The Blue Rose

‘Everything you can imagine is real.’ – Pablo Picasso

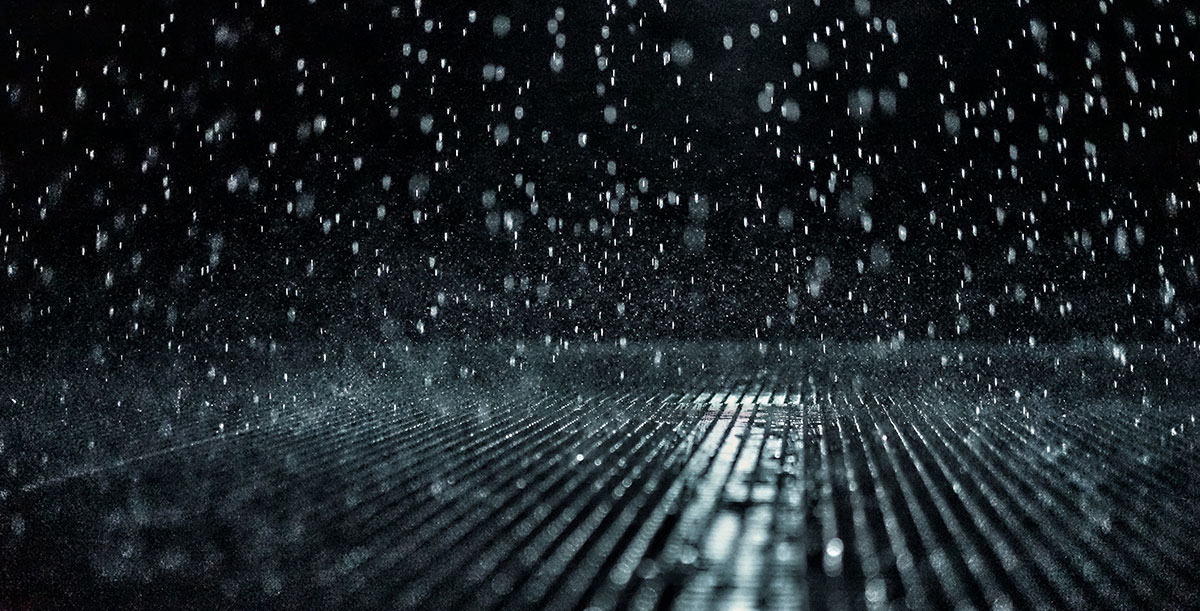

It must be Paris outside; I can smell the rain in the dirt between the cobbles.

‘When are you going to write a story about me?’ you ask, rising from the sofa. Your perfume mixes with the wet-grass scent of the room.

I laugh to myself and you laugh too.

‘When am I not?’ I reply. I can feel you coming closer, even though I’m trying not to look. You wrap your arms around my shoulders and place your cheek so it’s touching mine ever so slightly.

‘What’s this one about?’ you ask. You can read the computer screen over my shoulder but that won’t do you any good. The page is blank.

I don’t know yet, I type.

You don’t say anything.

After a while I turn but you’re gone. The room’s empty except for me and the lingering scent of your perfume.

I write without a destination, editing as I go, discovering my story and my characters with every new word I type. Sometimes I can see one of my characters in the corner of my eye, but they’re half-formed things, ethereal on the page and in my mind. They disappear when I turn around.

And I’m trying to ignore the smell of French toast coming from the kitchen.

You’ve been here for about ten minutes, maybe a little longer but not much. When you first got here you watched me write, sitting on one of the piles of books that rests against my living room wall, keeping quiet, not wanting to disturb me. But I knew you were there. Staying in the background isn’t your style. Even when you’re not talking you’re demanding attention. It’s in the little things you do, the way you flick your hair, the conviction of your attention, the control you exert over a room – you just have to be noticed.

‘Can’t you just give me one day? One day, alone, to write,’ I say as I walk into the kitchen. You’re frying toast in a blue dress, bare feet against the wooden floor.

‘It’s Paris outside, you know?’ you say to me, not looking up. I know it’s Paris outside. The scent of the rain still lingers on the street. Montmartre doesn’t smell like the rest of the world; you told me you could smell the stars at night, the first time we ate there. ‘We didn’t eat bacon, though,’ you add, reading my thoughts.

‘Why are you the only one who sticks around?’

Now you look up from the frying pan.

You smile to yourself and I smile too. ‘It’s as annoying for me as it is for you.’

‘How so?’

‘I think you should go into Paris today,’ you say, concentrating once more on the frying pan. ‘You don’t know when the door will open to Paris again.’

‘You want to get rid of me that much?’ I joke, but I’m a little hurt.

***

On the streets of Montmartre lived a man who grew roses in the dirt between the cobbles…

You’re hovering over my shoulder again, reading out loud what I’ve written.

‘Did you find someone?’ you ask, excited.

He wasn’t an old man but he had an old soul, a soul worn out from feeling too heavily. Every day he would sell a flower or two, and a flower or two would be trampled by someone every day. But that wasn’t the flower seller’s main concern. Greater things occupied his mind. Each moment he would pray to catch a glimpse of the woman he grew his roses for.

‘When are you going to write a story about me?’ I look up at your face and you’re smiling. ‘Tell me about him?’ you ask, walking away and collapsing onto the sofa.

‘He loves a woman – ‘

‘I know that. It’s you, of course he loves a woman. Tell me something else, something new. Tell me why he’s different from the characters in your other stories.’

I take a minute to think.

‘He’s dying,’ I finally say.

‘Is that so?’ you reply.

‘I don’t know how, not yet, but his clothes are too big for him, he moves too recklessly for a man of his fragile frame.’

I start typing again.

The doctor had given him four months to live, and a lifetime had come and gone since then. But even as he stood waiting in the rain, he kept one eye on his roses and the other, as always, on the lookout for her.

***

Usually, the door doesn’t open to Paris for another three weeks. I busy myself with other things while I wait. On the days it opens to Debrecen, I spend the evenings downtown in an old bar listening to the locals. Some of them speak English but not regularly and not clearly, although their superstitions are understandable in any language. Debrecen and Transylvania are too close for many to sleep soundly. On the days the door opens to Manhattan, I enjoy the bohemian lifestyle my agent begs me to cultivate for myself. My professional image. Not that it matters in Manhattan, no one notices me there; that’s why it’s the only place where I’m willing to play along.

And on the days the door opens to my home town, I close the door almost straight away and kill time around the flat, reading a book from one of the many piles stacked up against the wall, or listening to music and scribbling down notes in my old notepads. With every new city I visit, I miss the rural North a little more. I miss the smells of my childhood most of all.

‘What if your flower seller is trying to grow the perfect flower for his love?’ you say, moving across the room and hanging your head out of the open window. Again, your perfume mixes with the scent of the room, of the spring flowers and the sea nearby. You’re dominating the space once more, like you always do. ‘That’s why he doesn’t leave. It’s not that he doesn’t want to, but it’s like … like it’s his purpose, to grow this one perfect flower for the woman he loves, and until then, he can’t do anything but keep trying.’

‘What would this perfect flower look like?’ I ask you.

‘A rose,’ you reply, longing in your voice. ‘It would be a blue rose.’ Then you add, with a smile on your face just for me, ‘If this was my story it would be that.’

We sit and talk about nothing for the rest of the day, our legs crossing on the sofa. You’re at your playful best and I’m trying not to notice that your eyes don’t always smile when your lips do. When it gets cold I close the window, and when it gets dark I draw the curtains and turn on the lamps.

***

Paris is more than I remember; there are more stars out watching us tonight.

‘This way,’ you say, your arm reaching out for me.

‘Montmartre is this way,’ I argue, heading off in the opposite direction.

‘I know.’

And you keep going your way, not looking back, crossing the old bridge, passing the street lamps with the peeling paint while the wind plays with your hair.

‘Where are we going then?’ I ask, running to catch up to you and taking your arm. But you don’t reply and instead run your finger along your lips, sealing them.

The night is cool. We don’t pass many people but the ones we do pass have their heads low; they’re wearing dark suits, dark dresses. Paris is the kind of city that looks like it could have been painted; like it should have been painted; you can see the dazzle in the artist’s eye in the streetlights reflecting off the Seine. Even the air smells like an artist’s palette, of an artist’s palette and you.

You’re telling me of a time when you visited Paris before we met. You were young, you can’t quite remember how young exactly but it was back when your dad would still hold your hand and walk with you. The entire time you jumped between the cobbles on the streets as if they were lily pads, dragging him along with you, and every time you landed you’d turn to him, you’d smile at him and he’d smile back. You told me that a dozen times, each time like it was the first.

Your dad took you to see an artist he knew. He lived in an attic above a theatre where stage musicals played three times a day; the final show would start when the sun rose and keep going into the morning. The stairs up to the attic shook with every step, and you closed your eyes and held your dad’s hand as tight as you could.

He jostled you into the room, pushing gently on your shoulders and that’s when you opened your eyes, ready to brace yourself in case you fell, but instead you ended up staring at the most beautiful thing you’d ever seen; along the insides of the sloped roof someone had recreated the Parisian skyline and the night sky above it. In some places the paint was thicker, whites and blues and blacks all mixed together, layer upon layer on top of each other. In other places the paint was thinner, where tiles on the roof outside had cracked and the rainwater had seeped through. Sometimes weeds would grow up from the floorboards directly below. The artist told you that he had found it like this; that the attic was a sacred place for artists, here was where they gathered, where they lived when nowhere else would have them, paying for their lodging by maintaining the skyline.

Then he handed you a brush. There was no paint on it, you said, he’d just picked it out of a glass of grey water, and the water dribbled down your hand and left stars of paint down your forearm. The artist didn’t need to say anything; and your dad, he just smiled at you and you smiled back.

We step out of your story and we’re on the cobbled streets of Montmartre; our Paris is just like that. It looks like it hasn’t rained since I was last here, but the smell is still distinguishable in the dirt.

‘Let’s go find him,’ you say.

But I don’t move.

‘Come on.’

‘What if I can’t write about him?’ I say. ‘What if he’s not there, if he won’t talk to me, if he’s not the person I remember, if – ‘

In one swift movement you take my hand, you lean close to me, so close that our bodies are almost touching, so close… you lean in and pull me forward, and off we go.

Behind you is the night sky, just as I imagine you’d choose to paint it.

On the streets of Montmartre lived a man who grew roses in the dirt between the cobbles. I let the words play around in my head, let them dance and jump between the cobbles just like we’re doing. I invite them to find their own way through the streets.

‘This must be it,’ you say.

We’ve been walking for what barely seems a moment, but there’s orange mixed in with the blues of the sky so morning can’t be far away. Ahead of me I can see roses of virtually every colour sprouting from the streets, the same ones that caught my attention when last I was here. It’s quiet now. There’s a few stray cats purring on the rooftops; a couple of streets away there’s a musical coming to a close.

‘His house is around here somewhere,’ I say, letting go of your hand.

‘Can I pick one? Just one?’ you ask, but I’m already walking ahead of you, stepping carefully so I don’t damage any of the flowers. On either side of me the street grows narrower, shop windows slowly funnelling me down the slope and back towards the river.

‘Is that it?’

I look back and you’re pointing past me, to a door further down the street covered in vines. Tendrils of green and brown have wrapped themselves between the brickwork in place of cement. The roses in the street grow denser as I get closer to the house.

I pause when I’m in front of the door. My legs are weak. I can feel you close behind me, so close that your cheek is almost touching mine. You lay your hand on my arm.

I smile to myself; in my mind, you’re smiling too.

And I push aside the vines and open the door.

He’s there in front of me, the flower seller, upright in his lounge chair. His cart has been brought inside and it’s resting by the door, ready to be wheeled out again the next day. All around the room there are countless roses; roses of every colour but one.

There’s a hole in the roof and through it we can see the stars. That must be the last remaining patch of night time around and it’s looking right down at us.

He’s there in front of me but he’s not moving. His body is so small, so frail. I close the door in case the wind catches him and he drifts away like pollen. What’s most unexpected is that the room has no scent to it; it doesn’t even smell of your perfume.

‘I’m sorry,’ you say, kneeling next to him, and I don’t know whether you’re saying it to him or to me. But where your eyes are on the flower seller, mine are on what’s fallen to the floor at his feet.

Because there on the floor lies a blue rose.

***

‘You promised it would be ready,’ my agent sighs at me over the loudspeaker on my phone. The window’s opened wide but all I can smell is the scent of your perfume.

‘It will be, just… just not yet.’

‘Give him time,’ you shout from the sofa.

‘One more week. One more, and you’ll owe me for this. I hope you know that. I’ll have you signing books off Times Square with half a dozen scarfs around your neck, you just wait.’

‘Thank you,’ I say. She’s hung up the phone before I can thank her again.

‘You won’t be done in a week,’ you say to me.

‘I know.’

I stand up from my desk, playing with my hair, closing the window, moving towards you but pausing. Then I collapse onto the sofa alongside you, sighing heavily.

‘I don’t know how it ends,’ I admit. ‘All… It can’t end like that, it shouldn’t.’

I’m looking up at the ceiling. It’s dark; the only light we have is from the computer screen and the lamps in the corners of the room.

I’m looking up at the ceiling and, despite the cracks in the plasterwork where rainwater drips in from outside, it still looks like our Paris sky. Although it looks less and less like it each day.

You throw your legs onto the floor and jump up from the sofa. Your toes move as if playing a symphony.

‘Let me read it.’ From anyone else, it might have been a question.

I sit quietly while you read, my fingers unable to keep still. When you’re finished you don’t say anything, not straight away.

‘Well?’

‘He left the blue rose behind to wait for her.’ You’re quoting me, repeating my words and they sound better coming from you. ‘And there the rose waited, its stem growing brown and its leaves wilting, always on the lookout.’

‘What do you think?’ I ask.

You walk over to the window and run your finger along the petals of the rose that now lives on my windowsill, the flower the same shade of blue as your dress.

‘When are you going to write a story about me?’ you ask.

I laugh to myself and you laugh too.

Candlelight is another magical realism story from Greg Forrester.