Quicksand

You were there long before I took the form of a {man}. Before I began to steal shapes out of my pregnant {mother}, and before adolescence stole back shapes out of me. You, my grandfather, have always been a man. Stoic and sinewy, you emerged from the delivery room five feet and eleven inches tall and you remained that way until the day you buried yourself at the back of the garden, between the two birch trees.

I saw you that day from the window in my {mother}ʼs old room. While you were pruning the hydrangeas that crawled their way up the corner of the house, I was trying on one of her dresses. I shrunk and spun into the fabric, discovering new corners to my {body}. She had not slept in this room for years and it had been turned into a guest bedroom, which made it feel doubly unoccupied, even as more people graced its sheets than ever before. The surfaces were littered with the usual detritus of a childhood. Unlike you, I was privy to the double-life of these objects, the way these hangers-on are cherished by a parent, but to the one fleeing home, they are all the bits left behind.

I caught your eye in the mirror. I have no idea how long you had watched me there from the doorway. It was as if you’d pruned your way up the side of the house, slid in through a crack in the window and across the room. The strange, angular joy I had found in these garments boiled up into a hot panic and I pulled off the dress to reveal, underneath, the protruding ribs and loose-fitting boxer shorts of an eighteen-year-old {boy}.

‘Do you think that this makes you a girl,’ you said, not really asking at all. The word girl came out of your mouth barely complete and it crumpled to the floor, lying limp next to the clothes scattered across the room. I knelt down and began to fold them up, quietly apologising to each one, stepping over to the open dresser to return them, but I barely took two steps before you wrestled the fabric out of my hands. The drawer shut and you gestured to me, still in my underwear, to leave the room, closing the door behind me.

You always had a fascination with the earth. As if the tidy rows of shrubs and trees that made up your garden had anything to do with that elemental force from which all life springs, or with that great yawning earth that swallowed your {daughter} two springs before. Perhaps I am too cynical. Perhaps you dug up little secrets out there that you wouldn’t tell me, like the ones I found woven into the seams of my {mother}ʼs dresses,

tiny ghosts

tumbling out

of fraying

edges…

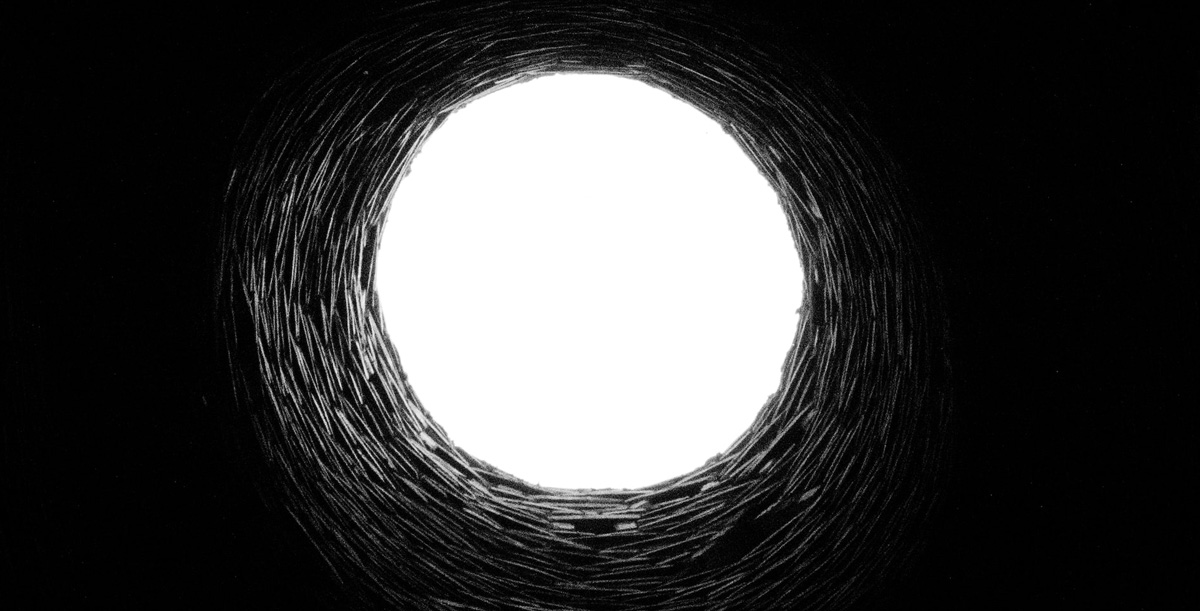

I don’t know how long you had been digging the (((hole))) when I found you. ‘Looking for treasure?’ I said to your back. Already shin-deep, you grunted without turning your head. The soil was wet from yesterday’s rain, and it clung to the mottled silvery bark of the birch trees as you tossed it aside. I wore my large black hoodie that swamped my {body}, familiar and formless. My boxers bloomed out below and then my bare legs sinking slowly into the earth.

I walked back inside, not stopping to wipe my feet, and watched you through the kitchen window, folding yourself into the ground, suddenly aware of how old you had become. You had always been old, but during my teen years, it had felt briefly like I was catching up as you marched me into adulthood with quiet triumph. A puff on your pipe at twelve, a glass of watered-down whisky at thirteen, and so on; these tiny harms became my rights of passage. But the ritual grew stale during those last years of my {mother}ʼs life. There was no joy left in the passing of time, and not for want of trying. I remember our calendar in that last year, filled to the margins with all sorts of festivities of her own contrivance. She was usually too tired to carry any of them out but I can still see her, sat in bed, coffee on the dresser next to her painkillers, pencilling in plans for my ʻfifteenth and a half birthdayʼ, time churning at her feet.

The wet earth gave way without complaint. Soon, a ragged tangle of birch roots became exposed, reaching out to your legs as if they were beckoning you deeper. Your knees began to rub against the walls of the cavity and you were forced to expand the diameter, scraping away at the edges with the shovel. I watched you coil round the edges, like a pupa chewing away at its cocoon. The steadily growing mound of displaced soil behind you made the (((hole))) seem even deeper than it was.

‘Are you burying something?’ I said from the French windows that opened onto the garden.

You paused, shifting your weight onto your left leg before turning to face me. ‘Burying,’ you repeated. You wiped your brow with the back of your hand and it left a great grey smear above your right eye. ‘I’m sinking here.’ I was silent, for some reason reluctant to state the obvious. ‘The ground’s going to swallow me up.’

‘Well stop digging,’ I said.

‘The (((hole))) just keeps getting wider, {son}. Wider and deeper.’ You looked up at the house, before turning and attending to the left side of the (((hole))) with renewed concentration, as if there were some unutterable method to your thrusting and jabbing.

I returned to my room and turned up the TV to drown out your grunts and groans. My legs, filthy from the garden, reached out of my hoodie and stretched over the edge of the bed. They were slim and downy and awkward. My size ten feet always seemed surprised to appear at the end of them – my least favourite feature. They anchored me to a {form} that wished to race away from itself just as it threatened to turn into something large and horribly familiar. But when I lifted my legs up and pointed my toes, examining them in the mirror as I would sometimes do, I could feel for the briefest of moments elegant, intentional.

Eventually, the labours of your digging became audible above the noise of the television. I peered out the window. You were facing the birch trees, and although I could not see your face, it was clear that you were panting like an injured wolf. You jabbed at the ground with the heel of your boot but it did not budge. And again, several times, to no avail. Capitulating to the hard recalcitrant earth, your spade was tossed aside and you sank into the (((hole))) that you had dug for yourself, pressing your knees tight against your torso.

In a fury, I pushed the window open and yelled. ‘Stop it, for god’s sake.’

‘I’m being pulled down, {son},’ you said.

‘You’re doing this to yourself.’

You spun your head round like an owl and glared, not at me, but at the house. ‘This is what is happening and this is how it will be, my {boy}. And since you aren’t willing to help, can’t you at least be afraid for me?’

*

I wear dresses sometimes. Not very often and certainly not as often as I would like. Mostly I wear them on nights out, or at home, around my friends. I have often fantasised about wearing one when I come to visit you at the nursing home. I know exactly which one I would wear. It is a long burgundy floor-length gown with padded shoulders, a high neck, and ruffles down the font. It is a ridiculous garment by any measure and sometimes I wonder if I even like the way I look in it. I have only worn it twice and both times I have taken photographs in the mirror and then deleted them the next morning. Nonetheless, I like what it does to a room. The way the fabric folds up as it tickles the carpet forces people to circle around me, and although I am met mostly with looks of affectionate ridicule, they are looks nonetheless.

I have played out the scenario in my head, the recoiling, the embarrassment, the disgust, the anger, the shame. I have practised all of my rebuttals and I have practised them again. But each morning I plan to visit you, I open my wardrobe and I push all my garments aside (even the less feminine ones) and I reach for the same baggy turquoise sweater. It is not a bad sweater, but over the weeks and months it has become the sweater that I always wear to visit you and because of this, it belongs to you.

Our visits are not unpleasant, far from it. I enjoy our conversations about the garden, about how the other residents are too feeble, too confused or too stubborn to help you trim the hedges. Your cynicism has always been charming from a distance, even as I remember how suffocating it can become up close. I enjoy cooking for you, and not just because I feel bad for the state of the food you are forced to eat. I wonder if you put up with that place out of some twisted form of self-abnegation or because part of you is still putting money aside for two generations rather than one.

I am ashamed to admit that I enjoy your company now more than I ever have. In the nursing home, you feel like a grandfather once again. I am able to censor myself, as a grandchild often does. I curate and select. I wear the same sweater. I do not wear my gown. I had often thought as a teenager that this was a peculiar curse of youth, that each generation goes out into the world and finds something new, and then conceals it from their elders for fear of what it might do to them. But I no longer believe this. I sense more and more that you have unearthed something in your old age. I doubt I would even recognise it if it were spoken aloud, but at each visit, after we finish eating, after the dishes are washed and put away, after the card games are won and lost, there is a silence unlike any I would share with others my own age. I observe you shrinking into this inviolable (((gap))) that opens up between us, wishing only that you would speak as you

vanish

away from me

like a coin

tossed

into a well.

*

You pulled back the soil mounded up around the outside of the (((hole))) towards your body. It was a slow and clumsy process. After you had covered your legs and torso, there was the task of burying your own arms whereby each motion risked uncovering as much as it concealed. At one point, I almost offered assistance before I remembered exactly what you were trying to achieve. But after several minutes of careful scooping, and with the generous assistance of gravity, you managed to worm both of your arms into the ground, such that only your neck and head protruded out of the earth.

‘What happens next?’ I asked from the kitchen door.

‘I don’t know,’ you said blankly. You were still facing away from the house, towards the birch trees, motionless for the first time that day. The tree to your right had begun to bear the fledgling buds of spring blossom, which would soon fall and litter the lawn. The other looked dead. The layer of soil separating your shoulders from the early evening air could not have been very thick, but from the house, you looked as if you had been there for a long time; you had become part of the landscape.

‘What are you waiting for?’ you said, after a very long time.

‘I’m waiting for you to come back to the house.’ This was not entirely true. Part of me did want to see you rise up out of the (((hole))) and sheepishly slip back as if nothing had happened. But a much larger part of me wanted to see what would happen if you never left and, more importantly, what I would do. Would I try to pull you out of the ground? I wasn’t sure if I had the strength.

I dragged a white plastic chair across the patio and lined it up directly behind you so I could follow your eye line. An hour passed. Then another. The evening shifted and shuddered into dusk and soon, it was impossible to tell from your silhouette where you ended and the earth began. The sky above the houses was blotched orange and pink, muting out into an expansive navy above our heads. Distant, an aeroplane rumbled across the darkness and I shivered.

‘Do you think you missed out, not having a father?’ Your words punctured the silence. You have a way of posing your own thoughts as questions. Perhaps you think it is more diplomatic than stating them but I have always felt like our exchanges resemble more of a job interview than a conversation – not just because I feel like I am under fire, but that I am constantly searching for the answer that will please you the most.

‘I had you.’

‘I can’t be your father and fill in for your {mother}, {son}, not at the same time. Although maybe I should have tried.’ You paused, and I could see the shadow of your head flinch. ‘Now we’re both trying to be her.’

‘That’s what you think you’ve been doing?’

‘Well,’ your voice suddenly apologetic, ‘I just mean that I’ve been cooking for you, doing your laundry, cleaning up after you.’

‘And what would you have done different as my dad?’

‘I would have shown you how to be a man.’

‘Ha!’ I leapt up from the chair, causing it to fall over. The noise of brittle plastic on stone rattled across the garden. ‘Do you know how ridiculous you sound right now?’ I marched over to the end of the garden, round the edge of the mound and stood between the birch trees, so that we were looking at each other. ‘Is this the kind of man I should aspire to, or did you have something else in mind?’

You tilted your head away from me in shame, and some of the earth shifted exposing your right shoulder. ‘I know I must seem pathetic to you.’

‘Right now you do.’

‘But this is how it’s going to be. I have no other option but to remain here.’

‘No other option,’ I repeated.

‘I am what I am, {son}, tonight and always.’ You closed your eyes.

*

Mum got up from the bed and walked across to the window. ‘Another beautiful day,’ she said, peeking at the light through the net curtain but not opening it. I stood up from the armchair where I had spent the previous night and started to move towards the kitchen to fix the three of us breakfast. ‘I’ll do it,’ mum said, placing her hand on my cheek and kissing my forehead.

You were at the door and we exchanged a glance as she passed you on the way to the kitchen, gently trailing a hand along the wall for balance. The community nurse was due that afternoon and mum had developed a habit of trying to feign independence before her arrival. I stood at the door to the space that had once been our living room. In a few short months, it had become mum’s bedroom, her dining room and sometimes her bathroom when she was too exhausted to make it to the toilet. There were days when she was able to leave bed but they were increasingly followed by several days where she was not, and we started to meet moments like this with hushed incredulity.

We sat down at the table and tried to remember our roles, as {son}, as father. Mum scooped a second egg from the frying pan onto my plate. ‘Growing {lad},’ she said and we all agreed, a pantomime family, forgetting itself. You noticed that mum had not served herself any food, just a cup of milky tea. You said nothing for a moment, savouring the last few seconds of our little routine.

‘You need to eat something.’

Mum, who was about to take a sip from her mug, paused and put the drink down, as if it had suddenly soured. ‘I ate last night,’ she said. ‘I’ll have something for lunch,’ she hastily added, sensing your dissatisfaction. ‘Have some more, darling,’ she said to me. As she reached a trembling arm across you to slide some more toast onto my plate, she knocked over the jug of orange juice with her elbow, spilling it all over my plate and ruining my breakfast. Gasps and then sighs. ‘Here, take your granddad’s,’ she said, pushing your breakfast towards me.

‘I’m fine, honestly mum,’ I said recoiling from the table.

‘The {boy}ʼs fine,’ you grumbled as mum took my juice-soaked plate and moved towards the kitchen sink. But in all of the confusion, she managed to catch her ankle on a chair leg and tumbled over, the plate shattering upon impact. Mum let out a grunt as she hit the floor. For a second nobody moved, us all too collectively embarrassed or too tired. Her skin looked almost translucent, splayed across the kitchen tiles. Then, you rushed to help her up but she shrugged you off, and pulled herself to her knees.

Mum examined the kitchen floor. ‘What a mess.’

‘It’s okay,’ I said. ‘We’ll clean up the plate.’

‘I’m not talking about the floor,’ she said. ‘This whole kitchen is filthy.’ She was right. We had let the house fall into a state of disrepair over the last few months. The countertops were gritted with the remnants of meals half cooked and barely eaten, and the bins had not been taken out in weeks.

‘We can clean,’ you said.

‘The {boy} has school to be getting on with.’

‘He’s alright.’

‘I don’t mind helping,’ I interjected.

‘I can do it,’ mum said, frowning.

‘Maybe you should get back to bed. The nurse will be here in a few hours and I’ll have a little clean before she gets here.’

‘It’s not about that,’ mum said. ‘Do you think I’m just acting houseproud?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’m still his mother,’ she snapped.

You nodded. It was a statement only true in part. There were days when we let her be a parent. She would hear you scorning me for voicing some adolescent sentiment or other and she would chime in from the room she slept in, tssk-ing from beneath the bed sheets, and you would defer authority to this voice at the end of the hall and say ‘listen to your mother.’ And I would. But then I would have to come in and check in on her, or bring her a hot drink, or wash her body, and the exercise would become undone once again. We broke her down into a series of partible bodily functions that could be handled independently of one another. There was a quiet solace in this disassembly, but on days like this, I could only feel guilty at the indignity of it all.

I started crying but you whisked mum away into her room before she could comfort me. She went, reluctantly. When you came back, you were crying also. I opened my mouth to speak, but before I had a chance to say anything you pointed down to the bins.

‘Can you take those out on your way to school?’

‘Yes, grandad.’

Her {body} in motion

stopping

belonging to nobody else

and then to nobody,

and

(((nothing)))

at all.

*

I woke up on the sofa. From the milky light flooding through from the kitchen, I could tell it was still early. I exited the back of the house and paced across the side of the garden. Underfoot, the grass was swampy wet, the aftermath of downpour in the night. The sun ducked low behind the house and the garden was contorted in shadows. I circled around to the front of where the neck met the earth, the living birch tree behind me to my left, the dead one to my right. The figure did not move at the sound of my footsteps. Eyes were shut closed and a face was motionless. My first thought was not that it had died but that it had turned into stone, calcified, the skin blue-grey mottled like granite.

I spoke {grandad} twice but there was no answer. Extending an arm outwards, I lightly pressed my finger into the forehead. The skin wrinkled, holding the shape of the indentation briefly before settling back to its previous state. I half-expected the head to roll off, down the side of the mound of earth that encased the torso and into the grass. One eye opened. It beaded around before settling on my face. The expression did not change. The eye looked at me as if I were a stranger, or a part of the garden. The eye then looked past me, to the birch trees, following the trunk of the dead tree up to the sky and then shut, squeezed tight, then relaxing back to the original stony expression.

I repeated the figureʼs name. Once again. No response this time. I suddenly felt dizzy. I realised I hadn’t eaten since breakfast the previous day. My legs felt weak and I lowered myself to the ground, down into the mud, my back leaning against the living tree. I gazed up at the house, at the window to my {mother}ʼs room, and I shut my eyes, my mind shrinking away from itself. I dreamt of your silhouette, enormous and rising above the rooftops like a mountain, receding beyond the horizon even as I tried to approach it, running and sinking.

My eyes opened seconds later. I had left this world for an interminable instant but now I was back and your body seemed small, modest. My legs sprawled out in front of me and they were filthy from their contact with the ground. I stared at my muddy feet, stretching one leg up and straightening my toes. I knew what I had to do. I raised myself up, steadying my torso for a moment against the living birch tree, before striding back to the house. Opening the wardrobe in my {mother}ʼs room, I pulled out a dark blue, floor-length gown that I had seen worn only in photographs.

The garment was fitted, holding a shape even as it hung empty on the hanger. I filled it with my {body} as best I could. Tight across the shoulders, the fabric hung loose at the breast, and at the hips, the (((gaps))) between me and my {mother} hanging all around me. Clutching the empty places between our bodies, I made for the garden. Gliding down the stairs and out the door, I was liquid. The fabric dragged, pulling through the claggy earth, but it was as if I was above the ground, floating, not so much moving, but expanding.

‘Look at me,’ I declared.

You prised open your eyes and fixed your vision on me, scanning down my torso, studying my frame, my muddy feet. I saw a familiar panic rise up, imploding, simmering down to disgruntlement and bitter confusion. ‘What are you?’ you said after a long while.

I was renewed by the sound of your voice. ‘I don’t know.’

‘You can’t go round doing things like this when you don’t know,’ delivered with misplaced conciliation.

‘I don’t know yet.’ You sniffed at my comment. ‘Did you know what you were at my age?’

‘There was nothing to be known,’ rolling your eyes.

‘I don’t believe that.’

‘Do you want to be a {father}?’ you asked, once again laying down your thoughts as questions like a series of traps.

‘Maybe. One day,’ I replied.

‘Like this?’

‘Did you always want to be a {father}?’ I asked.

Remorse crossed your brow. Wriggling in the dirt, approximating some kind of change of posture, you tried to begin several sentences before giving up, defeated. ‘What do you want from me, {son}? Coming out here, dressed like that, interrogating me. Do you want my permission? Is that it? Do you want me to say I’m okay with you carrying on like this?’

I shrugged, intuitively wanting to say no. ‘Yes, suppose I do.’

‘I can’t honestly give you that, {son}.’ I turned away, suddenly aware of how tall I was, leaning over you. You sighed and tilted your head down. ‘But you’re grown now, and I can’t stop you. But you can’t ask me to like it.’

‘I’m still growing.’

‘No, you’re eighteen. I watched you grow up. I was there. Don’t you remember? You’ll have to stand on your own two feet now. If this is the choice you’re going to make, then you have to accept that as an adult.’

‘What choice? I haven’t made any choice.’

‘Aah,’ you roared, rolling your eyes back into their sockets with theatrical disgust. ‘It’s the bloody indecision I hate the most.’

I bent down to your eye line, moving my mouth only inches from yours. ‘I never noticed it before,’ I said softly, ‘but you’re getting older by the day. When I saw how stiff you were, digging yourself into this stupid (((hole))), I barely recognised you.’

A tear hung glistening beneath your eyelid, but you withdrew it before it had a chance to break across your cheek. ‘You never looked once like her,’ you said, only whispers now. ‘Even as a child, you never looked anything like your {mother}. You’ve always looked like your da.’

My mouth hung open. I reached forward to your shoulders and started to pull. Miniature avalanches began around your torso, cascading down the mound but I couldn’t get any purchase and the bulk of your body remained still. I put my foot up against the earth next to your waist to lever you outwards, sliding my hand down and tightening my fingers around your upper arm. You grunted, wriggling, trying to shake me off. I moved my other foot up so that my body was leaning out at a forty-five-degree angle, but then my fingers slipped and I let go, rolled backwards, bashing my head hard against a root sticking out of the base of the dead birch tree. The pain was blunt, heavy, the weight of my {body} hurled against itself. I reached a hand to the back of my head and I felt warm. You saw that it was blood before I did. Not changing the expression on your face, you shuddered from side to side. The earth began to tumble in large clumps away from your form, the shoulders and then the waist and then your whole figure exhumed, rising up from the ground and blocking out the sun, reaching down with both arms towards me.

*

It had only been a short trip to hospital, four stitches nestled in the back of my scalp, but I was sore and shaken. You drove me home, restless in the driving seat, fiddling with the radio. I stared out the window, letting the vibrations of the tyres against the tarmac numb me into a doze.

Back at home, you headed straight to the fridge and began chopping onions, while I perched at the kitchen table. I studied the grain of the wood, sinking a fingernail into a recess that had started to open in the oak. For a second, I thought I heard the sound of music, playing quietly or very distant, but as I leaned into the sound, I realised it was simply the steady hum of the kitchen lights, lilting in counterpoint against the throbbing of my head. It felt like I was on a film set, that with a firm push, the walls would fall away from me out into empty space, revealing nothing but a tangle of electric cables. My time was up in this house.

We ate dinner on the sofa in front of the television. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see you squirm around with the food in your lap, sighing into your spaghetti as it evaded the movements of your fork. You pushed the remote towards me, nodding with generosity and I obliged, switching the channel away from the programme I was quietly enjoying to something far less entertaining. You grunted with approval and so I put the remote softly back onto the arm of the sofa.

Later that evening, you helped me undress for bed. Together, we stretched the top of my sweater over my head like an elastic halo, avoiding contact with my stitches. I covered my chest with my forearm and you dutifully turned your head away. Crawling into bed, you pulled the duvet across my back, crumpling me into the cotton. Then you stood back and placed a hand on the bedpost and held it there. I felt the firm embrace of your grip through the bed.

A tiny prosthetic

intimacy, played out in

linen and pine,

(((vanishing)))

into the muffled concussion of

sleep.

*

I put on my facemask and examine my gloomy reflection in the glass of the door before ringing the bell. The sweater drowns out the shape of my {body}, smuggling my curves into its anonymous silhouette like stolen goods. One of the staff opens the door and squints with her eyes from behind her mask, signalling a smile, stepping back to let me in. I show the man behind the desk my lateral flow, though he doesn’t ask for it, and he laughs, nodding me through the double doors to the right.

I count the doors to your room, four, five, six, seven. Inside, the window is flung wide open even though it is October. You move, stand up to greet me but I take a cautionary step back, and as a reply, you pull the facemask strapped round your chin up to cover your mouth but not your nose. I can see the bristles of your moustache peaking above the blue and white. It has been four months since I last saw you but it could be four years.

You place a curled roll of notes on the dresser and tap it twice with your knuckles. ‘You don’t need to do that, grandad,’ I protest. ‘You know I have a job now.’

‘Nonsense. I want to give you something.’ You wipe down the notes and I pocket them, reaching for my hand sanitiser afterwards, a precious exchange of futility.

‘I see dirt under your fingernails, grandad.’

‘Oh yes,’ you chuckle. ‘But they’re all outside now, into nature all of a sudden and the like. Couldn’t keep them away from the geraniums with a shitty stick.’

I laugh and try to carry on the joke but you struggle with a response and I wonder if the line was rehearsed. ‘How are you otherwise? Are you keeping well?’

‘Yes.’

I ask about the carers, the food, the other residents. I worry that I patronise you but you go along with the questions, entertaining my civility without hesitation. After an hour or so, the game is up and there is nothing more to say. I make to leave but we falter at the moment when we might have embraced, wary of the distance travelled by our breath. Standing up, we perform a cumbersome little bow. You lower your mask to smile and I gesture a wave across the room. (((Silence))). But then, just as I turn to leave, you open your mouth to speak.

‘The other day when I was digging in the new flower beds over there by the greenhouse,’ you say, hesitant. ‘I was sure I saw you {both} walking in the rose bushes…’

((( )))

shhh… can you hear it?

‘{Both},’ I repeat.

‘…you looked so young, the {pair of you},’ you mumble on. ‘Like you was kids…’

((( )))

‘…you was only there for a split second and then gone again, disappeared behind the hydrangeas…’

((( )))

‘…I followed the {two of you} through the flower beds but when I came out the other side, all I saw was two of the carers, on their lunch break. They’re all so young, you see…’

((( )))

‘…it did make me chuckle though…’ Your lips remain straight, unsmiling. You turn your head and gaze out through the open window. ‘I thought to myself, that’s strange, seeing you {both} out here…’

you must feel it too.

((( )))

‘…{neither one of you} ever cared much for the garden.’

I let you walk me to the front door of the home as if the whole building belongs to you. You move slowly now, with a stick. I have to steady my pace considerably so as not to stride ahead. As I move, I keep my arms folded across my chest, twizzling the fibres of the sweater between my fingers. At the door there are more goodbyes. I do not want to leave but there is no good reason to stay and so I get into my car, still waving, and drive away, keeping the radio off, hush settling into the vehicle like a bad smell. As I pull out onto the main road, the gold hoop earrings I put on this morning catch my eye in the rear-view mirror, dancing in the muted autumn light, coiling shadows across my cheekbones. They are much larger than the pair I wore last time.

*

Some (((gaps))) do not need to be filled. Some may never be. Some (((gaps))), though they may seem to stretch on forever, are simply the empty spaces we have not yet flowed into, only discovering the full extent of their size once we have bloomed beyond ourselves, beautiful, strange and inhabited. But the hole you left behind was not any of these. It looked small without you in it and it did not take long to cover over. With three or four broad gestures, you pushed the earth to the side of the birch trees back into the cavity and patted it down with the sole of your boot. Together, we rolled out a fresh section of turf. It was a different colour to the rest of the lawn, carving out a perfect rectangle against the mulchy green, still waiting to be dragged out of winter into spring. A year later, the new grass would be seamlessly assimilated into the texture of the garden, and a year after that, the whole lawn would be torn up by the new residents to build a conservatory. I have visited that neighbourhood once since you left, and I could still see one of the birch trees in full blossom, hunching over the garden fence, rattling against the windows of the new construction like it was asking to come in.

I stood in the centre of the new piece of grass, like a chess piece waiting to be moved. The future stretched out in front of me across the garden, looming above the house, formless and huge. I knew I would be leaving soon. I looked down at the grass between my toes and saw that the freshly packed earth was subsiding slightly under my weight. I stepped off and lowered myself to pat down the grass again but I hesitated, comforted by the faint impression I had left in the ground.

For more short stories, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.