Shield Eyes From Light

By John Barrett Lee

It was past midnight when I woke on the sofa, cold and stiff, the house finally quiet. The central heating had clicked off, and the usual sounds – Finn and Gracey clattering about like goats upstairs, the washing machine on spin, the background chatter of YouTube – had faded into stillness. Even Dougal, our restless terrier, had stopped hunting for spiders and tucked himself into his basket by the radiator. Only Jenny’s confession lingered, like the smell of burnt toast. Nothing could get rid of it.

Lit only by the Christmas tree, I crept to the kitchen. The tiles were cold underfoot, stealing warmth through my socks. Flicking on the stove light, I clicked on the kettle and dropped a tea bag into a mug, more from habit than desire. I stood there waiting, staring through the window at our long, narrow garden in the winter moonlight. It was all just the same. The cracked paving slab, the patch of lawn that never grew back, the buckled fence panel, the shed crouching next to the mossy, junk-strewn greenhouse. We had moved in soon after Mum died, a week before Gracey arrived.

Beneath the kitchen clock, the portable television, turned down low, was still tuned to the sci-fi movie channel. Jenny and I liked to watch it after bedtime stories and kisses had been administered, her with a Chardonnay, me with a beer. Her novelty glass, which read ‘Mummy’s Little Helper’, was still on the counter – lipstick on the rim, dregs in the bottom. Multicoloured paper strips lay scattered across the table from paperchain-making with Gracey. They’d fallen out of fashion, but Jenny still adored them.

She must have left the TV on when she went up early, both of us too tired to fight, too hollowed-out to talk. I’d only found out about the affair the day before – just a few messages on her phone. No name, no kisses. Just enough to know. I wish I hadn’t looked. But I did. We hadn’t argued. Not properly. Not with the kids home all day and Christmas looming. The words ‘mistake’ and ‘meaningless’ were said. ‘You weren’t there’ was also thrown my way. And I suppose I wasn’t, not really. Whole months had gone by when we’d spoken in logistics – nativity play, car tax, the vet’s bill, how Santa was meant to afford an Xbox. We were living like housemates. She’d said, through stifled sobs, that she didn’t want to break up our family over one stupid decision, but that she’d felt like a ghost in our marriage. Then there was silence. And waiting.

I fumbled for the remote, but then I heard the music – futuristic, yet steeped in orchestral grandeur from the golden age of film. I knew it instantly: Back to the Future.

It was midway through the first act. Marty and Doc outside a deserted shopping mall in the early hours, Doc explaining the flux capacitor, his life’s work. Testing the time vehicle on his dog, Einstein. I stood there, the room flickering blue and silver as the DeLorean ripped through time – the score swelling, my tea going cold. Something shifted in my chest.

I hadn’t thought about that Christmas in years – the one I spent in the flat-roofed shed, convinced I could build a time machine.

*

It was 1989, and I was nine, living with Mum in the same semi-detached house. Dad had left six months earlier. No one really told me anything then. Just slammed doors, raised voices and a long stretch of silence. I knew only two things: Mum cried when she thought I couldn’t hear, and someone called Debbie was to blame. Her name was spat out like a curse.

Mum held it together with Nescafé, tight smiles and long drags on Superkings Lights. She was heroic – a broken-hearted, single mother with two jobs and never enough sleep. Her hands were always busy – cooking, smoking, cleaning, writing in her order book – but her mind was mostly elsewhere.

Then one night, when Mum was out on her Avon round, I watched Back to the Future on HTV, alone on the hearth rug in front of our wooden TV. There, in the dark with a Ribena and a packet of crisps, I was transfixed. Marty McFly went back in time and fixed his parents’ relationship. Not only that, he made it stronger.

The next day, I took my saved-up pocket money to the Texaco garage on North Road and rented the VHS. I watched it again and again, studying it like a manual. I decided I’d do the same as Doc and Marty. I would build a time machine and fix my family.

*

The shelves of Dad’s old shed were neatly arranged with tools, tins of paint, jam jars of screws and washers, and boxed car parts labelled in his careful block capitals. He’d wired the place properly – nothing fancy, but a thick orange cable ran from a drilled hole in the kitchen wall, clipped neatly along the fence and into a junction box beside the door. Inside, a plywood board held a pair of sockets, and a workshop lamp was fixed to the ceiling.

I tugged on my thickest jumper – Nan’s finest, with a downhill skier on the chest – then zipped up my parka and pulled on Dad’s fingerless gloves. They hung loosely on my wrists, but they kept the cold off. My breath puffed out in clouds as I unfastened the brass padlock. Inside, I switched on the one-bar heater which buzzed beneath the bench with enough warmth to take the chill off, if you kept your coat on.

Then I set to work converting my ‘dandy’ – the soapbox car Dad helped build the spring before. He was a mechanic, so while most kids had rope to steer, ours had a proper wheel salvaged off a Reliant Regal. It also had a brake – just a wooden lever pressing a bit of tyre rubber onto one of the pram wheels, but it worked. The dandy wobbled, but it turned, it stopped, and when you tucked your knees in and let it run downhill, it felt like flying.

I scavenged whatever I could find: plywood, paint, my granddad’s broken Roberts radio, an old car battery. I didn’t think I was pretending. I thought I could really do it.

On the second day, Mr Ellis appeared.

He lived next door. A retired science teacher, Mum said, tall and carefully spoken, who wore a tie every day and once grew a sunflower taller than the fence. I knew his wife had died because a black hearse and limousine had pulled up one day around the time that Dad left, and then we didn’t see the cheerful Mrs Ellis anymore. I knew Mum sometimes brought him a plate of whatever we were having for dinner. If she’d had time to bake, she’d bring him some cupcakes or jam tarts, too.

He said he was there to return the football I’d kicked into his garden. He found me in the shed, sitting in the dark with wires around my knees.

‘What have we got here then, young Martin?’ he said, peering through the door.

‘A time machine,’ I told him.

He didn’t laugh. Didn’t ruffle my hair and call me ‘boyo’ or tell me to go and play outside. He stepped into the shed and said, ‘Is it nearly ready?’

*

From then on, he came by each afternoon, wearing his duffel coat and bobble hat, carrying two mugs of sweet, milky tea and a packet of custard creams or ginger nuts. He helped me think through switches, draw schematics in my notebook. He even brought over a soldering iron. He never talked down to me. He called me ‘Engineer’.

The shed smelled of solder and pipe tobacco. Mr Ellis sat on the upturned crate by the door, pipe in one hand, tea in the other, watching me with that calm, unreadable expression he always wore when I was ‘engineering’.

‘Did you build anything like this when you were my age?’ I asked one afternoon.

Mr Ellis sucked on his pipe. ‘My son, Charlie,’ he said eventually, his voice quieter than usual, ‘was good with machines. He had this way of looking at something and seeing exactly how it should go together. He built a burglar alarm for his bedroom door when he was ten. It nearly gave his mother a heart attack when she went to change the sheets.’

I laughed. ‘Is he an engineer?’

‘He joined the Navy after school – said he wanted to see the world. We come from a long line of sailors, anyway. And battleships, systems – it suited him down to the ground.’

Mr Ellis reached out and straightened a coil of wire on the bench. His hands were steady, precise.

I looked up from dismantling the radio. ‘Where is he now?’

He paused and tapped the stem of his pipe against his teeth. ‘You’re probably too young to remember the Falklands.’

‘Aren’t they in Scotland?’

‘They’re way down in the South Atlantic. A group of rocks with more rain than Pembrokeshire.’

‘Nowhere near Scotland, then.’

‘Not very near. But Britain went to war over them.’

‘Why?’

‘Argentina invaded. Claimed the Falklands were theirs. But most of the islanders disagreed – they wanted to remain British. Mrs Thatcher decided that was worth fighting for. And maybe it was.’

He gave a dry little shrug. ‘Flags, speeches, newspaper headlines. She talked of “our boys.” But they weren’t her boys.’

The back of my neck prickled. He struck a match and relit his pipe. The flame flared briefly, then dimmed as he drew in the smoke.

‘Was Charlie there?’ I asked, suddenly not sure I wanted to know.

Mr Ellis stroked his white moustache. ‘Charlie was serving on HMS Coventry as part of the task force. The ship was bombed and sank in twenty minutes.’

I looked down at the radio parts in my lap. ‘I’m really sorry,’ I said quietly.

Mr Ellis looked at me then placed a hand softly on my shoulder. ‘Thank you, Martin. That’s kind.’

‘For a while after,’ Mr Ellis continued, ‘I used to imagine he’d washed up somewhere. Patagonia, perhaps. Or some tiny island no one had thought to check. I would picture these battered old postcards arriving months late, saying ”Plenty of penguins and icebergs here. See you soon.”’

He smiled, not with amusement, but something quieter. ‘Grief plays tricks with time,’ he said softly. ‘You start looking backwards instead of forwards. But time doesn’t care which way you’re facing. It just keeps moving.’

He glanced at the half-finished cockpit, where I had rigged up old bike reflectors with a drill and cable ties.

‘That’s why I like what you’re doing, Engineer. I think your approach to the energy flow here is promising. And if we can stabilise the particle field before Christmas, well – who’s to say where you’ll end up?’ He passed me the torch. ‘Now, show me where you’re housing the flux capacitor. If we want this thing operational, we’d best not dawdle.’

*

The next day, Mr Ellis turned up with a surprise.

‘I’ve booked us tickets,’ he grinned, holding up the film listings page of the Western Telegraph. ‘The sequel. It came out this week.’

‘Really? Part Two?’

He nodded. ‘We’ve got to stay up to date with the science. I’ve checked with your mother, and she agrees that you deserve a Christmas treat. Showtime is at seven o’clock, which is past your bedtime I expect, but as it’s the school holidays, an exception can be made for such a momentous event.’

For the rest of the afternoon, time seemed to run in reverse. That evening, we caught the town circular to the theatre. I wore my jeans, checked shirt and puffy red gilet, looking as close to Marty as I could manage. I sat bolt upright through the whole film, Mr Ellis beside me with a box of Fruit Pastilles, offering me the black ones without asking. There were hoverboards, flying cars, a dystopian present, a trip back to 1955 to save the world, Silvestri’s score swelling and soaring.

When we stepped out into the cold, the high street was slick with rain, orange streetlamps glowing in the puddles and Christmas lights swaying in the wind between the lamp posts. My head was buzzing – with energy, with hope.

‘If we boost the flux capacitor,’ I said breathlessly, ‘with two batteries instead of one…’

Mr Ellis just nodded and smiled, his scarf flapping in the wind. At the bus stop, he asked, ‘What would you do if it worked, Martin? If you really could go back?’

I looked at the pavement. ‘I’d stop my dad from leaving.’

He said nothing. Just reached out and rested a hand on my arm, gentle as a tap of rain.

*

A few days later, the machine was finished, and it was a beauty. The whole vehicle had been spray-painted silver, then wrapped in a roll of turkey foil to help conduct the energy field – quite what energy, I wasn’t sure, but I knew copper helped, so I’d coiled as much wire as I could find around the frame. I’d also built a crude plywood cabin, covered in bicycle reflectors, to stop me getting ripped apart in the vortex.

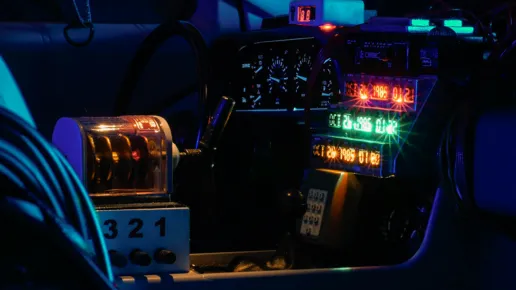

A rope light from my dad’s days as a wedding DJ was wired to a car battery and tied to the front of the cockpit to initiate the wormhole. On the dash – a bit of two-by-four screwed across the struts – I’d taped my mum’s kitchen timer for countdowns, and our Tandy calculator to input the destination coordinates. Several dials from the broken Roberts radio were fixed between them, mainly for monitoring temporal fluctuations.

But the pièce de résistance – the core of the whole apparatus – was the flux capacitor. Mr Ellis had built it inside a square biscuit tin, painted with grey primer, with a clear window cut into the lid so you could see the inner workings. Inside, three empty pill bottles were arranged in a perfect Y-shape, each containing a flashing red LED powered by its own 9-volt battery. Copper wire looped between them in what he called ‘inductively plausible circuitry.’ And on the side, in raised white capitals on a bright red tape, was a label from his handheld printer: SHIELD EYES FROM LIGHT.

When the lights pulsed in sequence, the whole thing glowed like a living heart. I remember just staring at it, not blinking. If anything was going to work, it was this. Mr Ellis helped me bolt it behind the seat and we were ready for launch.

Still, one problem remained.

‘We need plutonium,’ I told him. ‘Or a lightning bolt – that’s what powers the time machine in the film.’

Mr Ellis looked thoughtful, then slipped off his wristwatch – an old one with a cracked leather strap and scuffed face with thick numbers that still glowed faintly in the dark.

‘Radium dial,’ he said, handing it over. ‘Mildly radioactive. That’s how they made the numbers glow in the thirties.’

‘Is it dangerous?’

‘Only if you sleep with it under your pillow for thirty years,’ he said. ‘But I estimate it has just enough fission energy to power the time circuits.’

I held it like a treasure. ‘Where did you get it?’

‘A gift. After finishing grammar school in 1937,’ he said. ‘A Rotary. My father saved up for six months to buy it.’

‘Won’t you be needing it?’

‘I got a Casio digital one last Christmas that I ought to start wearing,’ he said. ‘In any case, I’d always meant to pass it down.’ He stroked the edge of the Rotary with his thumb, his fingers resting on my hand. ‘I want you to have it, Martin. You’ll need an accurate watch on your journey.’

I turned it around in my hands once more, then carefully placed it inside the biscuit tin flux capacitor.

*

The next morning, I pulled on my ski suit and wellington boots to protect me from radiation and wheeled the time machine to the top of the steep concrete slope outside our house. This led down to the electricity substation on the grass below, and it was where we children sledded when it snowed.

This was it. T-minus two minutes.

To my surprise, Mum was already there, arms folded tightly against the cold, her cardigan too thin, the tip of her cigarette glowing red in the pale winter morning.

‘Do you really think this’ll work, Martin?’ she asked.

‘I don’t know, Mum,’ I said. ‘But I have to try.’

She didn’t laugh. She just looked at me in that searching, slightly pained way she always did when she thought I couldn’t see her. Then she dropped her cigarette, ground it under her foot, and forced a smile.

‘Alright then,’ Mum said. ‘Let’s see this thing fly.’

A moment later, Mr Ellis arrived, red-faced and breath billowing. ‘Apologies for the delay,’ he said, producing a stopwatch and a clipboard. ‘All systems calibrated? Mission ready, Engineer?’

Mr Ellis and Mum stood there, huddled near the tree, as I wheeled the vehicle into position. I boarded her and flicked the switches. The rope light and flux capacitor blinked into life. I punched the destination date – the day before Dad disappeared – into the calculator and set the countdown timer for ten seconds.

‘Ready to commence countdown!’ I called.

‘Go on, son,’ said Mum softly. ‘Make it count.’

Mr Ellis struck a match with a flourish and lit the two sparklers taped to the frame, added to boost the ignition sequence.

I started the countdown: ’10, 9, 8, 7, 6…’

I pressed play on my Matsui tape recorder. The Silvestri score crackled through the speaker, triumphant and urgent.

‘5, 4, 3, 2, 1!’

I kicked off and hurtled down the slope, the rope light flashing and sparks streaming behind me. Faster and faster – nearing eighty-eight miles an hour. I closed my eyes, gripped the steering wheel, and…

The vehicle slowed to a juddering halt in the long grass by the substation.

Nothing had happened. No lightning. No interdimensional rift. Not even a smoking tyre.

I was livid. At myself. At Mr Ellis. At everything.

I ripped the cabin off the dandy and stormed home, angry tears streaking my cheeks, as Mum followed me back to the house in silence.

When Mr Ellis knocked in the afternoon, I told him it had all been a stupid game. That he should’ve known better. That he was just a silly old man wasting both our time.

He didn’t argue. Just nodded and left me alone.

*

The next day was Christmas Eve. I found the time machine back in the shed, the cockpit reattached, the damage repaired. A sheet of continuous, perforated paper – the kind Dad’s old dot-matrix printer used – was folded into an envelope shape and taped to the flux capacitor. I opened it carefully. The pale-green stripes, the sprocket holes down each edge and the slightly fuzzy letters made it look official – almost scientific. The fresh ribbon ink smelled of hope and possibility. I sat in the cockpit and began to read.

Dear Martin,

If my calculations are correct, you will receive this letter shortly after you activated the time vehicle. Congratulations! The event was a success. The tear in the space-time continuum, while too small to allow full transit, was sufficient for me to send this transmission to you.

I’ve been displaced – not lost, just held in a distant point on the timeline. There are forces beyond my influence: gravitational pulls, closed circuits, barriers I can’t override. I don’t know if re-entry will be possible.

But please understand – this was never about a failure in your engineering. You made something real with your hands and your heart. But even the most elegant designs can’t override the conditions around them.

Still, I monitor the signal. I track your path from afar.

Remember, Martin: energy doesn’t vanish. It shifts form. It travels. And some bonds, once created, persist across time and space.

My love for you is one of them.

— Dad

*

And suddenly, thirty-five years had passed.

The next evening, I found what I was looking for stacked away in a corner of the shed, its cardboard sagging with age and caked in dust and cobwebs: a box marked ‘Martin’s Stuff’ in my mother’s neat handwriting. Shivering, I pulled it out and lifted it onto the workbench.

The letter was still there, pressed inside the yellowed pages of the Back to the Future: Part II novelisation, wedged beneath a folder of school reports, Amstrad games and plastic Ghostbusters action figures. The once-pale stripes had browned, and the dot-matrix text had faded, but the words were readable. I sat on an old kitchen chair and read.

By the time I finished, I was crying.

I sat in the shed a while longer, the letter open on my lap. I read it several times more, tracing my finger along the perforated edge. Mr Ellis’s work, I knew that now. Typed, most likely, on the BBC Micro in the town library, the Epson printer screeching away beside it. Whether I knew it all those years ago, I couldn’t say for sure. And yet, in some way, it was still my dad’s voice. Not the man who vanished, who never really contacted us again, but the father I’d imagined, needed, built from a dandy, a rope light and an old radio. Someone who cared enough about me to write across time.

I leaned back and looked around the shed. Cobwebs in the corners, the workbench damp and mildewed. Dried out paint cans. A children’s paddling pool. I remembered lying on the shed floor as a boy, safety glasses skewed on my forehead, believing with everything that the past was fixable.

I sighed and closed my eyes. Thirty-five years. And I was older than my father had been when he vanished. At a fork in the timeline now – Jenny’s affair had torn a rift. I hadn’t shouted, hadn’t thrown anything, hadn’t even asked for more details. Just moved to the sofa, cold and mute.

But now what? Smash it all? Ruin my family’s happiness the way my own father had done? And for what? So that in twenty or thirty years I could look at my ageing ex-wife in a Tesco queue and feel what? Vindicated?

Or would I feel ashamed?

I imagined it: seeing her by chance – a grandmother now, practical coat and thick glasses, her trolley filled with ready meals and cheap Chardonnay, grandchildren clamouring for sweets while she fumbled with the Clubcard app. And I’d remember being so consumed with jealousy for this ordinary, tired old woman that I’d wrecked the lives of our children. And why? Because, for a moment, she hadn’t been mine alone. In the great sweep of time, it seemed almost absurd.

I rubbed my hands together. Time was vast. Jealousy burned hot but left only smoking debris. A marriage – God, a family – was hard, slow work. Layered. Accidental. Precious. Do you fix a crack in the wall you have built stone by stone, or do you take a sledgehammer to it?

I glanced at my wrist. The old Rotary ticked on, its numbers faintly glowing in the shed’s low light. I will fix it, I decided. While there’s still time.

Outside, the garden was silvered in frost. A light snow had begun to fall, dusting the shed roof and the boundary fence. The kitchen glowed faintly ahead – its windows warm and strung with pretty fairy lights, the muffled sounds of family life inside, the faint smell of gingerbread lingering from afternoon baking with Finn. Jenny would be upstairs, the kids wide awake, bouncing with pre-Christmas energy.

I stood, folded the letter slowly, and slid it back inside the tattered paperback, putting it back in the box with the remnants of my childhood. I paused before I left the shed, placing a hand on the workbench, where rust bloomed in the corners of the old vice. As a boy, I’d believed the impossible in this place. Now, older and heavier, I found myself believing in something harder: forgiveness.

I padded upstairs, the carpet soft beneath my socks. The bedroom door was ajar. Inside, Jenny was sitting on the edge of the bed in one of my old hoodies, sleeves pulled down over her hands, staring at a cushion in her lap.

She looked up when I stepped in.

We stared at each other for a long moment. There was no anger in her face. Just the hollow look of someone waiting for judgement.

‘I thought you’d gone,’ she said quietly, pressing her thumbs into the cushion.

I stepped into the room but didn’t sit. I glanced at the bedside table – her phone face down, her novelty wine glass, mostly full, and a framed photo of us in the garden five summers ago: Mum in her final weeks, but smiling in the sun, the sky a brilliant blue behind her. Finn was barely more than a toddler, looking at the flowers instead of the camera, Gracey still a bump beneath Jenny’s maternity dress.

‘I was in the shed.’

She gave a dry smile. ‘Still building time machines?’

I exhaled through my nose, close to a laugh. ‘Something like that.’

She looked down at her hands again. ‘I think I could do with one of those,’ she said, her voice low and taut with weariness. ‘Go back and…’ She twisted the hem of her sleeve. ‘And not make such a bloody mess of everything.’

A silence opened between us. Not cold this time, just waiting.

I let my eyes rest on the photo for a moment longer, then slowly blinked and took a breath. ‘I stood at a fork in the timeline,’ I said quietly. ‘And I nearly took the wrong turn.’

Jenny looked up, and something in her face shifted, as if bracing for the door to slam.

I met her eyes. ‘I’m staying.’

She blinked. ‘What?’

‘I’m not walking away. We’ll fix this. If you want to.’

‘Of course I want to. I never wanted to break us. I just got tired of feeling so… unseen. Like I was shrinking more every day.’

Tears sprang to her eyes – sudden, unexpected. She covered her mouth with one hand and let out an involuntary sob. ‘I don’t deserve—’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t want to do what my father did.’ I glanced toward the landing, as if expecting to hear small footsteps on the stairs. ‘I don’t want our kids building time machines.’

Jenny nodded, her shoulders shaking slightly. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she whispered.

I stepped forward and knelt in front of her. ‘So am I.’

She reached out and laid a hand on my cheek. I closed my eyes for a moment, feeling a wave of relief wash through me. Then I kissed her palm, soft and brief.

‘I need to go back down,’ I said, standing up. ‘They’re building something.’

She nodded again, wiping her face with her sleeve. ‘Go.’

In the living room, the Lego box had exploded across the rug and under the Christmas tree – half a castle, remnants of a farm, the Millennium Falcon and the bare bones of what used to be a submarine.

Gracey was sorting bricks by colour into neat little piles on the carpet. Finn was squinting at some instructions as if they were in another language. Dougal was snoring softly on the sofa.

The children looked up when I walked in, holding a plate of chocolate digestives.

‘Hey, Engineers,’ I said, crouching down. ‘Room for one more?’

‘Obviously,’ Finn said, shifting aside. ‘We’re trying to build a spaceship, but Gracey keeps turning it into a farm.’

‘It needs a barn,’ Gracey declared. ‘Or the cows will float off into space.’

I stroked the stubble on my upper lip. ‘We can’t have unsecured livestock in zero gravity. A bovine containment unit is essential to the operation.’

Gracey laughed and Finn rolled his eyes.

I sat cross-legged between them, wincing slightly at my knees. I picked up two yellow blocks and clicked them together. ‘I used to be quite good at this.’

Finn gave me a sideways look. ‘You’re still good.’

They kept building. For a long time, they didn’t talk. Just the sound of clicking bricks and the occasional mumble as Finn searched for the right piece. From the kitchen, I heard the kettle click on and begin to boil.

Outside, snow was still falling, feathering the garden. In the shed, the dust had settled again. And in the living room, I began building something with my children, one piece at a time. In a week, it would be Christmas again, and this time I would stay in the present – for all of it.

About the Author

John Barrett Lee is a Welsh writer of short fiction. His stories have been published on both sides of the Atlantic, and have been listed for various prizes, including the Historical Writers’ Association Dorothy Dunnett Award. His debut short story collection, Quiet Enough to Listen, was longlisted for the Cinnamon Press Literature Award. He has lived in Italy, Thailand, and Vietnam, and is now based in Ho Chi Minh City, where he works as an international school teacher.

Visit his website here, and find him on X at @johnbarrettlee.