The Gold Rimmed Glasses

I remember how I was coming out of university: lofty, strong ideals, but incredibly lazy. I read a lot, got into long-winded discussions with no definite conclusion and generally loafed about. At university you could do all this with impunity but now that I’d left it was frowned upon, and being known as the person who rested on their oars the whole time was a detestable image. I was lucky, you see. Money wasn’t an issue and I had the luxury to figure out what to do with myself. The proper way of doing that is to get out in the world and try lots of things but being inexperienced and indolent, I preferred to lie on the sofa and think my way through it. Funny now how I can’t remember any of the thoughts I had at that time. Nothing very profound came my way and I made no solid conclusions as to what to do with myself.

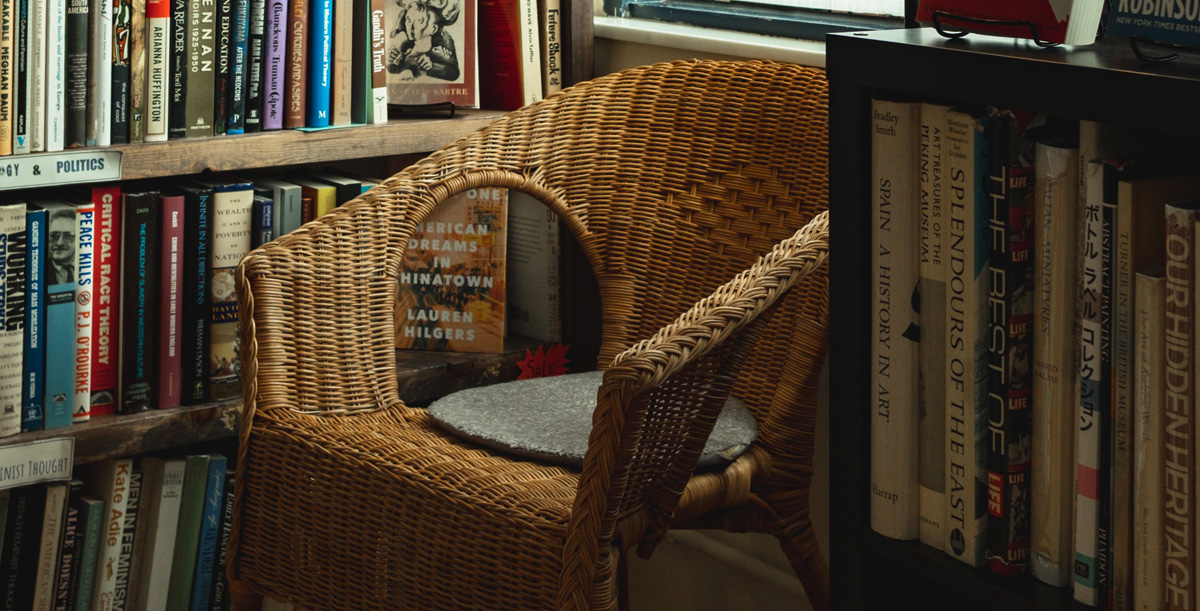

Motivation is sort of a mystery. No one knows what sparks us to actually get up and take the first step, but suddenly I became sick of having nothing to do so I started helping out at the second-hand bookshop. I used to love walking there. It’s right on the green and I loved passing all the cafes on the way there, trying to construct little stories about all the people sitting there, sipping coffee and chatting to their friends. The shop had a great selection and the workers always treated me well. I was happy to spend hours up in that dusty storeroom or standing by the downstairs till. Although it did get tedious, constantly telling customers that it was out of order and that they’d have to pay upstairs. There’s only so many times you can say that before the words become cold and you begin to say them with a kind of resentment.

But in spite of it all, I liked working in the bookshop. It was honest work. I hear people working in those grand offices mention all the little white lies they have to tell. If you question them, they’ll shrug their shoulders and tell you it’s just the sort of thing you have to do. I’m not a religious person but I’ll be the first to say that lying corrupts your soul. Your job takes up eight hours of everyday so if you have to lie in that time – how can you be anything but a liar? I never had to lie in the shop. There was no game to be played and I could see right in front of me exactly where the fruits of my labour fell, in the same way someone building a house never has to doubt what the actual purpose of their job is.

There were always people to talk to at the shop. Carol, an old, short-haired woman and ex-literary agent, had all sorts of stories about famous authors she used to represent.

‘So-and-so was an angel. So-and-so was a nasty man.’

She belonged to a particular set of older women volunteering at the shop who, having lived in the area since the eighties, were now sitting on two-million-pound houses and wanted nothing more to do than be around books all day.

There was Finn, a pasty, elderly gentleman who would visit every week and always ask if it was okay to leave his bag behind the counter. Every week the answer was the same: ‘Of course, Finn, you don’t have to ask.’ But next week, sure enough, he would ask it anew. He began talking to me one day, somewhat out of the blue, about Indian philosophy and how reincarnation was the only way to account for the perpetual suffering in the world. He was a devout follower of Gandhi and believed that the only way for us to stop conflict and war was to adopt a stance of non-resistance.

‘Inaction can save the world,’ he once said. I’m really not sure I believe him.

There was also Jess, who was sort of my boss although she wasn’t paid. She was a couple of years younger than me and a great deal shorter; a detail I never let her forget. She had thin eyes, a bright head of hair and this hunched look, as if she was burrowing everywhere, like a beaver. She could read a book in maybe three hours, was politically minded but, to my surprise, always said she hated the theatre.

‘I don’t want to be told what the characters look like. I want to imagine them for myself.’

I’m only writing all this to give a complete picture of my life at that time. I feel I could go on for hours describing every customer who came in and feel like I wasn’t wasting a word. I want you to be able to see what I did. I wish I could describe how it felt to be in that dusty room, looking over the ragged roofs off towards the city, to see that old man’s face every week, to hear those stories or to chat with Jess, because all that was the backdrop to my life when I met Hannah.

I must have been stocking the shelves when Jess came downstairs that day. Before I could make one of my jokes to her, I saw someone standing behind her, unsure of where she should be or what she was supposed to be doing. She had gold rimmed glasses, brown hair tied up in a ponytail and was wearing a bright pink fleece.

‘Alistair, this is Hannah,’ Jess said. ‘This is her first day so show her around and try not to scare her off.’

I don’t know if other people feel this way, but some people’s voices are nostalgic right away. Just the tone of it evokes something in you, as if you’ve always known it in some far-off place in your heart. It sounds hopelessly sentimental or even a little insane, but that’s what Hannah’s voice did to me.

Maybe I’m just a beacon for mockery because most people seem comfortable when they’re chiding some aspect of my personality. It took less than an hour before Hannah was mocking me for getting up early, telling me it’s what ‘old men’ do.

‘Okay grandpa,’ she used to say, not so much smiling, but beaming from her eyes.

‘So you’re one of those people who think it’s cool to lay in bed till twelve every day?’

‘Obviously.’ She rolled her eyes and put her hand to her heart.

‘Don’t you love the mornings?’

‘Not as much as I like to sleep.’

‘People aren’t made for sleeping.’

‘Yes, we are,’ she giggled. ‘Otherwise it wouldn’t be so easy.’

She continued her assault throughout the shift, moving from my sleeping habits to the music I liked, before going after my literary tastes.

‘You like such depressing books.’ She blushed as she laughed, as if embarrassed at expressing herself so much.

‘I’m not a depressed person.’

‘Then why do you read those things?’

It was a good question. I didn’t really have an answer.

‘Well, what do you like to read?’ I asked.

‘I don’t want to read something which is going to make me unhappy. I mean, look at this stuff!’ she said picking up one of the books I had picked out. ‘Cancer Ward? It doesn’t set you up well, does it?’

‘I’m sorry but that is a beautiful book.’

‘How?’

‘I can’t answer that.’

‘What do you mean?’ she asked, shocked and enjoying her surprise.

‘I can’t say what makes it so beautiful. Even if I could put some words to it, it still wouldn’t… you can’t feel it unless you read it.’

She lowered her eyes and smiled. ‘I can’t read a book like that.’

She didn’t lie like most of us do and say: ‘Oh I’ll definitely read it.’ And neither did she pretend she found it all interesting. See, she had this silent confidence to her. I might have made her sound boisterous and loud but she said everything in a muted but deliberate tone. Just two hours before she had been almost hiding behind Jess and now here she was, saying everything unabashed, as if it was all just a statement of fact and the natural way you ought to speak to anyone.

Her and Jess liked ganging up on me. I remember I had to write a note to attach to one of the books and both of them told me off for having scruffy handwriting.

‘Your “c”s look like “l”s,’ Hannah said.

‘And your “t”s are nothing like “t”s,’ Jess joined in. I don’t know, isn’t there something wonderful in all that? To have someone who feels close enough to you that they can mock you freely?

‘You need some colour in your wardrobe,’ Hannah said, pulling at my top once. ‘You wear a black t-shirt every week.’

‘Are you the fashion expert?’

‘Obviously.’ She rolled her eyes and rested her hand on her chin. She always wore bright colours – pink, green, yellow – all of which made her skin shine.

We used to chat for hours. Sometimes our manager would come downstairs and give us some task, and I would be reluctant to accept if it meant we had to be separated. If you had asked me why, I would’ve said it was because I enjoyed talking to her and that she was good fun, so why go back up to the stuffy storeroom when I could stay downstairs with her? All of this was true, of course, but was it the truth?

Hannah always made me laugh but I couldn’t recall to you a single joke she made. The funniest people never have jokes to hand. It’s always in the way they tell a story or they react to certain things and this, unfortunately, you can never really convey to other people who haven’t met them. I have an image of her giving me this funny look when some rude customer approached her, as if to ask: ‘Are you seeing this?’ I can’t describe the look but I felt like it said so much, even though nothing changed but her eyes.

Now I walked to every shift with a vague anticipation in my chest. I knew something was there, something that I felt to be important and meaningful. And for some reason, I wouldn’t link this feeling with Hannah. If I thought of her, I’d smile, but only because I’d feel relief that I’d enjoy my shift and have someone to talk to. I couldn’t think of the bookshop without thinking of her. I made more of an effort to look good and was overly careful about how I conducted myself in the shop. I didn’t admit my feelings for her but then why was I so desperate to impress her and have her think me cool, witty and smart? That’s a funny one – why did I care about being smart? Intelligence had little to do with it. I used to think intelligence would make people swoon but I soon realised people aren’t bowled over by it all that much.

Now her reproaches and jokes sent little sparks through my heart. If she smiled or laughed or twinkled her eyes, I’d notice it and feel a joy that was so concentrated and momentary that it almost hurt. I walked home with that private smile we have when some secret pleasure has taken a hold of us. At random moments during the day, when I was out walking or just before I was trying to sleep, I’d think of her and out of nowhere, my heart would start beating as if she had actually just walked out in front of me and I was now on the spot, forced to say something. I’d go to the pub with friends and would try to imagine her there as well. What would everyone think? What would she think of me? You know, one of the subtler ways we try and impress others is by talking about our friends. I thought that by hearing what I did with them and by telling her stories that she might think me the kind of person who was adventurous and daring.

I remember a customer asked once if one of us could help carry some boxes from her car. It was raining outside and she made a joke about me being the one to go outside. I was happy to do it.

‘Oh no, I was only joking,’ she said, looking shocked more than anything.

‘It’s okay honestly,’ I said, placing my hand on her arm for a second. In that moment I had all sorts of thoughts about the future, about life, about everything that goes on out there and in here. What moves us? Why do we do what we do? How did my life go to come to this moment where I might place my hand on her shoulder? Why not romanticise the trivial? I’d rather look back on my life knowing I was the sort of person who sought beauty even in the simple moments of life rather than being one who understood it all in the way a mechanic might, pulling it apart until it no longer resembles something with any sort of purpose.

On that same rainy evening, a Christmas party had been scheduled for anyone who volunteered at the shop. I remember scanning the list to see if her name was there and I couldn’t find it.

‘You’re going right?’ I asked Jess, being too scared to ask Hannah directly.

‘Yeah. Hannah, aren’t you going?’

‘I didn’t sign up in time,’ she said, shrugging her shoulders. A smart man would’ve suggested that she came anyway and that it wouldn’t make a difference but for whatever reason, I said nothing. You see, that would have made everything perfect and I probably would have been able to put a name to my feelings if she had come. Jess and I had a fun time, drinking, eating, laughing, all in a way that we never could in the store. There’s something about finally seeing someone you work or study with outside of your common routine, as they are, when they are only there to be social and have a good time. Then I wondered what it would have been like to have had Hannah there as well… to have her reproach me, laugh with me, tell me her stories, everything that I loved so much…

When the party was over, I walked home rather than taking the bus. I imagined everyone knew what I was feeling but was just choosing to ignore it. I walked slowly, not caring about the cold, at moments stuck in my own head and at others, painfully aware of everything going on around me. I’d see the warm orange glow of people’s living rooms, the wreaths on people’s doors, the faint sigh of traffic in the distance. I was thinking about all sorts of things: the book I was reading, the song I’d been listening too, the tartness of the wine I’d been having, but all of these came back to Hannah, as if they were all somehow connected to her and my feelings towards her. What did wine and books have to do with those gold rimmed glasses? Why did I keep thinking about the rain and that heavy box I had to lift?

That night I threw myself on my bed and let my thoughts run for hours. I remembered one shift where Hannah and I were arguing about what we thought books were for.

‘I love fantasy books, as you know,’ she said, even then implying that I had a duty to know everything about her. ‘But I don’t like them when they’re all fairy tale-like and all about happy endings. Life isn’t like that.’

‘That’s a little pessimistic.’

‘Life isn’t a fairy tale.’

‘Perhaps not… but that doesn’t mean it has to be this cold, dark place.’

‘You really think that?’ She did that thing with her eyes, that little thing I can’t explain, which used to send a rush through my heart. Honestly, her eyes must have been very strong for the amount she rolled them. ‘All your books involve people complaining about the meaning of life and how nothing ever works out for them.’

‘I like books which show us how life really is.’ I stopped for a second then spoke quickly, as if my words might be swallowed up before I could get them out. ‘And what’s more bleak? A book which has to lie about the world to make it look rosier? Or one which shows you how tough life can be but makes you appreciate the beauty in spite of it?’

She stopped for a second and looked me dead in the eye.

‘I think we want different things out of books,’ she said, smiling, and in her smile was every implication that I was wrong.

A moment later, another memory overtook me, of another shift where I got was muddling up which books were new and old, which ones needed pricing and which needed to be thrown away.

‘I’ve made a real mess of things,’ I told her.

‘You can’t be very smart then,’ she said, pouting.

I smiled. ‘I guess not.’

These memories merged with all sorts of thoughts from another time; all my loves, crushes or ‘feelings’ of the past. I thought of how much I had felt from afar and how little I knew of the world. I’d never had that joy of sitting with a girl and being able to hold her hand. I imagine it sends a fire through your chest but I would say that wouldn’t I? My image of love comes from novels. It would still be better than how I felt then, lying on my bed, chained up with my rabid thoughts. That much I knew. I thought about some of the people I knew at university, the least romantic ones, the most cynical or pessimistic. Many of them had been in love before and had held hands or shared a kiss in the park. Didn’t their hearts move as well or was it all just another small pleasure in this cruel life we have?

What was my conception of love at that time? I had a philosophy which I could express consciously, that it was a powerful force which took hold of people, against their will. But what did I really believe about love? What idea had my mind developed over the course of my life? Love had never worked for me. It was always from a distance; the sort of thing I would sigh about in secret. Love was not holding hands or kissing or looking in one another’s eyes. Love was centred on me and some distant person because my love had never been mutual. In my eyes, love was this painful feeling which took hold of you and left you yearning for something greater in life, something you knew was not open to you.

‘But why should it have to be that way?’ I asked myself. ‘Life is given to me as much as it is to anyone else, so why can’t it be romance and intimate gazes for me as well?’

That’s when I understood that I should just ask her out. That’s not so hard, is it? Ha! It’s not so hard to say but for many of us, it feels nearly impossible to do. Being the kind of idler I was, I planned it out rather than resign myself to fate and let it happen organically. For some it may be easy to just see her and ask, as if asking upon which shelf the crime novels should go. I had to construct a perfect scenario in my head and never came to anything satisfying. Every moment was inappropriate. There was no good time to do it. Suppose Jess was there as we were leaving the store – should I ask Hannah in front of her? What if I invited them both? That would be too casual. What if I asked in the middle of the shift and she said no? How could I continue to work then?

I had become completely at odds with the world. Sometimes I’d be walking down the street, so preoccupied, I’d bump into someone having not seen where I was going. The romantic in me tried comforting my sorrow by seeing myself as a sort of Romeo. ‘We are most busied when we’re most alone.’ That’s what the greatest love story ever told said. And there I was feeling the same. What do you suppose that did to my feelings? Perhaps in the early days I could’ve smiled at such a line but now that I knew that something had to be done and that love shouldn’t just exist in one’s mind, the line felt useless and offensive, precisely because it was so accurate. What could I learn from Romeo about being in love? A million ideas are worth nothing compared to a single action. This is what happens when thinking paralyses you. You create lofty illusions around your sufferings, believing yourself as some sort of martyr or hero that everyone is waiting for to succeed. No wonder I was surprised by people’s indifference. How was it that all those pedestrians on the street could just pass me by, without any idea of the pain rankling itself in my heart?

What did I have to lose? Isn’t that the common line? There is a lot of truth in it but I felt I could answer straight away what I stood to lose. I’d look like a fool. I’d feel like a fool. I might have my heart broken when she said no. Should any of this have prevented me though? The only way that something might have come from my feelings was if I did something. Sitting around, there was only one way for the world to change, and that was for Hannah to come up to me one day and confess that she loved me. When you felt like I did, part of you really believed that might happen.

I arrived at my shift one day and the first thing I saw was Hannah talking to Jess. I felt an ache in my heart, I’m not exactly sure why. I remembered what it was I’d resolved to do that day.

That afternoon, while we stacked the shelves laboriously, Hannah was telling me a story about her friend.

‘So yeah, my friend said she’d call me but she kept delaying it and delaying it and eventually she says: “Sorry, I have to reschedule.”’ I was trying to listen but my nerves had their claws around me. At the end, when we were cleaning up, Hannah had finished her duties before me and left before I got the chance to say anything, not that I had much faith in doing it anyway.

I told myself that it had to happen next shift. All I had to do was ask her. I hoped that the fear of regret would be enough to prevent me from doing nothing. I worked myself up to it so much that I could barely think in the days prior to it and yet, on that destined day, I was surprisingly calm. I’d even forgotten what I’d resolved to do and when I remembered, there was no chill or rush in my chest.

‘The time will come and you will do it,’ I said to myself. ‘So long as you do it, you have done everything you can.’

I didn’t bother to scrutinise this idea but let it calm me. I still remember the walk to the shop. It was warmer than usual. The sun was out. I didn’t need a jacket. It was one of those days when you walk past people and want to give everyone a smile, not even because you are happy, but just so you might acknowledge that the two of you are there together to appreciate such a wonderful day. Every step closer to the shop, I refused to be disturbed by the task ahead of me.

‘Don’t think about it until it happens,’ I told myself and for the first time ever, I was able to control my overthinking. I’d see her and laugh with her, just as I had done before, and then everything would be easy.

I was a little late so expected to see her straight away, but all I saw were the silent faces of the customers, scanning the shelves with their blank, almost cruel expressions. Something was already beginning to stir in me, but I dismissed it.

‘She could be on the till,’ I thought but when I went upstairs I only saw Carol waving at me, rather than the gold rimmed glasses. Up in the storeroom? She wasn’t there either. Maybe she was just late?

‘Hey Ali,’ Jess said, popping her head round the corner. I don’t think I said anything. ‘You okay?’

‘I’m good.’ I stopped for a second. ‘Is Hannah in today?’

‘I’m not sure. Check the list.’

Her name had been crossed out for every week. I’m not lying when I say I felt a physical pain in my chest, like it had been stuffed with ash. Was she away? Had she quit? The realisation that I might never see her again clawed at me. I remembered the last week I’d seen her, how I’d hesitated when we said goodbye, how she gave me a confused look and smiled. Suddenly it all seemed so deliberate and meaningful but what did any of it mean? I looked over the storeroom, now so small and suffocating. Jess stood humming, sorting through a pile of books, completely indifferent to everything going on in my heart. How could she be so calm about it? Didn’t it bother her as much as it bothered me?

I walked back downstairs like a zombie.

‘Hello Alistair,’ Finn said, limping in as he always did. ‘Can I leave my…’

‘Yes… of course,’ I said trying hard to smile.

‘You know I re-read The Razor’s Edge the other week. Have you read it?’

‘I…’

‘It’s a marvellous book you know. It shows you what the West has to learn from the East. That title is from the Bhagavat Gita. There’s much to learn about life from it, more than the Bible I’d say.’

I can’t remember anything else he said. There was a ringing in my ears, blocking out everything, and forcing my mind to focus on one image, and image which already had that faded, spectral quality our mental images have. Sure enough, Jess and I had our chats and our jokes, but I did it all with an ache in my side. I’d be laughing at something she’d said and suddenly remember Hannah, feeling her absence as if it were filling the room, choking me.

‘She’ll be back,’ I told myself. ‘She would’ve told us if she’d left.’

Every week I expected Hannah to be there. One time, there was even a girl who looked like her and I had to look again. She caught my eye.

‘Are you okay?’ she asked. Her smile was actually very sweet.

‘Yes, sorry. I just thought I… saw something.’

She made a face as if to say: ‘Don’t worry.’ Part of me believed she knew what I was thinking but how could she? It was all just some strange trick my mind played on me.

Now when I went to the shop and saw Jess or Carol or Finn, I felt a kind of bitterness, as if their presence was somehow responsible for Hannah’s absence. Only then did I realise how irrelevant it was to know whether my feelings were love, attraction or something else entirely. All I really wanted was to be with her, to laugh with her again, to have her tell me how ‘out of touch’ I was. I’d give anything for another reproach. I don’t want to forget any of it. They tell us to pick ourselves up and move on but towards what? You know, I’d walk through the park and the flowers would grab my attention against my will. They’d bring back a memory, which must have only been a few weeks old but felt like it could’ve been from when I was a child, of Hannah wearing a flower in one of her hairpins.

‘What kind of flower is that?’ I asked, desperate to have any kind of conversation I could.

‘I don’t know. I just pick out the ones I like.’

I wanted to tell her it looked nice but I couldn’t.

‘Have you seen my new badge?’ she asked, pushing towards me a little pin on her jacket of a purplish cat. ‘Isn’t it cute?’

‘Very cute.’ I felt like I blushed.

Whatever is in your heart stains the world. If you felt the way I did then the flowers and the grass weren’t just there, cowering under your feet, but were there because someone else was there and they had to make the world more beautiful to match it. Ha! How could I think all these things and not think I was in love? Why do we delude ourselves like this? Why can’t we face up to the truth? We don’t cope with love by working at our jobs or reading books or just pretending it doesn’t exist. It’s insulting. We don’t tell someone whose starving that they ought to go for a walk to clear their head. Sure, they might feel blissful for an hour but their stomach is still empty and there’s only one thing to do about it.

Only now did the idea of asking her for a drink or a coffee seem so simple. What world would I be living in now if I had just said it? It was all so simple, wasn’t it? Now that I had this distance between myself and the person I could have been, it was so clear what was missing. One action would’ve outweighed the world. It was so easy. Wasn’t it so easy? But isn’t this just the trick of regret? Isn’t this the game of hindsight or the illusion when we philosophise? We discuss human nature in the way a scientist discusses an ant, but how close can we get to actually being the ant? When will we understand the ant’s struggle? I pride myself on my observations and my ability to understand the motives of people but what good is that if we still do nothing with our knowledge and continue to make the same mistakes?

I still walk down the high street hoping to bump into her. Would I have the courage to ask her then? You’d think I’d have to now given everything I’ve said but who knows? I can easily see a world in which I see her in the street, she smiles, calls me grandpa again, and then walks off without us ever seeing each other again and I’ll be in the same position as I am now and all the more miserable for it.

You know, if there ever was a sin in this world, it’s to do nothing. Don’t sit around and wait. I might try and soothe myself by thinking everything is okay and that good things come from patience but so often I want to throw all that away and squeeze everything out of life that I can. Why stand around? Why be cautious? Where has our sensibility ever gotten us? Imagine the world where Hannah isn’t a memory but is actually with me, right now? I don’t know whether that world was possible but it never could be when I lived the way I did. Why are some of us so afraid to take chances? Why do we want everything handed to us? We weren’t made to sit around. I once believed we were and I missed my opportunity. She’s still there somewhere, probably close by, so close that I might see her out my window one day. Maybe she’ll come back into the shop and tell me to get some proper clothes again or that she’s come round to reading books with happy endings or that life really is some great fairy tale after all… Perhaps it does me more pain to think that way. Down the road or far away… it’s all the same now. I think, while those gold rimmed glasses still have a place in my heart, I’ll have to content myself with only a memory…

For more short stories, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.