I Wouldn’t Be Here Without You

Day two

I dread to think how many flies I’ve swallowed since we came here. The air boils with them so that you can hardly breathe. They find their way through the mesh on the cabin windows. They swoop on uncovered food. Their corpses collect under lamps and in the plastic shells of ceiling lights. There’s one on me now, drinking from a droplet on my arm. I blow it off, but it only lands again a moment later.

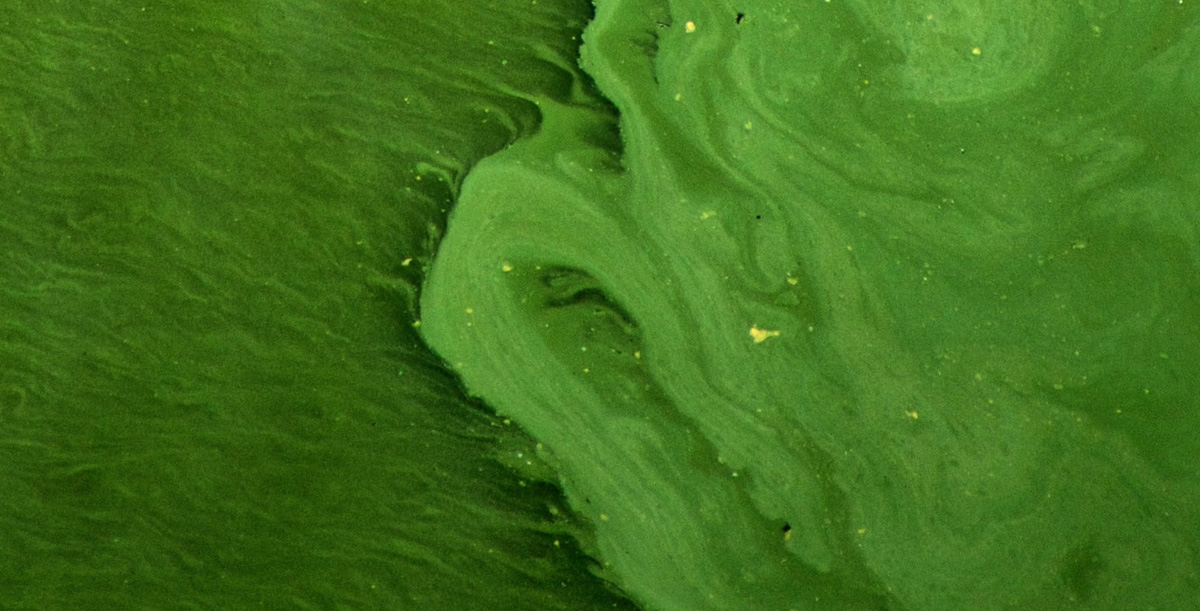

I look away, towards Sophie, towards her body crammed into its black swimsuit and those telling marks on her arms. She’s bleached her hair. Isn’t she worried about the water getting inside the strands, tinting them as green as the algae-ridden bathing pond she insists on swimming in? Green as the wall of cornstalks at the edge of the resort. Green as the Tyrolean mountains, which loom over everything like tsunamis frozen in time. Green as an old bruise. Green as the varicose veins in Sophie’s legs as she turns in the water.

‘Come on,’ she says. ‘It’s refreshing.’

Refreshing is another word for cold. I’m happier here, on my lounger, questioning why I let my sister talk me into this trip.

We’re supposed to be reconnecting; mending the relationship that ended five and a half years ago with me telling her she’d ruined my life, and her telling me I’d never had one. She says she’s doing better now, as if a haircut and a holiday at her expense is enough to convince me of that.

We’re the only Brits in the resort, as far as I can tell. The babble from around the pool is an incomprehensible mix − German, Italian and some others I don’t recognise. I like to script their conversations in my head, to make up lives for these swimwear-clad strangers. There’s a man on the far edge, who I christen Georg. Georg is tall and chiselled and tanned the colour of toffee. He’s watching a golden-haired boy in armbands splash across the pool.

‘Super!’ Georg calls. He smiles, revealing a crescent of straight, bright teeth. He says something else, which I decide means, ‘I wish your mother was alive to see this.’

Sophie and I used to have a game like this as children. We’d decide that a man across from us on the bus was a foreign prince. A woman at the launderette became a Mafia boss. The school caretaker was an undercover talent scout, out to recruit the next big star.

Georg is a modern artist. He takes pictures of nude women, and sometimes men, then wraps giant prints of these photographs over mannequins. It’s a statement about beauty standards or something. I imagine he might look up at any minute and see me and think how perfect I would be as a model.

But his eyes are fixed on Tomas. That’s the boy’s real name; I know because Georg keeps using it. Ja, Tomas! This way, Tomas! I’ve never seen such aquatic prowess, Tomas!

Tomas paddles towards his father, grabs onto his leg, and begins a feeble attempt to pull Georg into the pool.

‘Oh no − you’re too strong for me!’ Georg slides into the water ducks his head under. When he resurfaces, his hands are wrapped around Tomas’s middle, hoisting him into the air while he turns and makes rocket sounds.

Tomas is an only child. He’ll grow up with everything he ever wants and become an astronaut or an Olympian or a world leader. He doesn’t know how lucky he is.

‘Phew!’ Sophie flops down, shedding flecks of algae-water. ‘It’s chilly once you’re out.’

‘The sun’s stronger than it seems.’ I root through my bag until I find what I’m looking for. ‘You should put some of this on.’

‘Thanks.’ Sophie takes a squirt of sun cream and rubs it into her damp skin. There are tiny bits of green stuck to her, like mould. A fly buzzes by her face and she flinches.

I think it’s the smell that draws them. The far side of the resort borders a cluster of livestock sheds. The stench, a cocktail of faeces and rancid flesh, is like nothing I’ve experienced. There are flowers lining every path in the resort − planted, presumably, to combat what blows over from the farm. It’s a strange contradiction: to see the log cabins and the trees and the archways trailing roses, and to smell that dreadful, animal rot.

‘Isn’t this wonderful?’ Sophie gazes at the mountains. ‘You couldn’t dream a view like that.’

‘It would be nicer without the flies.’

‘Yes.’ She laughs. ‘They must like sun cream.’

The insects do seem drawn to her today, more than usual.

‘Yeah,’ I say. ‘Maybe.’

A wail cuts across the scene. Tomas is cold or tired or hungry. Georg helps him out of the water and holds him against his chest, but this does nothing to quiet the screams. Georg hurries towards our loungers and the gate on my left.

‘I’ve named him,’ I say to Sophie. ‘Georg. And the child is Tomas.’

‘Shh,’ she hisses.

Georg passes in a flash of toned legs and I’m faced with Tomas’s siren mouth gaping over his shoulder.

‘Relax. We’re never going to see them again.’

*

Day four

Halfway through our trip and we’ve ticked off almost all the activities on the resort’s list, though it feels like holidaying with a stranger − albeit one I’ve shared a bathtub with and who I still put down as my emergency contact on forms. It’s a sunny day and Sophie decides she wants to go for a hike.

‘It would be a break from these mountains,’ she says. ‘I feel like I’m being watched all the time.’

We take the cable car up and grab a map from a stall which also sells postcards, bottled water and souvenir versions of the cowbells that chime every now and then across the hillside.

‘I read those are really unethical,’ I say. ‘They deafen the cows.’

‘Oh.’ Sophie’s forehead puckers. ‘I didn’t know that.’

We set off along a route marked ‘medium difficulty’. The path curves uphill, through sloping pastures, wild grasses and wind-twisted shrubs. After a while there aren’t any turnoffs, but I keep the map open anyway. It’s a good excuse to interrupt Sophie when her prattling gets too cowbell-like in the way it clangs against my ears. Or when I need a breather. I’ll put my hand out and gesture vaguely at a distant peak.

‘That’s Ellmauer,’ I’ll say, or Nordekette, or something else that sounds convincing and means nothing to either of us.

‘Really?’ Sophie always feigns interest. She’s holding up remarkably well. Even as the path steepens into uneven rocky steps and sweat pastes my fringe to my forehead, Sophie keeps a steady pace and absentminded smile.

I keep watching for signs of the little sister I knew − like the way she’d fidget, knotting skinny fingers in her sleeves − but she’s not there. Her fleece is pushed up her forearms. Her hands hang steady at her sides. To think she used to struggle up a flight of stairs.

‘Mark introduced me to yoga,’ she says. ‘I don’t know if you’ve tried it?’

I don’t care.

‘Honestly, I’ve never felt better. I’m thinking about marathon training − I know it’s a cliché but—’

I don’t care. I don’t care. I don’t care.

At the peak, we find a wooden cross and scatter of crows pecking at the ground. Sophie sits on a boulder and I go to look at the view, mostly to prove I can. My legs feel like driftwood.

Where the path ends, there’s a steep drop-off with a brook tripping its way down, then the treeline like the start of an avalanche. Below that lies the whole valley. It snakes through the mountains; a slumbering creature scaled with houses and church tower spines. Lakes are green eyes in the forest. The river glints like a needle. And the sky − I’ve never seen a sky so large, so all-encompassing. There are clouds the size of continents, circling the valley like a drain. I can breathe here. The flies are gone.

‘Wow,’ Sophie says at my shoulder and I jerk back, away from the drop.

‘I wasn’t going to push you.’

‘I know,’ I say, annoyed. ‘You just surprised me.’

*

Sophie’s quiet on the way back, which suits me fine. I’m wondering what she’d do if I told her I’m done; this isn’t working and I’m tired of playing along. I don’t know why I came in the first place. I don’t know why I didn’t hang up the phone as soon as she said, ‘Hello? It’s Sophie,’ like I always told myself I would. She suggested this trip and I wanted to say no. I wanted to tell her I was too busy. My life was full up. No room for her. I pressed the phone to my mouth like I could swallow it.

‘Bother,’ Sophie mutters. Her hands are cupped beneath her nose. ‘The bloody altitude.’

‘Bloody’ is the right word. I find some tissues in my bag and pass them to her, one by one. Nosebleeds aren’t unusual for Sophie; she knows to tilt her head forward, not back, and pinch at the bridge. She finishes off my whole pack of Kleenex. They sit in her lap like crumpled roses.

*

Day seven

Sophie is packing, folding t-shirts into tiny squares and laying them in her suitcase with meditative precision. I’m sitting on my bed and watching. Most of my things never left my bag, so I don’t have much to do.

There’s a knock at the door and I jump up like I’ve been waiting for it. Standing on our cabin’s porch is Georg. Up close, I can see the meltwater-blue of his eyes and the crevice of worry between his brows.

‘You are English?’

‘Yes.’ I say it like a confession.

‘I am looking for my son. My small boy? He has blond hair. He is this tall.’

‘Yes.’

‘Have you seen him? He might have gone by − he likes following the pathways.’ Georg is blinking too much, pushing back tears. A fly zips past him and over my shoulder, into the cabin. Then another.

‘No,’ I say. ‘Not today, I mean. I haven’t seen him.’

Sophie emerges from the bedroom just as the door is clicking shut. ‘Who was that?’

‘The man from the bathing pond. He’s looking for his son.’

‘What?’

‘His kid has wandered off. He asked if I’d seen him.’

Sophie blanches. It’s the first time I’ve recognised her since we arrived.

‘We have to help,’ she says. ‘Who knows what could happen to him?’

He could be kidnapped. Killed. He could fall in the bathing pond or the river. He could fall in with the wrong crowd. He could find a syringe and stick it through his skin.

We rush into our jackets and shoes, though by the time we’re through the door Georg is out of sight.

Sophie isn’t giving up. ‘Come on. You go that way and I’ll head towards the village.’

She says it with such authority that I start walking in the direction she points. Perhaps she really is a teacher, though I’m amazed they let her.

I move between the cabins, scanning for movement. A towel hanging on a veranda might be Tomas’s yellow t-shirt. A bird landing could be him crawling by the rose bed.

What a way to spend our last day. For all we know, Georg already found his son and Sophie and I are out searching for nothing. That would be fitting: to end the week chasing something we’re too late for and are never going to find. What a waste. What a waste of time. I’m only here because I needed to see for myself. Blond, teacher Sophie…

A fly catches in my hair and I smack it away with surprising viciousness.

Did she really expect me to fall for it? After everything I sacrificed? My youth, my sleep. Covering for her. Cleaning up her mess. Wiping the puke from around her mouth while she laughed at nothing. You worry too much, Mel.

The cabins smudge at the edges of my vision but I’m walking faster, sifting for a child’s cry beneath the rustling breeze and insect whine. Maybe I will find the boy. That would show her.

To call me up, no warning, like a voice from the afterlife − of course I didn’t believe it. The new job? The boyfriend? The blue-painted house on the seafront? They were as real to me as Georg’s mannequins; real as the stories we made up together as kids.

I turn a corner and there’s the bathing pond, iced with scum. Could Tomas be in there? No − he couldn’t get past the fence − but once the thought is there I can’t escape it. I can taste the algae clotting in my throat like I’m the one floating face down. The light shifts, catches a yellow slice of water − and for an instant I freeze, convinced it’s Sophie’s hair.

‘Mel!’ The scream pierces through the green and my head snaps round. ‘Mel!’ it comes again, from the far side of the resort.

I run without thinking. That voice has hooked onto something I thought I’d lost, and I have to get to her. I have to. I’m running into the stench, towards the pens and fences and barbed wire. The flies are thicker here, bouncing off my face like hailstones.

Vault the gate. Skid over the mud. Hear the child’s cry. Look up and see them.

‘I found him,’ Sophie says. There’s shit in her hair, on her clothes, and she’s smiling.

Georg stands beside her cradling Tomas, all three of them bathed in filth like a monstrous nativity scene. Tomas’s cries have softened now, and I can hear the soft German Georg is pouring into his ear. I don’t feel like inventing a translation.

I take a step and my foot slips from under me. I’m lying on my back in the dirt, looking up at Sophie’s stranger-face as she offers me her hand.

*

The smell follows us back to the cabin. It seems to radiate not from the mess on our clothes, but somewhere deeper, on the inside. Flies buzz at my ear and I don’t bother swatting them away.

‘Stefan said he’d buy us drinks,’ Sophie says.

‘Who?’

‘The man whose child we helped find?’

‘Oh.’ His name is Stefan and he’s probably not an artist. ‘Do you remember that game we used to play, when we’d invent stories about strangers?’

Sophie frowns. ‘Vaguely.’

I let her shower first. As the water runs, I stand in the bedroom doorway. I need to take my shoes off − they’ve already tramped dirt into the cabin − but I can’t bring myself to do it.

I think of Tomas, back in a safe warm place. Georg will wash him, cover him with bubbles, rub shampoo into his fine blond hair and hope that it’s enough.

There’s Sophie’s suitcase, lying open on the bed with all her things neatly packed inside. We’ll catch a flight tomorrow and Sophie will go home to her blue house and her boyfriend. I’ll go home to my empty flat and an inbox full of customer complaints and I hate her. I hate her so much I can’t stomach it.

On top of the suitcase is a white shirt. It gives under my touch, cool and soft. My finger leaves a faint grimy smear. I peel back the white layer and press my palms into the clothes underneath, ball them up, wrench them out and throw them to the floor. Tread foul, stinking muck into the fabric. I’m destroying her work, churning it up with my harrow-fingers − then something snags at my skin: a paper-edge, an envelope, unopened, with my name on the front.

It’s a card. Jesus Christ, she wrote me a card. There are pressed flowers glued on the front − did she make it herself? − and I’m trying to read what it says but the flies are too loud, and it doesn’t matter anyway.

For more short stories, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.