft. No headstone for you, hinny. No, you’ll lie in the style you lived life: unknown. You’ll have cottoned on by now that I’ve tied your rotten spirit fast to the sewerage system? Whey it was your idea in first place, I’ll grant you that, and this is what you get for thinking yerself a clever bugger. Off with you now, go turn your hand at menacing the netties of The Brown Jug. And if you show up down here again, and hark on this, Bob Dobson, I’ll never release you. So off to your bloody fancy woman and what a crying shame that is for her.’

And with that Alice pulled the chain and watched old news flush away.

Would love to see more stories? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.