The Ghosts from Kathmandu

Leena had to starve herself for three months, but eventually her figure is boyish as his. She exercises in secret, locking her fingers over the beam above the kitchen doorframe and hauling herself up until her arms burn and her stomach muscles shake. As Anuj wastes slowly into bone and mattress, she grows lean and wiry and capable.

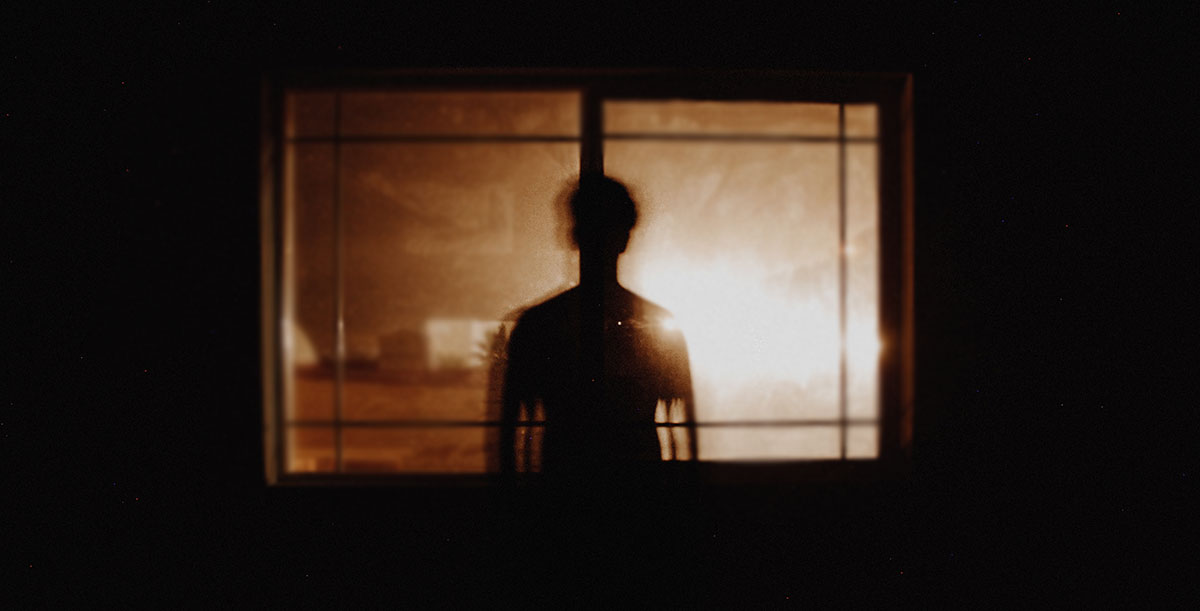

In the evenings, when they eat together, she observes her husband closely, and marks the rhythm of his right hand as it balls his rice to bring it to his lips. She practises mimicking his voice: the longer vowels, the softness of his tongue rolling in his mouth. His laugh she has to summon from memory, and she rehearses it in front of the mirror while he sleeps, standing naked except for one of his long shirts, her hair tucked down inside the collar. She drops her breath into her stomach and lets it deepen there. She winks, and the young man in the mirror winks back. She presses her lips to his and breathes her life against the glass. It is hot and youthful and impatient.

The Tourists have been in town for eight days. Leena watches from the window as they emerge from The Kathmandu Guesthouse a little later each morning, outrageously tipping the rickshaw drivers who disperse them amongst the back-packers and the gap year students. They have a sight-seeing itinerary, although they take no pictures. Their fingers twitch in the remembered habits of phones and laptops. They compose tweets that nobody will ever read; they overlay the Buddhist stupas with imagined Instagram filters. Nashville. Gotham. Vintage. It’s all so new for them, this withdrawal from the world. To Leena, they look like big, bright school children.

Their tour guide, pink and shining in his polyester shirt, is an easy man to watch. They do not know his name; know nothing except that he will go last. He moves steadily between internet cafés, his phone buzzing in his pocket. He is Norwegian, perhaps, or Dutch, but he answers in an American accent:

‘Namaste. How are you?’

Back at the house, they never answer phone calls. Each day, a note arrives for Anuj and he and Leena reply to it together. At first, he writes himself and has her copy it, careful to match the spikiness of his English lettering.

‘I’m glad you are enjoying your visit. Will you go to the zoo tomorrow? I think you would like to see the mad bear! ’

‘I hope the food at the hotel is to your liking. If not, you must come for dinner with my family. I have told them all about you.’

She signs her husband’s name, over and over, until she dreams about it.

Each day, the rickshaws return one fewer passenger to the guesthouse, and another room becomes available. Their clean sheets are hung to dry over the balconies like flags, and taken in again before the rain comes.

In the mornings, Anuj plots the Tourists’ journeys. Leena brings his maps to him in bed and he shows her all his favourites: the bold red lines that mark the routes most difficult to track.

‘India,’ he tells her. ‘You can fly direct to New Zealand now. Get a job as a surfing instructor, see? No one bothers you. That’s one year, maybe two.’ She nods.

The map in front of Leena has a jagged strip torn out of it. The whole route from Greece across to Pakistan has gaping holes in it. Syria is gone completely.

‘We used to use that one a lot,’ says Anuj. ‘Much harder than when we lost Japan. You’ll learn to change your habits quickly. Now you try.’

She takes the next name on the list. ‘Singapore,’ she says, stroking its shape. ‘To visit friends?’

He takes the ledger from her and scrutinises the name. ‘Not for this guy,’ he says, his brow furrowed. The weight of the world on him. ‘We could start with a trek here in Nepal, maybe, to buy some time. Could try Tibet, although it’s risky. But he needs a destination fast.’

He gasps, his slight chest heaving. His skin is pale and waxy. Leena lies beside him, not an ounce of flesh between them, and they talk their grand plan through again from start to finish. She reels off the names of the men in his photographs, the names of their wives, their children, and the facts comfort them both. She measures her hand span against his, and takes stock of the distance she will have to travel.

She is learning fast. Some days she feels that calm anticipation replace her fear, ready to shake off the waiting. She shape-shifts between her old identity and her new one, some days more comfortable as a boy than as a wife. She notices the small differences: her laugh is louder, and she makes more eye contact with strangers. Only her mother-in-law’s forceful intrusions keep her strung tight as a hare.

‘Look at you,’ she mutters to Anuj, on her twice-daily visits to their bedroom. Nice and loud for Leena’s benefit. He lies there weakly and lets her chatter away to him like an infant.

‘You’re not very comfortable like that, are you, babu?’ she asks, not waiting for an answer. ‘Shall we ask Leena to help you sit up properly?’

Leena does as she is bidden, quiet and quick, and bites her tongue until there’s blood in her mouth.

In the afternoons, Anuj plans the final disappearances. They are for the Tourists who will not come back; the ones for whom a few years to be forgotten will not be enough. Leena knows never to ask why these people need to disappear. Their business is in the vanishing; they are not detectives.

‘Don’t be afraid to get creative,’ Anuj says. She likes this part. The pen keeps slipping from his hand, so she writes for him.

‘Ready?’

He groans and puts his hands over his swollen eyes. ‘Moped accident. Broken neck. Find a body if we need to.’

She scribbles. ‘Next?’

‘Secret illness. Wanted to see Russia one last time. Overdose… Wait, no. We did that one in Sweden. Better die of natural causes. We need another local one.’

‘I know. The zoo – the mad bear escapes and eats him.’

He grins at her. ‘Perfect.’

It’s a blessing that he feels a little better when the Ghost arrives. She is shown inside before she can attract attention, before an old man passing by, who might be anyone, could see her and report it.

Anuj struggles to his feet, and washes deathbed sickness from his face and hands before he goes to greet her. His mother fusses, but the urgency is obvious, even to her. Ghosts bring trouble, and they must be dealt with.

The Ghost is a woman, no older than Leena, with a tight, hungry mouth. Her presence in the house feels contaminating. Her look at them is too pleading, her helplessness too obvious. She reaches out a hand in greeting and Leena shrinks away, pressing her palms to her heart instead.

‘Namaste.’

She has forgotten to put her nose ring in, but the Ghost is a westerner, and will not notice.

Anuj offers her a seat. He keeps his expression severe and unreadable, and rests his hands on his knees to hide the shaking. Leena serves their tea and listens from the kitchen.

‘I’ve changed my mind,’ the Ghost is saying. Her fair hair is dirty and her eyes are wild.

‘You can’t. You’re off the map now.’

‘Put me back on it, then!’

‘We don’t do that.’

‘Please,’ she says. ‘You have to help me. My parents are getting old. I want to see them. I want to go home.’

The room is quiet for a moment. Leena puts her eye to the gap in the curtain; the Ghost is pulling out a mobile phone. An old-style Nokia. Pay-as-you-go. No internet, no apps, but still.

‘Are you mad?’ says Anuj. He snatches it from her, and in one quick motion he has cracked it open, gutted it, and crushed the SIM card with his teeth. ‘No. Never.’

‘I thought I could just contact them. I could see… how things are. If there was any chance – ’

‘No chance. You think they will not find you if you use these things? No chance at all.’

The Ghost stares at the remains of the Nokia. ‘But how am I supposed to live?’ Her voice trembles. ‘What do they do – all these people you make disappear? No phone, no name, no passport – where do they go?’

Anuj sighs. The sound rattles. ‘We do not ask that. We do not even think it. We vanish them – they don’t come back.’

‘But don’t you understand…?’

‘My older brother died. I understand. It was hard, but he did not come back. People like you. They don’t exist.’

‘But I do exist,’ she murmurs, close to tears. ‘I’m here.’

‘You shouldn’t be.’ Leena hears their chairs scraping. Time to go.

They wait for the rain to send her on her way. In the deafening sound of the downpour, her footsteps might as well be silent.

Kathmandu Guest House empties, one day at a time. When the time comes, Anuj wants to cut her hair himself. Insists on it, lip trembling like a sulky child, so she props him up on pillows until he can sit upright, and crouches in between his knees. Outside, the roads are like rivers; the dust turned liquid, licking at their doorstep. Their room absorbs the thick, hot damp of August.

Leena listens to the scraaape, scrrraaaape of the scissors with a sense that he is shearing someone else. Dark tufts tumbling to rest on the pale bedspread. She turns to him, eyes bright, resisting the mirror.

‘How do I look, Anuj?’

‘Very sweet, bhai,’ he tells her. Little brother. His teasing smile is almost able to reach his eyes. ‘Come here, babu.’

They make love tentatively, him clumsy with the new shape of her. She wonders where he finds the energy. Beneath her, his ribcage feels fragile as a bird’s. She dips her tongue into the space between his collarbones and thinks, Remember this.

‘Don’t get sick,’ he says, half-hopeful.

She still smells of him as she pulls on his shirt, his trousers, his narrow-waisted belt. The shoes she had to buy, pretending they were for her nephew, gleam like hair oil. He catches her by the wrist, his grip like a moth-wing, and she fights the urge to brush him off.

‘Are you ready, Leena?’

She nods. The upward-only jerk of her head, like he does, like his older brother used to.

‘Because he’s never met me,’ he says, ‘there’s no reason for him to think anything is wrong.’

‘I’m not afraid.’

‘I’m afraid for you.’

She plants a rough kiss on his forehead, her eyes darting to the clock.

‘I’ve got to go.’

‘Show me the signature again,’ he says, clawing at the moment. ‘Practise. Here, on my arm.’

He rolls up his sleeve. His wasted flesh is tinged with yellow. Through his shirt, even, she can feel him burning.

‘No,’ she says. ‘There isn’t time.’

She tries to pull away from him, but he clings to her arm. With painful effort, he rolls himself half over, reaching for his watch; his fine gold watch, with his initials etched onto the flipside of its face. It fits her wrist better than his own.

The rain has stopped by the time Leena steps outside, but her trousers are quickly hemmed in crimson mud. It’s only a short walk across the city but she takes a taxi, thrilled by the freedom of it, her bare arm out of the window to shoo away the boys that come to tap against the windscreen. She rests the rucksack loosely on her lap, and shrugs it on again when they reach the shop: no big deal. In it, the details of a new story, a man who found religion here, gave up his name and all his worldly goods, became a monk and died a natural death. An easy fix, no passport needed. A nice, round tale. A Ghost created.

Two beggars crouch at the side of the road, a few metres apart; a man with no shirt and deep-set eyes that linger on her, and a woman in a pale yellow sari, with a tiny baby strapped against her chest. The air conditioning hisses at her as she approaches. The man has a look of her husband about him, she realises. Something familiar, something haunted in the shadows of his face. He crouches with his elbows on his knees, the way that Anuj does, the way his older brother used to. Leena lets her spine relax. Inhales. The beggars watch her.

The shopkeeper is talking to a Tourist in the doorway, looking strained. It is a souvenir shop, he explains, with fixed prices. The Tourist haggles anyway. He is the man from the internet cafés, the large, pink man with short fair hair, his chin protruding. The Tour Guide is always the last one to go, and the deal is always done in person.

‘How much for this?’ he asks. American accent. He is shown the price tag, marked in euros and dollars.

‘Alright. How much for three?’

The shopkeeper holds his hands up in front of him, despairing.

‘It is the same,’ he says. The Tourist frowns, his pale eyes disappearing in his rosy face. He points at Leena.

‘How much if he was buying, eh?’

‘The same, the same.’

‘Like hell it would be.’

‘Sir, I cannot change the prices. Do you want to pay now?’ The Tourist shrugs.

‘I think I’ll look around a little longer.’

The shopkeeper grimaces, and backs away. He looks past Leena to the street outside, where the beggars look on with interest.

‘Again!’ he shouts at Leena. ‘You see them? Every day I move them on, and here they are again!’

Furious, he marches off, to return a moment later with a bucket of water. He tips the entirety of it over the woman’s head, soaking her. Her baby screams.

‘Hey!’ The Tourist thunders over. ‘What the fuck do you think you’re doing?’

On the doorstep, Leena puts down her rucksack. No big deal. The Tourist has his big red hand on the shopkeeper’s chest; the man looks terrified.

‘I told her!’ he says, his voice shaking. ‘I told her yesterday, come back here and I’ll beat you. She brings the child so I cannot beat her!’

The Tourist looks about to hit him, and Leena digs her nails into the palms of her hands. A man on the brink of vanishing could be unpredictable, she guesses. But instead, he pulls out his wallet and waves a handful of notes in the shopkeeper’s face.

‘This is your apology,’ he says.

He picks up Leena’s rucksack like it is his own and throws it over one large shoulder. He gives the money to the beggar woman, who takes it silently. She staggers another metre down the street, and crouches again. The Tourist walks away, and does not look back.

The shopkeeper rolls his eyes towards the heavens.

‘You see, brother?’ he says to Leena. ‘You see what I have to put up with?’

He goes inside. Leena takes the money from the beggar woman and signs the receipt, quick and easy, just like her husband. She hails a taxi home. The shirtless man watches her leave, his gaze bold. She feels as though his eyes burn through her clothes.

When she returns, she takes the money up to Anuj and she sees that he is dead.

She makes ready. She lays out his best clothes for him, and in between her letters she keeps vigil.

‘My wife has passed away. I will be staying with my family in Pokhara. Please send all future correspondence there.’

The disappearances continue at the same, steady rate. Outside the city, the air is fat and fragrant. She sits at the table with the windows flung wide open while she works. In the mornings, she plans the Tourists’ journeys. When a destination fails, she tears the map. The world shrinks under her hands as the letters keep arriving.

The partners visit her, of course, to see that the business is in safe hands after another family tragedy. She remembers the death of her brother-in-law, eight years earlier. The sudden change of authority, the new lines on her husband’s face. But he handled it. He kept the people moving, as his family always had. The journeys were plotted, the stories delivered, the fees collected. Ghosts had rarely reappeared, and they posed no major threats. There was a rhythm to this work and it had suited him. The partners and their families relaxed. Stopped eyeing up their own sons, readying.

‘My story is going to outlive me,’ Anuj had said to her, the week before he died.

She commands the household now, and her mother-in-law, who knows, but will not notice, is stiff and silent. Leena shrouds herself inside his second-best suit. She feels bigger in it than she’s felt for months; no more shrinking inside the glowing silk of her own clothes. Her waist opens. Her walk loosens. The arches of her feet relax.

Below, the murmur of her guests gathering. She goes down, and she plays the grieving husband. She wears Anuj like a coat in winter, his wedding ring warm and loose on her right thumb, his initials listening to her fierce pulse. Flesh of my flesh.

‘So sad,’ she hears Aamar quote. ‘She nursed him and she died so quickly. She was a good wife to him, but she must not have had his strength.’

The men nod, their faces grave. They are dressed expensively; they eat Aamar’s cooking with sombre enthusiasm.

She does not think of his small body, quiet now where hers should be. She does not think of the alternative, of the shirtless man whose face was like his brother’s, she does not hope.

She shakes the hands of all these men, and looks them in the eye. She smiles, and they say,

‘It is so good to see you, looking so well.’

Subscribe to our weekly Fairlight Flash newsletter for short story and blog updates