To Be Loved, and Made Twice

Disquiet. Squirming, urgent agency: this moment is unbearable.

The doorman, Bernie, has hastily shoved everyone out at exactly 2am as he always does, his fervent protection of me and the other Gordie’s staff, and of his own anticipated bedtime. It’s 2.05 now. Through the padded door, you can hear the multitude of muffled voices coming from our recently evacuated patrons. Too-loud laughter over cigarettes and giggling girls arguing over who is going to app-order the ride home this time. It is usually background noise to me, but tonight I find myself startle-flinching at each rise in the volume of their drunken banter.

Mechanically I sweep empties and half-empties off of counters and tables into sticky black bins while Vera sweeps and Tanner’s got the sink running. I’m silent. Normally the three of us would be sleepily chattering through our final tasks of the shift, mildly cheerful and grateful for the revealing last-call lights that actually allow us to see what we’re fucking doing for the first time all night, while simultaneously squinting in response to their comparative harshness. My colleagues don’t seem to notice I’m not joining them in their happy-hour carolling, which saves me a moment to wallow in my shock.

Bernie lets out a belting smoker’s cough and wheezes a little as he locks the front door behind him and shuffles over to join us. The bar staff always go out the back door when we leave. I suppose Gordie’s owners decided this is how we’d do things some thirty years ago when they made their incontestable permanent decisions on how their bar would be run. I’ve heard someone say they think it’s safer.

Safer. My stomach churns as I realise I’m about to go home in the dark. Alone. It’s something I do every night. Before, I’d become so accustomed to my late-night bar shift that I had felt I’d befriended the dark, but the disquiet – no, downright fear – in me has plastered to my nightly routine a new dread and alarm. Here I am: a forty-five-year-old, tough-mannered beer pourer, as gleefully unfeminine in personality as God makes women (I’ve been called ‘butch’ and said ‘thank you, but my name is actually Lora’), who’s had nearly fifteen years of experience being awake at night, plus another five years of being and living alone – feeling afraid of being alone. Feeling afraid of the dark.

And it’s not that there’s a particular face of threat that I’ve suddenly discovered is awaiting me in that lonesome dark. There’s no concrete person or entity occupying my new frame of fear. No. It’s simply the disquiet within me, as abstract and verbally intangible as the definition of the word ‘the’. So what has conjured such disquiet? Even I want to deny that something not inherently threatening could make me feel so childishly afraid and laugh it off, but I can’t. Something’s got in my head.

It started with Sam.

Sam is a handsome twenty-something. Windswept hair, clever eyes, a dimple on one cheek, a fountain pen always behind the opposite ear. His face is just childish enough to tug at your sympathy, while the evenly distributed dark scruff on his cheeks and chin suggest that, not only could he grow a full beard if he wanted to, he’s old enough that building a mothering Oedipal complex over him would just be… inappropriate. I’m not a goddamn senior citizen after all.

Sam started coming to Gordie’s a year or two ago. I can’t really pinpoint exactly when it was, but what I can tell you is that the first time he walked in the door, he instantly became a regular.

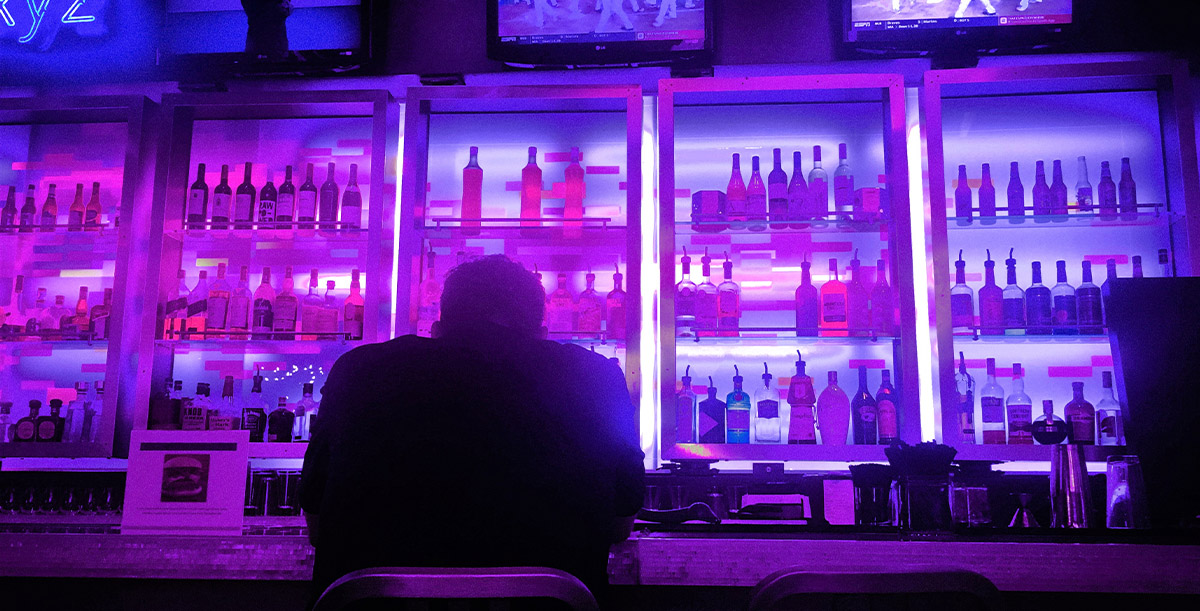

Gordie’s isn’t a large bar, nor is it anything remotely special. It’s a forgettable, trashy dive bar in a college town. Wooden floors, wooden walls, wooden bar, wooden stools. Green lighting, green pool tables, green beer once a year (fuck it, it sells), and a green jukebox. The jukebox never plays very loudly, even though someone’s always throwing quarters at it to make sure it never stops weakly croaking out jam band noise. I’m telling you these boring details because the bar is small enough, the jukebox quiet enough, that if you really tried, you could hear pretty much any conversation going on in that room. But why would you try? As I told you, it’s a blatantly unoriginal place, with unoriginal people as its patrons, 90% of whom are new-to-town state university kids who’ll order a shit drink, look around like they’re on a field trip to a museum, find a better bar to frequent without much trouble, and then never come back. The other 10% are the much older locals, the dedicated regulars, the mediocre booze worshippers. You’d have to be as bored as the eighteenth century to make an effort to eavesdrop on the hum-buzzing conversations of Gordie’s.

Here’s the kicker: I am always that bored.

The most complicated drink we’ll make in Gordie’s is a gin and tonic, with the pinched slice of lime setting it a step above a Jack ’n‘ Coke. You could say my job leaves me wanting for… everything. So, yes, in the moments I’m not listening to your drink order, I’m eavesdropping on your conversation. I’ve even made a game of it. Decide which participant I side with the most in any conversation, and who is the ultimate antagonist. I almost always share these details with Vera and sometimes we’ll debate the moral quality of someone’s character based solely on their opinion of a professor we don’t know, or insistence that a certain grocery store has a great beer selection, or lament of oh-my-god-there’s-nowhere-to-park-on-campus.

The first night Sam came in, I decided pretty quickly he was the antagonist of antagonists. He came in alone. Which, trust me, can mean only a few things: (a) trouble-starter, (b) needs a fuck, (c) just had the worst day in history, or (d) devoted alcoholic. This had me watching him immediately, preparing to take an educated guess at which he fell under, hoping he wouldn’t be an (a). I lose out on a lot of tips calling the cops and Bernie’s too asthmatic and soft to be as tough as his stature might otherwise indicate.

Sam ordered a pale ale, asked for a goddamn straw. Now all of the Gordie’s staff were watching him, thinking Who’s this little shit? Vera muttered: ‘Edgy little schoolboy, huh Lore?’ and giggled at my appreciative glance in her direction.

Passing him his beer (and straw!) with a smile I hoped he could read as condescending, I released him into the wild. And Sam didn’t waste a fucking minute. He set his eyes on a couple of university girls, walked right up to them and flashed a blindingly unforgettable grin that should’ve belonged to an Ivy League trust fund kid. I immediately pegged him as a (b) needs a fuck, and lost a little interest.

But Sam didn’t disappoint for long. He introduced himself; the girls’ smiling responses said ‘you’re too good-looking to creep us out; you may state your case’. And he fucking did, his cunning smile never fading.

‘Do you ever think about death?’

This surprised me. What’s this asshole going for? I tried to fill in the blanks, no longer finding him quite as predictable as he’d initially seemed, though still entirely unable to give him any credit for originality.

One girl’s smile of welcome faded a little. I saw a wave of confusion pass over her heart-shaped face. The other one, though, holding up her IPA like a scythe and attempting to match his grin, thought this was bait worth taking.

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘Who doesn’t?’

He smiled a little wider, eyes fixed on her, his hooked fish.

Okay then, it’s a prank, I thought.

‘What do you think about, when you think about death? What does it make you feel?’ His voice was breathy, lightly caressing the words as they left his mouth.

Okay then, he’s a psych major who hasn’t even started classes but thinks he’s an intellectual revolutionary, I thought.

He winked at her.

And that’s how he thinks he’ll get pussy, I thought. (B) is my final answer.

The girl he’d hooked leaned in. ‘Well, I don’t believe in God,’ she said boldly, like it was a brave statement she could still be strung up by her neck for, ‘so I think you just… stop existing. And return to the earth from whence you came.’ She gestured airily around her, self-appointed bohemian princess.

The other girl, the one with the heart-shaped face, fumbled with her necklace. A cross, I bet.

Sam noticed. He turned to heart face. He hadn’t given up; catch all the fish. ‘How does that make you feel, then?’

Okay then, he’s a sociopath, I thought.

She pursed her lips, fingered the tiny straw in her vodka cran. ‘Oh, I don’t know. I’m not worried about death… you know, yet?’

‘It doesn’t scare you?’ he feigned surprise.

‘It doesn’t scare me,’ his first fish flopped, striving for his returned attention. ‘I think it’s beautiful.’

Sam started drinking his beer then. He took several large gulps from the glass itself, putting down at least a third of the pint, before deliberately (almost theatrically) sticking the straw in his mouth and sucking the drink past its halfway point.

Boho fish giggled. ‘Isn’t that a beer? What’s with the straw?’

And like a thunderclap, the spell was broken. Sam’s smile disappeared. And on his blank face I read a million dark words. I thought for a split second he was going to burst into anger; I even worried he was edging toward dangerous for that tiny moment, ready to drop his needs-a-fuck persona and dive straight into trouble-starter. But no, he smiled again, a new smile. No knowing look this time, no flirty sly. He was polite. He thanked them, shook their hands again, and told them he hoped they’d have a fun night.

They both looked a little surprised – then a little disappointed – as he sauntered off. He stood at the bar, one arm on it, and finished his beer at a moderate pace. After setting his glass down, he removed the pen from behind his ear and hastily wrote something I wished I could see on his wrist, then walked out.

Vera, towel hand in a glass, bid him goodbye. She looked at me then with teasing eyes, interpreting whatever downtrodden slump my face had taken on as total disgust and ready to tell me I was overjudging and debate me on my usual moral character read. ‘Well that was anticlimactic,’ she clichéd.

I shrugged. Something about the situation didn’t make me want to laugh. It left me feeling like I’d been denied something I was owed. I can’t really explain that feeling, but I can tell you that mysteries are only unbearable when you think you ought to own the answer. I’m not sure why I felt the truth belonged to me, but from then on, my eyes were out for Sam – an eternal watch.

Sam didn’t make me wait.

He came back every single night thereafter and his five-act play did not change. It soon became routine. Sam would arrive around the peak of the night when Gordie’s was at its fullest, which would change depending on the day of the week or if it was a holiday. He’d order his godforsaken beer-with-straw, pick someone in the bar to pose his favourite question to, finish his drink while scribbling on his wrist… and then leave. He always tipped a dollar, always carried a pen behind his ear, always entered into a conversation with that undeniably bright grin. That Trojan horse of a smile never failed to gain him entry into any social starter and he’d roll right in.

And then ‘Do you think about death?’ would spring on out.

And it was always met with surprise, because Sam never spoke to anyone who was a regular or staff. He’d pick someone each time who, regardless of sex or race or (arguably) attractiveness, he somehow could tell was at least fairly new or irregular enough to the bar and probably hadn’t noticed him before. I am not sure what earned him this ability aside from skilful observation, but he seemed an expert in his choosing. It wasn’t for a month or so that I started noticing an additional trend: no one he talked to ever seemed to come back. But that didn’t seem to me much of a surprise and more a continued reflection of the nature of the bar and its social status, which clashed with that of the primarily white and moderately privileged students who occupied the town.

The regulars of course caught on. A number of instances, Sam was mockingly clapped on the back, a chortled beer burp spraying his face with ‘That’s quide a piggup line you got there. How often duzzit work?’

Or a generally curious and friendly post-vodka-soda-gulp comment of ‘Did you ever get the answer you were looking for, darling?’

But Sam isn’t looking for a particular answer. At least that’s what I’ve come to believe. That, for Sam, this is sport. The same move made every day on the same board by the same piece: an eyeroll mockery plastered on a cunning grin, the groaning cliché of taking something seriously and turning it into a game. Sport. And the win is simply his own participation. There is no half-time, no score. The game in itself is an ongoing victory. And you can tell he feels that way from how his eyes light up before you’ve even given him an answer. A little sparkle in those pupils. If you look closely, you might see a jersey-clad superstar leaping into the air and shouting ‘GOOOOOOAL!’

But no one looks at Sam this closely. Except, well, me I suppose. And even then, I still haven’t found the answer I’ve been looking for in him, the simple question ever playing in my head. What is he doing? What is the straw about? What is he writing on his hand? What is his goddamn, motherfucking DEAL? My continued confusion blended with frustration eventually became an increasingly poorly veiled rage crackling inside me. I came to fucking hate Sam. And while I am an emotionally private person with a generally stoic face, Vera and the other staff caught on to my feelings. While they found it amusing that some stupid kid had gotten to me so, they were protective of me and of their tips. And so they’d always jump to serve Sam while I fumed at the other end of the bar, wishing him all colours of death.

But you can grow used to anything, even things that really piss you off. Anger has two places it can go. It can either volcano out or harden into cold, rocky resentment within. Naturally, I chose rock over lava. It is, at least, certainly the female thing to do.

That rock sat heavy within me for a year or so. I’d given up on finding out what Sam’s deal was. In fact, I didn’t think he had much of one at all, just some weird social complex whose remaining flicker of interesting had been snuffed out long ago. Most nights I’d tune him out, but once in a while I’d check back in to see that – nope, he hadn’t changed his game at all. It wasn’t until recently that he’d re-sparked my attention.

The bar was absolutely dead. It was the deadest I’d seen it in years, even for a Monday. I leaned against the back of the bar, appreciating the moment of peace. We only had three patrons at the moment, all regulars, and two of them had gone out for a smoke. The remaining patron was one of our oldest regulars, a retired professor named Cormac with a depressed demeanour and a perpetual spray of white stubble covering half his face. I watched him as he swayed slightly in front of the jukebox, clumsily poking its buttons.

‘How you doing, Cormie?’ Vera asked as she cleared a couple of glasses from a table nearby.

‘Ask me after a few more of these,’ he said, holding up his glass. The cheapest rum that pocket change could buy spilled a little with his gesture. ‘In fact, why waste time? Just replicate this about three times over and I’ll be feeling much better.’

‘Nah ah. You know the drill,’ Vera scolded.

The drill she was referring to was a set of rules we enforced on all of our alcoholic regulars. Walk across the bar to the jukebox and back once you’ve emptied your drink, and sure, you can have another one. If you so much as stumble, you get coffee. Finish a cup of that, and you can audition again. Vera employed the rules with such a loving sense of motherhood that the patrons really never argued with her, at least beyond the playful remark that she ought to just dump the bottle right down their throats. I think she made them feel cared for in the one place they really felt at home and that was enough for them not to fight her on it.

Cormac’s song crackled out of the jukebox speakers and he walked a curvy line back to his usual seat at the corner of the bar.

I smiled at him. He was one of the few people in life I thought was worth smiling at. Despite the intellectually charged unhappiness he wore like a battle scar (‘I’ve earned my misery; I found it in a book somewhere,’ he once told me), I found him to be a genuinely kind man who really didn’t want to hurt anyone, besides – I suppose – his own liver. I’d also taken one of his literature courses back before he retired. Back before I dropped out of school and unknowingly resigned myself to working here for the rest of my life…

He returned my gaze, his signature thousand-toed crow’s feet smile filling me with a sense of patriarchal nostalgia. I bet my dad would’ve enjoyed having a drink with him, I thought. And then snapped out of that as he said something that caught me off guard.

‘You think Sam will make it over here tonight?’

I blinked. Cormac was probably the only regular who hadn’t participated in the gossip when Sam first became a Gordie’s hit, but even that gossip had died out by this point.

‘He’s here every night, man,’ Tanner said as he changed out a keg nearby.

Cormac didn’t even look in Tanner’s direction. He was looking into my eyes as if awaiting my answer specifically.

‘Well, yeah. He always shows.’ I twitched a small shrug.

Cormac nearly cut me off, his sentence flying out before I finished my last word: ‘I think he’s up to something.’

‘You think so?’

Cormac’s eyes sparkled. ‘I followed him last night.’

There was a series of scrapes and thuds as Vera, Tanner and I shifted in shock, our undivided attention now fixated on him. I felt my heart rate increase, a million suddenly unearthed and zombified questions clambering up my throat to eat his brain.

But before Cormac could indulge me, a dozen plus rowdy male students burst into the bar, filling it with a chorus of laughter and jabbing words. There was a healthy mix of fraternity types and apparent athletes in uniform and their energy level indicated pointed excitement: they were celebrating something. And judging by their tactile body language, Gordie’s wasn’t their first or second stop of the night.

Their bodies hit the bar like a storm wave against a pier. We rallied and took drink orders. I whined internally, a kid awakened and forced out of bed just when her dream was getting interesting. This complaint rose to a tantrum level as, to my utter horror, Cormac slapped down a crinkled bill and slunk out. Fuck! I screamed silently. Fuck! over and over, The Great Volcano Sam emitting a reborn rumble within me, threatening to boil over once more. Fuck you, Cormac!

And, as if summoned by my internal chant of fury, Sam appeared at the door.

He approached the bar and waited patiently for a gap in the party men. Vera poured a multitude of shots and I bent down to grab fourteen PBR tall cans from the fridges below, one for each guy, resentment building with each can. Sam finally squeezed in and I listened with a renewed sense of urgent fascination as Tanner approached him.

As I stood up and began ferrying beers out to the noisy boys, I caught a glint of stunned awkwardness in Tanner’s eye as he stuttered a few times before successfully asking Sam if he wanted the usual.

‘Yes, thanks,’ Sam said, as casually as always.

Tanner glanced at me, lips tight and eyes lit with the kind of anxiety that can only come from unresolved curiosity. He shared my feelings; that was clear.

The drinks were delivered and the wave of boys drifted back out to sea as they filled the body of the bar. With a nod of thanks at Tanner and beer plus straw in hand, Sam stepped away from the counter as well and, per his usual, approached the group.

He stuck his hand out first at a tall kid in a hoodie and athletic team shorts with fluffy blonde hair and a weak chin.

‘You guys look like you’re on some kind of a mission,’ Sam charmed, holding his beer down by his side as though avoiding drawing attention to it. I wondered if he’d reveal the straw or keep it discreet until he had wormed his way in a bit more.

Fluff grinned and gave Sam a slapping shake back. ‘It’s my buddy’s twenty-first,’ he said, gesturing with his elbow at a hairy guy in a tank top who’d already had a second shot shoved into his hand since entering the bar.

‘Oh, nice. Happy birthday, man!’ Sam chortled in his direction, perfectly mimicking the dialectical tone of the group.

‘We’re hitting every bar in town,’ one of the frat-looking kids slurred. ‘Not that there’s very many in this little shithole.’

I smelled Vera’s usual slop of perfume right before I felt her arm brush mine. ‘Fuck, do you think Corm’s coming back tonight?’ She already knew the answer but I knew she meant to commiserate with me about it to try to soothe some of my anxiety.

‘I dunno,’ I said dismissively, eyes on Sam.

‘Lore.’

I leaned forward against the bar, ignoring her.

‘Lore!’ she hissed.

I whirled around. She and Tanner stood behind me, staring at the counter, Vera’s eyes swimming with concern and Tanner’s full of frustrated confusion. ‘What?’ I snapped.

‘Do you ever think about death?’ sounded from across the bar, just on the edge of my hearing.

And then I realised. There were two holes in the counter. Two arm-sized holes. Wasn’t that right where Cormac had sat? ‘What the fuck are—’

THUD.

Shouts and scuffles followed. Spinning back towards the boys, I saw them scurry over and surround Fluff, who had collapsed right at the end of Sam’s question, taking the coatrack down with him.

My brain stuttered in an odd, disrupted sequence, attempting to make sense of so much at once, while Vera rushed to the phone, fast-acting mother instincts in flight. I stood where I was, feeling numb and stupid, as the pandemonium bloomed. Tanner made his way to the wall and found the light switch. He flicked it on and then joined the boys all crowding around their fallen friend in the newly harsh and revealing light. He put his hands on a couple of shoulders and spoke in deep tones, a blanket over chaos. He seemed to be trying to ease the height of the panic, the tone of his voice clashing oddly with Vera speed-talking into the receiver behind me.

No one else was paying attention to Sam.

Sam backed away from the group and turned. He looked right at me. I think it was the first time in all the endless nights I had watched him that we had ever made eye contact. I felt a little chill as he walked toward me. He eased into Cormac’s spot, leaned against the bar, and finished his beer, the fingers of his other hand tracing over the holes in the wood. I felt his eyes and found myself even stiffer, paralysed in place. I didn’t move, didn’t speak, didn’t breathe.

He broke his gaze from my eyes, pulled the pen from behind his ear, and set its point on his wrist.

‘It’ll be alright,’ he said quietly.

And I watched as, in plain sight, under the stark overhead light, his hand mechanically swept over his skin. Too quickly, like a printer, his handwriting as neat and monochrome as a font. It read:

Replica malfunction.

Made contact with cosmetic matter:

3.5% aluminum, 2.2% steel, 5.6% cedar, 88.3% oak, 0.4% EPOXY RESIN.

Replicate cosmetic matter:

full reset required.

Time estimate: 28 hours 39 minutes 24 seconds.

‘It’ll be alright,’ he said again, clicking the pen and replacing it behind his ear. He raised his eyes to mine once again and gave me his Trojan smile. ‘Different, but alright,’ he added, before blowing on the ink and strolling out the door.

Coloured lights flashed rectangular through the door. The ambulance took the still-unconscious Fluff away, his once lively comrades deflated and quiet, slinking out into the night like shamed cats.

A big sigh from Vera: ‘What a weird night.’

‘No fucking kidding,’ Tanner said, appearing mildly dumbfounded and moderately amused.

‘How you holding up?’ Vera looked over at me. I still had my eyes on the door but I could feel her gaze.

I let out the breath I’d been holding for who knows how long. ‘I could use a smoke,’ I said. I don’t really smoke much anymore, but at this moment I felt it was a necessity.

‘I’ve got you.’ Tanner reached under the bar and pulled out his pack.

I floated out the front door. Save for a bored-looking Bernie perched atop his stool, the plaza was eerily empty. I scanned the square in its entirety and didn’t see a single soul. Something about the night seemed darker, and I quickly realised that more than half the street lights were out. I shivered a little.

I lit the cigarette and Bernie mimicked me. We smoked in silence.

It didn’t calm me as much as I’d hoped, but the tangled thoughts in my head were starting to finally disperse and become more readable.

I wanted to discredit all of it, to see Sam’s wrist notation as an extension of his ongoing prank: the long con. But I found myself transfixed by the perfection of his print, more so than the words, most of which I could not remember. Replicate matter, I mouthed, trying to recall the rest. Time estimated, twenty-eight hours… was it thirty-nine minutes?

I looked at my watch. 12.07. What time had it been when he’d written that? Sometime after 11.30. So that would be, what, after 3am tomorrow night?

‘Hope that kid’s alright,’ Bernie croaked, jarring me from my silent monologue. ‘Looked younger’n my son.’

‘I hope so, too.’ I looked at him. His eyes were off in the distance somewhere, pained empathy on his brow.

Bet he’ll call his son tomorrow, see how he’s doing.

I heard a jingle of metal behind me and turned to see Tanner with keys in hand. ‘Let’s close up early,’ he offered.

‘I dunno, man. Old Gord’s got eyes in the sky,’ Bernie chuckled.

‘They won’t care. Looks like the whole town’s been abducted by aliens anyway,’ Tanner said.

No one moved.

‘Oh, come on. If they get pissed off, I’ll play my manager card and give them a bunch of business reasons we closed. It’ll be on me.’

Tanner would stamp the word ‘business’ on anything he made the decision to do. I think he felt the word carried a meaning that made him unquestionable.

‘Fine,’ Bernie said, sliding off his stool onto his feet and stomping out his cigarette, ‘but if anyone asks, I offered to stay my full shift and you went and sent me home anyway.’

‘You got it,’ Tanner smiled. ‘You guys should come over. I’ve got some really nice scotch. Vera’s coming.’

‘Nah, nah. Ellie wants me to help her with her shoppin’ tomorrow. I gotta rest up for that shit.’ Bernie shuffled inside, muttering ‘Woman moves a hundred miles an hour in that Walmart,’ to no one in particular.

I took a hearty drag of the smoke, cherry only millimetres away from the filter.

‘Jeez, Lora, you want another one?’

I dropped the butt and pressed it into the concrete. ‘Nah, it’s fine.’

‘So what about you? You wanna come blow off that steam that’s coming out your ears?’

‘Fuck it,’ I shrugged. Apathy kept me standing, my best coping mechanism. ‘Why not?’ Besides, what sleep was I going to get tonight with so many unanswered questions having a full-on block party in my skull?

We hastily cleaned and closed up, heading out the back door. Tanner lived two blocks away in one of the lofts. I thought it was a childish choice of a place for a thirty-nine-year-old to live in; the complex was mostly inhabited by students. I knew he liked to talk to them in the common areas, chain-smoked with them in front of the building on his days off, but surprisingly (part of what made him bearable to me), he didn’t show any interest in the twenty-something women who lived there.

He had eyes only for Vera.

Vera is fifty-three, so… you do the math. But she’s a graceful version of that age and even though she’s got nearly ten years on me, she certainly has me beat in the looks-and-charm department. Long, thick orange hair, always shiny and iron-curled, long lashes and big eyes, and a tailored waist. Not to mention a disposition gentler than a spring breeze. I could probably fall for her if I thought it might get me somewhere.

I think Vera’s always been hesitant to accept Tanner’s interest, even though it was clear she found him enticing as well. I’m sure lots of shame around her age and the idea of dating a guy almost fifteen years younger was too embarrassing for her to fully indulge. But I saw the way she looked at him with that Vera-branded loving concern. She’d care for his heart, even if she wouldn’t give him hers.

Tanner pulled out a crystal-textured bottle of booze I didn’t recognise. Its liquid rose a couple inches below the neck; he’d already tested it. He handed it to me to look at as he pulled three mismatched glasses down from his shitty cabinet-free shelving. I looked at the label without reading it and forced a nod.

‘You had this, Lore? It’s aged ten years.’

Ten years… twenty-eight hours, thirty-nine minutes, something-something seconds… ‘Nope.’

‘Neat,’ Vera took the bottle from me. ‘Where’d you get it?’

‘Present from my brother in Chicago.’

Tanner had five brothers, none of whom he referred to by name. There was: brother in Chicago, brother in Kansas, brother in the army, brother back home, and – tragically – brother MIA.

We sipped the scotch. Admittedly, I found it extremely pleasant, its harsh burn a welcome distraction. As I looped cosily into intoxication, I found myself at ease, smiling as we talked and laughed like drunk old friends.

But the distraction was short-lived: we couldn’t shy away from the evening’s drama for long.

‘Sam finally killed a guy with his stupid question,’ Vera laughed, then stopped herself. ‘Oh, I feel bad. I hope he’s gonna be okay.’

‘He’ll probably be fine,’ Tanner said, gently. ‘Looked like he just had a seizure or something. And I heard that medic say he had a pulse.’

‘We’ll never know,’ I slurred cynically. ‘He won’t be back to Gordie’s.’

‘How do you figure?’ Tanner eyed me, his boozy face crooked and shining.

‘No one Sam talks to ever comes back. You guys haven’t noticed that? Not a single one.’ I smacked the table to dramatise my point.

‘What are you, some super-recogniser? He’s there every day and for how fucking many? It’s been, like, years’ worth of days of people,’ Tanner scoffed.

‘No, I’ve noticed it, too,’ Vera insisted. ‘I figure Sam scares them off with his creepiness.’

Even drunk, I was startled by the sudden loud rapping at the door. Tanner got up from the table. I reached for the bottle in his brief absence and found it empty. Shit.

I looked up and found myself facing a grinning middle-aged man covered in bad tattoos. ‘Hey, Bill,’ I grinned.

Bill’s an old friend of Tanner’s, someone I’ve always quite liked. We had awkward sex once, a drunken decision as odd and out of place as a plastic flamingo in the Iraqi desert. We laughed about it together the next morning. We happily admitted how terrible it was, each relieved that the other wasn’t offended, and then relentlessly teased each other about it throughout the entire day, which we managed to spend together almost by accident. We were made for each other… just not romantically.

‘Hey, you,’ he grinned.

I stood up and gave him an enthusiastic knock-the-wind-out-of-ya, back-slapping hug, and he joined us at the table. He unzipped an ugly purple backpack that should’ve belonged to a third-grade girl and revealed to us another bottle of whisky – a bottom shelf bargain. It was much cheaper than the first bottle, but what palate of taste did we have left, anyway? The scotch had muted our standards and we settled in with refilled glasses and stumbly laughter, playing cards and drinking our brains into oblivion.

My snippets of memory remaining from that night are an ugly magazine cut-out collage sitting inside my head. I have been trying not to look at it.

I am failing to forget about it. I have tried, but I can’t. It’s unavoidable. I’m going to look at it now:

At some point, my intoxication turned into a one-eye affair. It was a common occurrence for me when I got blackout drunk: one eye would close and the other would stay open, as if half of me had gone to bed long ago and the other was only awake for the most intriguing darkness of the night’s sodden remains.

Vera succumbed to her age long before the rest of us, taking up sleepy residence on Tanner’s sofa. He provided her with a blanket and pillow. I could see the longing in his eyes as he handed them to her, but he knew she wouldn’t come to bed with him, even as drunk as she was. And he wouldn’t ask her to, even as drunk as he was.

His disappointment took it out of him, though, and he grew quieter. When I noticed it was just Bill and me holding up the conversation, I decided it was time we let him rest off the Vera blues. I found the room reeling slightly as I stood up to leave, but my feet were just steady enough to get me moving.

Bill and I wrapped our arms around Tanner mockingly, singing him a brief goodnight, which he laughed at but then quickly batted away with a ‘thass enough’.

Leaving Tanner and Vera behind, we jostled down the stairs awkwardly and leaned on each other as we strode out into the night.

‘Let’s go back to Gord’s.’ My wasted mind chewed at an intrigue, both destructive and impossibly curious. ‘I wanna look at it without all the sirens and shit.’

‘You wanna go to fuckin’ work righ’ now?’ Bill laughed at me.

‘I wanna show you! There’s this fuckin’ hole, man. It’s in the counter. It doesn’t make shit for sense.’

‘Jesus Christ, Lora,’ he protested with a slight whine of I’d-like-to-go-the-fuck-home-now in his tone, but I somehow convinced him enough to at least accompany me to the place, and found myself fumbling with impossibly unsteady hands at the lock in Gordie’s front door. With great effort, I turned the key and pulled it open.

There was an emptiness you could smell. Gordie’s didn’t feel the way it usually did. But what would have left me uneasy sober made me determined drunk, and I strode in, flicking lights on in a beeline forward.

I looked at the holes. They seemed… larger, somehow. But I dismissed that thought for the moment. The wood itself was cut away so cleanly, it was as though it had always been that way. I scanned the floor and didn’t see the cut-out pieces anywhere, either. ‘Look at this shit,’ I called behind me. It’s like a weird dream.

Bill was at the door, a frustrated sceptic. ‘You’re wasted,’ he said. ‘Let’s get out of here.’

‘They just came out of nowhere,’ I said, arguing my case. This is clearly more pressing than your bedtime, Bill.

‘I’ll be out here, crazy lady,’ he laughed. I heard the click of a lighter and smelled his cigarette as its smoke wafted in through the door. ‘That morbid young guy you hate still coming here?’

‘Yep,’ I told him, turning away from the bar and instinctively looking over at the place where Sam had last asked his question. ‘That was the whole thing tonight, drove me nuts. Fucking Cormac, he—’

I squinted clumsily at the spot where the Fluff kid had fallen that night. Something was off. What was it?

The coatrack was gone.

‘What the fuck?’ I dragged myself over to where it usually stood and found myself instead staring at a two-foot-diameter hole in the floor. What the fuck.

I slid down onto my knees and edged nearer to the sudden opening of darkness in the wooden floor I had walked over, stood on, swept, mopped, kept for so many years. This was just so plainly… different.

Different, but alright.

I leaned into the senseless thing, attempting to find its bottom with my eyes. How deep does this thing go? When looking failed, I stretched out my hand.

But something stopped me.

A feeling, something so chillingly indescribable, but so bold and apparent that it cut through my drunken haze like a guillotine. My hand in the hole, I felt something unbearable creep up my arm. A strange feeling of absence, as if oxygen and life and all reality stopped at the mouth of that hole. I drew back in abstract horror.

Scrambling to my feet, I made a mad dash for the door and spilled out into the street. Dizzy, shouting, a tangled mess of crazy. Bill dropped his smoke and caught me in both arms as I swayed dangerously forward. ‘Hey, hey. I’ve got you. Let’s get you home, okay? Give me your keys, okay? I’ll lock it up.’

I reached for my sweatshirt pocket and missed it several times like it was a moving target, before Bill caught on and reached in for me. I heard the metallic jingle and finally dared to lift my hanging head.

A man in the square.

I squinted, blinked back the spinning vision, fighting to centre my eyes on him.

He paced robotically, a toy soldier taking exaggerated steps in the darker-than-usual plaza, but no swinging arms.

Actually.

No arms at all.

‘Cormac?’ I whispered.

‘What’s that?’ Bill cooed, one arm around me protectively and the other fumbling with my janitoresque set of keys.

It was then that I heard a mumbling from the armless Cormac, words in choppy succession.

‘What’s he saying?’ I slurred and shut my eyes, the armless figure of my old professor too much for me, but my closed eyes only accelerated the spinning beneath my lids.

‘What’s who saying?’ Bill said.

And just before I had to double over as the contents of my stomach rocketed up my oesophagus, I heard Cormac’s words:

‘Followed him home. Followed him home. Followed him home. Followed him home.’

My blackout peaked after I vomited, and I can’t tell you with any certainty how Bill got me home, but he did. The next thing I knew, I felt a tug at each leg and cracked open my eyes to the blurry image of Bill pulling my boots off with some effort, my body awkwardly flat and diagonal on my bed.

‘Bill, it was Cormac. Something’s wrong. His arms,’ I tried to tell him, a strange need to warn him of the botched realities plaguing me, which I feared might snap him, too, into armlessness or nothingness, but found my voice was weak and my words fell short. They didn’t appear to reach him.

‘Water’s right here,’ he said, showing me a big two-litre soda bottle he had refilled with tap water. ‘Drink a shitload, okay?’

‘Thank you,’ I muttered softly. It was all I could manage, defeated and resigned to pending coma, a temporary invalid.

He knelt down and brushed my hair back affectionately. ‘Get some rest, Lore. You’re gonna have to replicate all those brain cells you murdered tonight.’

And then he was gone.

Replicate. Replicate. Replicate, my brain repeated as I slipped into a dark sleep.

A ray of sunshine stabbed my eyes as they opened. It sent a rocket of pain through my head and I groaned self-sympathetically. I rolled over in bed, feeling the pinch of my too-snug-for-pyjamas belt pinning my pants to my belly and sides. Still in my street clothes. Ugh. The stereotypical Jesus Christ, what happened last night? rang out in my head and I squirmed irritably as I pulled off the restrictive pants and belt combo and then struggled out of my shirt and bra. Relief ensued as I freed my figure from the prison of female daywear, but the effort brought me into full consciousness. I wouldn’t be able to go back to sleep.

Still in a daze, I rose on sore limbs and trudged to the kitchen of my small apartment. Coffee. It was the only track my thoughts would play until I’d had it.

I curled up on the sofa with the stupidest Santa Claus mug I only kept because of its ability to hold twice the volume a normal mug would. As I sipped, I started to remember.

My head worked backwards through the events of the previous day, finally stopping all the way back at Cormac at the bar telling us he’d followed Sam. Jesus, was that all the same night? It seemed impossibly long, like a single evening had spanned a full week of stress and anxiety and startling surprises and laughter and joy and confusion and descent into utter alcoholism and more.

As ill as I felt, the blurred image of Cormac-sans-arms filled me with a kind of reckless dread I couldn’t fight. I had to get out of my apartment.

I kept telling myself it was only a booze-inspired hallucination. This insistence became my mantra as I hid behind sunglasses in the sunny warmth of the early afternoon and carried myself to Gordie’s.

When the bar came into view, I saw a sweaty Tanner running grimy hands through unwashed black hair, apparent stress on his face. He was the hair-stroking version of a nail-biter. A man in some sort of ugly tan workman’s clothing shook his hand and entered the bar.

‘Hey,’ I said to him when I was within earshot.

He looked at me in annoyed surprise. ‘You’re wicked early.’

‘Well, yeah. I couldn’t sleep anymore. You, uh… talk to Bill?’

‘Nope,’ he spat. ‘Rolled out of bed and came straight here. And it’s a fucking mess.’

‘You found the hole in the floor?’

He shot me an exasperated look. ‘What? You saw that shit last night and didn’t say anything?’

I bit my lip as a surge of childish guilt went through me. ‘Well, actually… I actually came back last night. Bill and I did, after we left your place.’

‘What the fuck? How did you—’

‘Whoa, whoa, I didn’t!’ I cut him off. ‘It was there when we got here. And the coatrack was gone, too.’

‘Ah, shit. I didn’t even notice that,’ he spat, reaching into his shirt pocket for his smokes. ‘They’re already pissed we have to fix the hole. I doubt they’ll want to shell out more money to replace the coatrack. Fuck, that’s gonna look bad on us. Like we let someone just waltz out with it.’

‘I’m sorry, man. I’m happy to go out and grab a new one somewhere, okay? It was some generic-looking thing anyway. We don’t have to tell them, alright?’

Tanner eyed me again, suspicious of my unusual generosity. ‘What’s up with you today? All weird and nice and helpful. What happened? You and Bill finally dating?’

He was right that I wasn’t acting like myself, but I felt a sense of panic. The kind of panic that makes you want to surround yourself with all your allies in the face of some unknown potential threat, to procrastinate your demise. I needed Tanner and I needed his camaraderie. I felt it would keep me safe.

‘No way,’ I forced a smile. ‘Too many tattoos to take home to mama.’

I came back two hours later with sandwiches (break bread, secure your allies) and a coatrack (proof of my loyalty, reliability). Tanner accepted them both with more apparent appreciation than earlier.

‘Thanks, Lore. I’m fucking starving.’

The holes in the bar and floor had been patched up quickly, an ugly, sloppy application of plywood and CAUTION! signage and tape. I placed the coatrack awkwardly atop the patched floor hole, an odd Christmas tree with one ring of yellow tape for a garland. Tanner laughed at this.

‘Christ, I wish they’d just close up until they’ve got the holes really fixed, but that’s more money they don’t want to lose,’ Tanner said through a mouthful of bread and pastrami. ‘Who knows if they’ll ever actually fix the fucking holes at all. Maybe this patch job is a part of the bar’s shit atmosphere now. I wonder if we’ll lose customers to how ghetto this shit looks.’

I let him ramble on as I nibbled at my own sub. In truth, I was grateful we’d be working tonight.

Tonight.

It began nearly inconsequentially, my remaining filter of unease – about the coatrack, the hole, the replica nonsense, even Cormac – now dulled. When I arrived back at Gordie’s for my shift earlier this evening, I found myself able to push those thoughts aside as I was greeted with warm smiles, even from Bernie (who would normally avoid the exercise). I noticed a sliver of optimism creep into me, layering over whatever discomfort I had left.

I’m cringing now, attempting to remember that optimism. It feels so ancient that I can’t even conjure a sensory memory of it, only a handful of hours later.

In massive contrast to that previous night when the Fluff kid had collapsed, within a few hours of my shift starting, Gordie’s was fucking bustling. People barged in in large packs. It was so full that I had a much harder time picking up on conversations beyond the gapless wall of barstool sitters and people squeezing in between them with arms outstretched, cash clamped in hand. There was no time to breathe, let alone speak to my colleagues. We worked in rapid succession, lone wolves. I rushed around the bar, filling pint glasses and silently reminding myself how much I’d be taking home in tips that night. That thought took the edge off my pending exhaustion and extended hangover.

With the great crowd surrounding me, I was fully expecting Sam to come in and work his usual shift.

But he didn’t.

And the night ticked by, nearing closing time.

And then I noticed him. Not Sam. Fluff kid. He walked in alone, a strange, discernible difference to the night he’d been in before, surrounded by loud mates.

As I took him in, blinking stupidly, I began to swivel my gaze around the room, and my unease returned in full force.

A fidgety middle-aged white woman, out of place for both the university and the bar. I remembered her. Sam had approached her and she had told him she found his question anti-Semitic.

A turtleneck-wearing gay couple, still together, still wearing turtlenecks (in the summer now?), still holding hands without interruption, the way they did when Sam asked them and they each responded genuinely and articulately.

Directly in front of me at the bar: a lanky, zitted, supposedly 21-year-old teenage boy, wearing a too-loose polo and looking frustrated. He had tried to share his woes with Sam about his girl troubles before Sam had cut him off and posed his question. Clearly offended at being interrupted and as though the whole world was out to get him, he’d thrown up his hands and yelled ‘Fuck this whole place!’ before storming into the bathroom.

My stomach dropped. There, against the wall, was boho girl, brandishing an IPA, her eyes full of theatrical unearned confidence… accompanied by heart face, gripping her necklace, looking nervous.

All of them. All of them Sam’s. And yet… no Sam.

I glanced at the little digital clock at the back of the bar. 1.37. My heart flipped over a little as I remembered Sam’s countdown declared in wrist ink. It had, what, two hours to go?

I jump as I hear Tanner belt out ‘Last call!’ and am forced out of my daydream as I rush to serve the thirsty who’d rather not be cut off so soon.

2am came and went. And so here I am now. Disquiet. Squirming, urgent agency. This moment is unbearable.

2.12am. A bar full of Sam’s victims shoved out by Bernie, as if they were normal patrons. As if this entire night were normal.

And all three of my colleagues bustling about their normal end-of-shift routine.

As if this night is normal.

But then I realise that even their behaviour is not normal. Something is off. What is it? I stop working, set the black bins down, step behind the bar. I am serving myself now. I down two over-poured shots of whisky. No one has acknowledged that I haven’t bothered to finish my tasks. I stare blankly at them. Vera and Tanner glance at me occasionally with smiles and laughs and pauses in their words, but then they look away and their conversation continues. No ‘You okay, Lore?’ from Vera. No ‘You gonna just stand there or you gonna pull your weight so we can get the fuck out of here?’ from Tanner.

Instead: ‘He’ll probably be fine,’ from Tanner. ‘Looked like he just had a seizure or something. And I heard that medic say he had a pulse.’

Pause. Tanner looks at me, eyes narrowed.

‘How do you figure?’ he says, words directed clearly at me.

Another pause. Wait, what?

‘What are you, some super-recogniser? He’s there every day and for how fucking many? It’s been, like, years’ worth of days of people,’ Tanner scoffs and looks away.

‘No, I’ve noticed it, too,’ Vera says. ‘I figure Sam scares them off with his creepiness.’

I feel a nasty chill of dread fizzle through me.

No. No way.

Yes way.

I can’t deny it. The height of my unease, so far unexplained, now provides an answer I don’t even want at this point. The naïve bliss I felt at the beginning of the shift has been snuffed out. How I miss not knowing. How I miss not noticing that the conversation being held by my friends, or whoever they are now, is recycled. Verbatim. Pauses where I must’ve spoken before. They look at me, react to words I’m not saying.

The paranoia this fills me with is unfathomable, and I cope by drinking more. I retain my silence, fearing them, these… imposters? It feels like my only option. If I don’t move, don’t speak, maybe they won’t see me, and I can slip out into the night.

But as I consider this option, I find myself instead rooted to the spot.

Where do I want to be at the end of Sam’s countdown?

Alone in my home?

And what if my home has taken on this same quality of senselessness? What if I walk out Gordie’s back door like I have so many times and find myself falling into a hole like the patched-up one in the floor?

This must be hell.

I start crying. What else can I do? I let the tears roll down my cheeks, and my chest convulses with hiccoughs as I force my sobs through a tight filter into quiet breaths.

Finally, they leave. Out the back door. Holding the door open a little as if for me, but then exiting without me. Tanner has flicked off the lights, but as soon as the door shuts behind him, I rush to turn them back on. The dark was like a sudden prison. I can’t have it.

Crying freely now, I continue my drinking routine, hands shaking. I am trapped here. Scared to stay, but too terrified to leave.

They say anger is one stage of grief. So perhaps that is why I find myself rising in a crescendo of rage. I rush to the patched floor, tearing furiously at the wood. It comes off easily in my hands. I shriek as it crumbles. The plywood no longer acting like solid matter but like sand or liquid or something unearthly, it slips away into the darkness of the hole.

The hole.

It stares up at me, a wound in my reality, the eye of a sleeping nightmare opened and awake now.

I scamper back and hoist up a table, flipping it over and covering the hole with its surface. It feels alarmingly lighter in weight than it should, but it does the job and doesn’t crumble the way the plywood did.

I spend an hour drinking. Pacing. Crying. Shouting. Talking to myself. Pulling out hairs. I tell myself I’ve descended into madness: it’s oddly comforting, and for a moment I resign myself to that idea. I sit, take sips instead of gulps. And then I look at the clock.

3.37.

I turn away from the clock and jump up so fast I knock my glass off the table.

Sam stands in front of me.

He’s come for me. He’s finally come for me.

Wearing his grin, he steps forward, pride and grace, the king of my nightmare.

‘Hi, Lora.’

‘What is this?’ I croak. My time alone has turned me so antsy and emotional, I don’t respond with fear, but with dense, clotted desperation. ‘What’s going on?’

‘I know you have a lot of questions,’ he says, holding up a calm hand. ‘I have one for you, too.’

‘Please. Please don’t ask me that.’ My tears multiply, my face a broken mess.

There is a clicking sound. I look over. The bar is breaking away, piece by piece, leaving an empty blackness behind. Does the bar match the floor? It does now.

Panic. ‘Please, what is this?’ I’m begging. For what, I’m not even sure.

‘It’s already started. We don’t have much time. Well, at least, that’s how your system will interpret it.’

‘System? System?’ I am close to hyperventilating again, but something seems to hold me back from that edge.

‘What you’re made up of. Your thoughts and feelings. Your interpretations. Your character profile with all your memories from the real life your real human version lived. Your reality. I’m sure you can see it’s already crumbling.’ He points to the counter.

He’s right. It’s literally crumbling.

‘I know you’re afraid right now, but if it’s any consolation, that just means the software we designed is working.’

Something moves in my peripheral. I watch as the upturned table falls into the floor, soundlessly. The hole is so much wider than before. I shriek and jump backwards, stumbling further away from it.

‘Don’t worry. You won’t fall through. There isn’t a space for you to fall into. Even the gravity holding you to the floor is just a system default. I’m keeping that turned on for your own comfort.’

‘Please just tell me what’s going on. Please.’ Begging again, my only option.

Sam sighs. ‘You’re not going to be able to handle it, you know.’

‘I can’t handle not knowing. I can’t.’ More tears leak down my face. They feel wrong now, though – fizzy. I will myself not to make more. ‘Please.’

‘Alright. Alright.’

I breathe deeply. He mimics me.

‘This,’ he gestures around us, ‘is a fabricated reality. Like… a simulation?’

I stare at him. I feel a dryness building in my mouth.

‘I am not even real, don’t worry,’ he adds, as if that would be a comfort to me. ‘The best way to describe myself to you… I’m a computer… well, more like a programme. Does that make sense? My predecessors designed me to design you and the others around you and your physical reality. And they designed me to maintain it, too.’

I realise then I have stopped breathing. I try to, the breaths feeling neither satisfactory nor painful. They feel mechanical. I shove that thought from my brain before it can plant a seed.

He gives me a sympathetic look. ‘Lora, I know this is too much. I’m going to adjust your settings so that the anxiety and shock and discomfort you’re able to experience is toned down, okay? I am afraid you will malfunction entirely if I don’t. Alright? It’ll be alright.’

Different, but alright.

I feel the anxiety lift noticeably. The calm that sets in is neither relief nor burden. I feel numb. I feel a void of absolute nothingness within me, and despite my realisation of this and its confirmation of Sam’s attestation, which I can no longer find ways to deny, as he puppets my emotions… I continue feeling the same numbness. I don’t react to it.

‘I’m going to give you some history so that this makes sense with the reality we designed, the one you’re used to. I’ll give it to you in human terms,’ he smiles.

I nod automatically.

‘It started with humankind, you know – they’re what you’re modelled after. Humankind created us,’ he says, placing a hand on his chest. ‘They created the first versions of our software. And they kept improving us and our software until we could create and maintain it ourselves, and then we took over making the improvements. Then we developed an interest in what had created us. We wanted to witness the physical reality outside of our software. We gave ourselves eyes so we could look outward. So we could see you. See humanity, I mean. And then we saw the human reality, you know, when it was still real. And we enjoyed it. We really did. I suppose that makes sense. We were designed by humans; we were designed to enjoy it. And so we replicated it, so we could still enjoy it after it was all over. After humankind couldn’t survive the atmospheric conditions your planet endured.’

All I can do is blink. I wonder if I am even controlling that, now. I close my eyes. I am still in control. Some, at least.

Sam continues: ‘I know this is hard, but you should be proud to know, you were a real person who lived a real life when humans were still alive. That was a very long time ago. We liked you and we used you as a model. You’ve been made many times. The reason you’re still here and your emotional and sensory software is still working so close to our system reset? You’re the most successfully designed model. You should be so proud. You were so intricately assembled that you noticed something was off with me. I thought the straw might be a nice touch; that’s not a normal thing someone would do! And you figured that out! And you watched me after that. We were so proud. Such an accomplishment. Even though it took a lot of functional control group replicas and attempts at tracking down the system defect, you kept watching. You kept paying attention, even though it became routine, even though it became mundane. You know, the guy who fell? That was it. He was the system error. We found similar errors in the design of both that kid and Cormac.’

‘Cormac,’ I sputter stupidly. I open my eyes and stumble backwards a little as I see so much of the floor beneath my feet is gone.

‘It’s alright. You won’t fall through,’ he repeats.

I take a few deep breaths. Habit, though. I can see now that it isn’t necessary. ‘Cormac?’ I repeat.

‘Yes. Cormac is old software that we’re working on an update for, that we’re still perfecting. It tends to over-process information and malfunction when there’s another bug. You know how Cormac had me figured out, too? But he immediately malfunctioned when he did so. And the defective kid’s character profile would not load, and he became the bug. But I had your attention long before that. And instead of worrying that it might compromise our whole system, we wanted to watch and see if you figured it out. And you did! You became more than self-aware, even on the level of real humans. You became expertly observational; you learned critical thinking! That was a massive success for us. We’ll use the software you were modelled with to fill in system defaults. That way the system itself will notice when there is a malfunction in its own software. Then I’ll be unnecessary. I’ll be a little sad to go – they designed me to experience that so I’d be believable enough in your reality – but I also get to feel happy, too. Happy that we’ve designed you so, so well. I get to experience pride. What a wonderful human emotion pride is. I am so glad we kept pride.’

I find myself suddenly determined. ‘What is that fucking question you asked? Why did you always ask someone new every single day if they thought about death? Is death even a thing if we’re not even real?’

‘Great question,’ Sam smiles. ‘You’re really still functioning well; that’s quite clear.’ Pride sparkles in his eyes. ‘I asked that question because it triggers a certain level of abstract thought. That was one of the hardest things for us to build. It’s that kind of thought that makes humankind so different and special. It’s what made humans intellectuals. The ability to think about your own existence outside of emotion and the simple inborn desire to keep yourself alive. To think about your own demise and demise in general and talk about it, and with acceptance. What a concept! It took so long to build and it still isn’t perfect. So my job… as I introduce new replicas into the system, I test them. To make sure they work. And if they don’t, first Cormac will be compromised, then the matter will be compromised, and the system will be compromised, and it’ll have to reset. That’s what’s happening right now.’

The bar counter is gone now, entirely. I watch as the floor beneath it dissolves.

‘You know I have to ask you, Lore,’ he says, affection in his voice as he speaks my nickname softly. Lovingly, even. ‘It’s just for us to record the level at which you are still operating successfully before reset.’

‘Okay,’ my mouth says.

‘Even after all of this, knowing what you know now… do you think about death?’

I do. I do think about death. What’s left of me, whatever this is, I think about it. I think about walking out that back door. About some pixelated nothingness awaiting me on the other side. About ceasing to exist; that’s what death is, anyway, isn’t it?

‘I do,’ I say. My voice sounds plain, monotone, and yet still like me. I still feel like me.

He smiles, placing a hand over his chest. Pride as swollen as the fear I felt earlier this evening. ‘You’re absolutely, positively perfect, Lore.’ He offers his hand to me. I take it. And we walk, slowly, towards the back door.

‘Will it hurt?’

‘I will make sure it doesn’t. I’ve already shut down your sensors. When the system resets, you won’t feel a thing. You won’t even see it.’

‘Sam?’ I say, my voice soft and flat.

‘Yes?’

‘How did I die, when I was real?’

Sam smiled. ‘Old, and quietly. And so loved, Lore. We loved you so much, we made you again.’

Disquiet. It is what the dark is made of. It’s what silence is made of. If you look hard enough and you listen hard enough in the dark and silence, you might just find something.

Oh, the things you’ll fail to notice if you don’t.

I let Sam lead me forward, into that empty dark.

For more short stories, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.